This article was originally published in Domus 965 / January 2013

In the last three or four years, there has been exponential

growth in the number of experiments and projects designed

to bring concrete, in the form of furniture and objects, into the

home. Advances in concrete-related technology have supported

these experiments and fuelled the creativity of a small vanguard

of designers who have explored this material's potential. For

example, it can lose its surface porosity and become extremely

lightweight (the range of ultra high performance concrete is

constantly expanding), change appearance in complex mixtures

obtained through combinations with other materials, and merge

with a patented fabric that solidifies in 24 hours to be modelled

as desired.

Hence it did not come as a total surprise to see the

launch — in the latest edition of the Interieur biennial — of a

furniture collection created by Matali Crasset, a designer and

the art director of the French company Concrete by LCDA. While

on one hand it represents the latest manifestation of a design

process that was already underway, it also brings research

focused on "domestic concrete" into a global system that has

transformed the whole company, as well as highlighting the

entrepreneurial potential of a geographical area that does not

usually see design as an element that can add value. The path

that emerges is promising and could spark a manufacturing

revolution, as demonstrated by Matali Crasset's project for

Concrete by LCDA.

Taming concrete

The launch of three pieces in the new Concrete Collection represents the second stage in a global project undertaken by Matali Crasset with a small French company to bring concrete into the home. Might it be the first phase in a manufacturing revolution?

View Article details

- Loredana Mascheroni

- 06 February 2013

- Montreuil Juigné

Loredana Mascheroni: What were the beginnings of your collaboration with this

small company from the Maine-et-Loire region?

Matali Crasset: It started from a meeting with three young

entrepreneurs — Julien Gay, Julien and Valentin Delalande — who

in 2010 relaunched LCDA, a small concrete firm based in Montreuil

Juigné, near Angers. Specialised in the production of lightweight

concrete, they wanted to use the company's know-how and

apply it to new projects. Since becoming the art director of the

new Concrete by LCDA in 2011, I have pushed the company in a

contemporary direction and worked to create a global project that

will give it a new identity. The Concrete Collection that we recently

launched is the second step in a four-stage journey.

The first part of this transformation project was the

Concrete Fab, which was launched in the autumn of 2011.

I decided to start with the development of turnkey or

bespoke architectural solutions — wall panels, work surfaces

for the kitchen, basins and fireplaces — which would showcase

LCDA's eight years of research into high-performance fibre-reinforced

concrete. The patented Béton Lège® makes it possible

to circumvent the traditional problems of weight and porosity

that render the standard material unsuitable. On average, the

structures we have created are three times lighter than those

using traditional concrete composites, while specifically designed

processes applied to the surfaces make them stain and wear

resistant. A year after the launch of Concrete Fab, we became

the "editors" of the Concrete Collection, which is currently made

up of three pieces — a table, a lamp and a set of shelves — but

this will be broadened once we have included the work of other

designers who we want to involve in the project. The next two

stages are still under development. The Concrete Hub will be a

blog specialising in the development of the culture surrounding

concrete, and will feature interesting designs created in the past

(including in the field of art). The Concrete Lab, meanwhile, will

invite young professionals to explore new production processes

and come up with fresh ideas that could even be put into practice

at a distance — it will be a form of virtual workshop.

Of concrete's properties, which one do you appreciate

the most?

It's a material that lets you break the rules and do something

totally different. The whole history of architecture proves

this. You only have to think of the work of Tadao Ando or Oscar

Niemeyer to see how much freedom it can give you. Personally

I'm not interested in working towards small revolutions, but

in finding a new logic and bringing it into a different context.

Concrete is a very malleable material. It can seem easy to use, but

it requires a high level of technical skill. Precisely because you

can create any shape you want, thanks partly to the constantly

evolving technology, you need more "intentionality" to take it

in the desired direction: you have to make decisions and know

how to develop the culture of concrete to create a relationship

between the objects and the people who will use them.

With both the Fab and Collection projects, you've done

a lot of work on the finishing. You haven't hidden the "rawer"

or "more primitive" aspects of the material — in fact, this is

something you've brought to the fore.

With the initial Fab collection we wanted to set up a strong

link between architecture and interiors. The first Panbeton®

panels are closely tied to the first uses of concrete: the surfaces

preserve traces of the wooden boards that have been used as

formwork since the 17th century, and the colour is the standard

grey. We applied the same intuition to the three pieces in the

Concrete Collection, because we consider the connection with

concrete's original appearance as part of the design.

