In the last three or four years, there has been exponential growth in the number of experiments and projects designed to bring concrete, in the form of furniture and objects, into the home. Advances in concrete-related technology have supported these experiments and fuelled the creativity of a small vanguard of designers who have explored this material's potential. For example, it can lose its surface porosity and become extremely lightweight (the range of ultra high performance concrete is constantly expanding), change appearance in complex mixtures obtained through combinations with other materials, and merge with a patented fabric that solidifies in 24 hours to be modelled as desired.

Hence it did not come as a total surprise to see the launch — in the latest edition of the Interieur biennial — of a furniture collection created by Matali Crasset, a designer and the art director of the French company Concrete by LCDA. While on one hand it represents the latest manifestation of a design process that was already underway, it also brings research focused on "domestic concrete" into a global system that has transformed the whole company, as well as highlighting the entrepreneurial potential of a geographical area that does not usually see design as an element that can add value. The path that emerges is promising and could spark a manufacturing revolution, as demonstrated by Matali Crasset's project for Concrete by LCDA.

Matali Crasset: It started from a meeting with three young entrepreneurs — Julien Gay, Julien and Valentin Delalande — who in 2010 relaunched LCDA, a small concrete firm based in Montreuil Juigné, near Angers. Specialised in the production of lightweight concrete, they wanted to use the company's know-how and apply it to new projects. Since becoming the art director of the new Concrete by LCDA in 2011, I have pushed the company in a contemporary direction and worked to create a global project that will give it a new identity. The Concrete Collection that we recently launched is the second step in a four-stage journey.

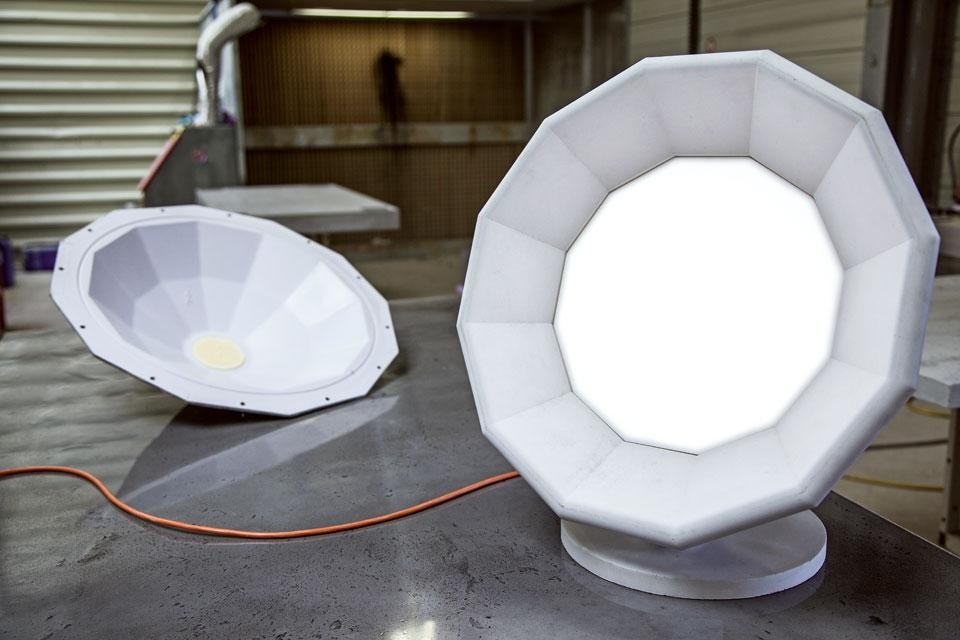

I decided to start with the development of turnkey or bespoke architectural solutions — wall panels, work surfaces for the kitchen, basins and fireplaces — which would showcase LCDA's eight years of research into high-performance fibre-reinforced concrete. The patented Béton Lège® makes it possible to circumvent the traditional problems of weight and porosity that render the standard material unsuitable. On average, the structures we have created are three times lighter than those using traditional concrete composites, while specifically designed processes applied to the surfaces make them stain and wear resistant. A year after the launch of Concrete Fab, we became the "editors" of the Concrete Collection, which is currently made up of three pieces — a table, a lamp and a set of shelves — but this will be broadened once we have included the work of other designers who we want to involve in the project. The next two stages are still under development. The Concrete Hub will be a blog specialising in the development of the culture surrounding concrete, and will feature interesting designs created in the past (including in the field of art). The Concrete Lab, meanwhile, will invite young professionals to explore new production processes and come up with fresh ideas that could even be put into practice at a distance — it will be a form of virtual workshop.

It's a material that lets you break the rules and do something totally different. The whole history of architecture proves this. You only have to think of the work of Tadao Ando or Oscar Niemeyer to see how much freedom it can give you. Personally I'm not interested in working towards small revolutions, but in finding a new logic and bringing it into a different context. Concrete is a very malleable material. It can seem easy to use, but it requires a high level of technical skill. Precisely because you can create any shape you want, thanks partly to the constantly evolving technology, you need more "intentionality" to take it in the desired direction: you have to make decisions and know how to develop the culture of concrete to create a relationship between the objects and the people who will use them.

With the initial Fab collection we wanted to set up a strong link between architecture and interiors. The first Panbeton® panels are closely tied to the first uses of concrete: the surfaces preserve traces of the wooden boards that have been used as formwork since the 17th century, and the colour is the standard grey. We applied the same intuition to the three pieces in the Concrete Collection, because we consider the connection with concrete's original appearance as part of the design.

mc Currently you only find heavy monoblocs in interiors, but the technology now makes it possible to escape this trend and find another way. Let's take the three pieces in our Concrete Collection. The table, which for me is the archetypal object for a meeting place in a house, is large but light: the surface structure has a honeycomb core covered by a 10-millimetre layer of high-performance fibre-reinforced concrete. This design is made possible by the Lightweight Concrete moulding system, which allows it to weigh four times less than a traditional structure while maintaining high mechanical resistance. To create a conceptual link with large wooden tables in country houses, the texture of the surface has visible traces of the wooden formwork, but the resin finish makes it smooth to the touch.

Has the choice to use concrete led to lower production costs — and therefore lower prices?

That wasn't our aim. We wanted to create distinctive products, not cheaper ones. The cost to the public is roughly the same as for similar mid-range products made with more usual materials.

Is this because the technology you use is still in the development phase?

That depends on the size of the company (there are 13 people working for LCDA). Small-scale production structures have the advantage, however, of being able to work well in terms of the design and development of the company's know-how. Concrete by LCDA is able to give this material a new sense of naturalness.

Both modes of production have their own spheres and systems. All materials have both industrial and artisan applications — with concrete at least, the industrial ones are often not particularly innovative. We have probably gone too far down the path of standardisation and uniformity. I'm convinced the designer's task is to find a way of expressing the full potential of a material. This is something I feel more strongly about and it is achieved with diversification and research. We have to find new approaches and help companies pursue them step by step in accordance with their own characteristics and dimensions. Most of all it's the small firms that allow you to work in these ways and develop a global vision. I'm finding that the designer's task is not simply to design new pieces, but also to show the way ahead.

Tailored furniture shapes an apartment in Cremona

For a design that focuses on both functionality and aesthetic care, the furniture created with Caccaro systems can meet all needs and define new concepts of space.