So begins Alberto Alessi’s familiar story about the debut of his gastronomic and design dealings with Alberto Gozzi and Richard Sapper. Richard was the gifted man who almost 30 years ago, when interviewed by Any Pansera on the nature of his work, came out with the fantastic statement: “I think a designer must explain himself through his work, not through verbal explanations. I therefore have nothing to say about my work in general.” A long time has passed since that incisive definition of a complicated profession, where “fine words are not true, and true words are not fine”. Things get more complicated when the profession then has to be applied to the rituals of food preparation, to the inexplicable hours, sometimes days of toil that culminate in the seven or eight minutes needed to assimilate just enough to keep hearts, brains, kidneys and other organs ticking over for a while, until the next repetition of the same rite.

If then we add the perversion of wishing to handle diabolical kitchen utensils, such as razor-sharp knives, to the pleasurable risk of preparing any dish less humdrum than spaghetti with tomato and basil sauce, then it seems indispensable to triple the level of intelligence and reassemble the Alessi-Gozzi-Sapper trio, who recently set about integrating that same Cintura d’Orione series. Connoisseurs will already be acquainted with the first and third figures. But the second – who does not win Compasso d’Oro prizes or smile on the covers of Capital, and is not a Made-in-Italy icon – has always stayed out of the limelight and kept a distinctly Piedmontese low profile. To my mind, this gives him the air of a kind of guru, sitting cross-legged on the hilltops around Lake Orta ready to send secret dispatches of chemico-mathematical formulas to Alberto Alessi, as he wrestles below with the stubborn Sapper and his indisputable certainties.

When left at his ease, though, and in charge of slicing, filleting and tearing the flesh off hams, steaks and the like, Gozzi turns out to be an affable conversationalist and cultivated maestro, a homme du monde who is not afraid to argue on equal footing with an industrialist and a designer rightly enshrined in today’s industrial mythology. But the early days can’t have been easy for him either. “I always remember what Dr Alberto told me: ‘I need to know the dimensions! Remember, we’ve got to make the prototypes (which in those days were made by hand), and every prototype is very expensive so we can’t afford to make mistakes…’ He was very severe!”

Alessi’s severity was certainly justified by the investment involved, but also by the risk which he, still a young entrepreneur, had taken to transform the family business’s products from wares for consuming food into the instruments for its preparation. However, the guidance received from Gozzi, who had grown up in the old school of high-class Italian hotel cuisine, was in itself “heretical”. Gozzi’s passion for cooking is absolute. He clashed with chefs because he didn’t want to shut himself in the kitchen. He tried to be present in the dining room too, in direct contact with guests who had to choose and sample his dishes. But here again he would be frowned upon by the maître d’hôtel, who was not at all pleased by the appearance of this young fellow, however capable, and a cook to boot, who by hierarchy and tradition might at best be permitted to rule over the kitchens. In a sense, this anarchic stance represented the archetype of the true gourmet: an enthusiast to be sure, but nevertheless capable of following his food “from the cradle to the grave”, in its life cycle from the field – or breeder – to the set table.

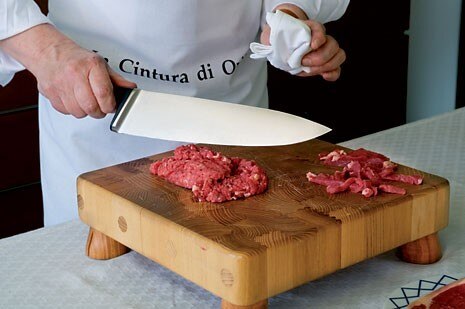

Besides being an industrialist, at heart Alberto Alessi is also a homme du monde culinaire. For some time he has been cultivating his own vineyard (around the new house above the lake, designed by his great friend Alessandro Mendini and where he will sooner or later be living). Together we tasted its first wine in the precocious spring of this year. In this photo-cinematographic sequence by Mario Ermoli, Alberto stands pretty much aside, now certain that the instruments, designed by Sapper and developed with Gozzi to cut anything destined to be eaten, are in perfect shape. Yet he still seems to show signs of curiosity, to see if this time Gozzi will once again recognise himself in these instruments of his, these genuine branches (rather than prostheses) of the body and of the intelligence of the “General Manager of Table and Kitchen Sectors to the President of the Italian Republic”.

Gozzi treats the cooking materials like a tailor’s tools, injecting them with new life and physiognomy, however ephemeral, while deftly handling the carving knife or fruit-peeler. Dreamily he reminisces on the prehistory of modern cuisine, when a single knife (the carving knife of course, his favourite) could be used to prepare, serve and even to eat meat). But he quickly recovers, and almost flirtatiously exalts the ergonomic qualities of his knives’ handles. Certainly they are just right, and absolutely safe, in the delicate hands of the ladies who, from kitchen to table, want to be able to do everything nicely.