Do you believe the market is ready to welcome concrete

in the home, bypassing preconceptions around the weight and

quality of the finishing?

mc Currently you only find heavy monoblocs in interiors, but

the technology now makes it possible to escape this trend and

find another way. Let's take the three pieces in our Concrete

Collection. The table, which for me is the archetypal object for a

meeting place in a house, is large but light: the surface structure

has a honeycomb core covered by a 10-millimetre layer of high-performance

fibre-reinforced concrete. This design is made

possible by the Lightweight Concrete moulding system, which

allows it to weigh four times less than a traditional structure

while maintaining high mechanical resistance. To create a

conceptual link with large wooden tables in country houses, the

texture of the surface has visible traces of the wooden formwork,

but the resin finish makes it smooth to the touch.

The structure of the shelves is inspired by a tree, with the

branches supporting the books — it's like a spinal column for

knowledge. We used Ductal® here, a concrete with a high

percentage of synthetic fibres, which makes it particularly

resistant to traction and means it can be used in reduced

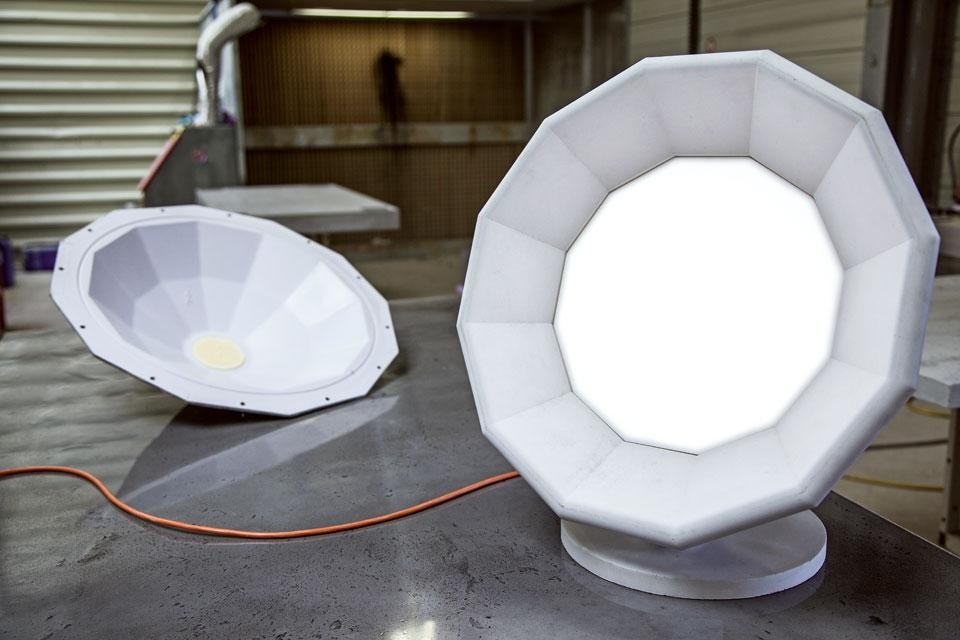

thicknesses. The shape of the lamp is borrowed from the sound

mirrors in Folkestone, England; it has an explicit connection with

a purely architectural object and plays with the change of scale.

In this case, the concrete finish is very fine-grained, which brings

out the design of the diffuser.

Has the choice to use concrete led to lower production

costs — and therefore lower prices?

That wasn't our aim. We wanted to create distinctive products,

not cheaper ones. The cost to the public is roughly the same as for

similar mid-range products made with more usual materials.

Is this because the technology you use is still in the

development phase?

That depends on the size of the company (there are 13 people

working for LCDA). Small-scale production structures have the

advantage, however, of being able to work well in terms of the

design and development of the company's know-how. Concrete

by LCDA is able to give this material a new sense of naturalness.

This enterprise reignites the issue of the relationship

between craftsmanship and industry. Is it necessary to focus

more on artisan work and limited-run series?

Both modes of production have their own spheres and

systems. All materials have both industrial and artisan

applications — with concrete at least, the industrial ones are often

not particularly innovative. We have probably gone too far down

the path of standardisation and uniformity. I'm convinced the

designer's task is to find a way of expressing the full potential

of a material. This is something I feel more strongly about and

it is achieved with diversification and research. We have to find

new approaches and help companies pursue them step by step in

accordance with their own characteristics and dimensions. Most

of all it's the small firms that allow you to work in these ways and

develop a global vision. I'm finding that the designer's task is not

simply to design new pieces, but also to show the way ahead.