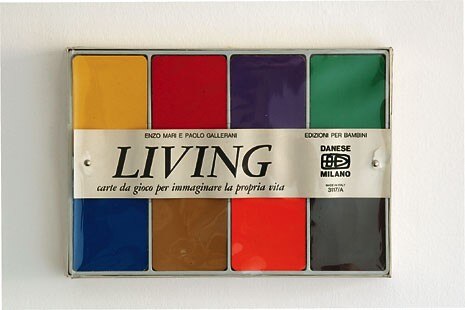

Where can a boxer married to a terrorist live? What does a female cook who lives with a retired general in the Rocky Mountains want? What are the aspirations of a bachelor barber, who likes to travel by caravan? Bizarre combinations are, of course, a part of life. And yet, as a rule, we spend our lives trying to keep those combinations under control. In our work we continue to construct neat and tidy, congruous classes and relationships, where everything fits into an immediate logic: a rich surgeon (with lover) lives with his wife in a large house full of fine paintings, whereas a young immigrant who owns nothing lives in the disused sheds of an ugly suburb. Nevertheless, the lives that we study, the lives whose spaces we architects and designers design, remain tremendously far from our typologies; they couldn’t care less about our efforts to standardise them. Enzo Mari’s card game seems to tell us that our cities do not accommodate “types” of living, but infinite combinations of practices and feelings, each different to the other and all absolutely logical if we bother to understand them. It shows us that our classifications are only feasible if we know how to dismantle and reassemble them all the time, without ever treating them as real substitutes for life itself. Enzo Mari seems to be saying that to discover the unpredictable combinations of daily life and its spaces, we need the systematic rigour of an outlook which, by accepting chance, can dig out the unforeseeable. But that is the point: to get closer to the infinite variety of the world outside we need rigour, a method, and precise rules. Like those of a card game. S.B.

Letter to Pier Carlo Palermo, Dean of the Milan Polytechnic’s Faculty of Architecture and Society

The reference is the children’s game called “Living”. In a totally aleatory form, this game determines the environmental, human, psychological and non-institutional premisses that every student must tackle in order to broaden and improve the quality of their design horizon. The aim is to encourage these young people to rediscover Architecture as ART (which, after all, is what it really is): where techniques remain necessary tools and economic and socio-cultural aspects are not values but pollutant conditioning factors to be dealt with by decreasing their negative gradients. The significance of architecture’s great historical archetypes, and the acquisition of the principles of practice/theory (the exercise proposed), are the propaedeutic factors in the Art of Architecture. Practical mastery only exists if doubts are cast on its every manifestation by modelling multiple alternative hypotheses. The cost of myriad modellings can be tolerated by regaining the manual capacity to represent: corresponding to the stream of thought which is far more potent (as is evident from our phylogenic evolution) than the rickety electronic contraptions that are today so invasive and unsuited to the process of designing.

Enzo Mari, Milan, June 2006

Mari the game master, wizard and a game sequence

Francesco Librizzi

On a Friday morning, Enzo Mari enters a classroom at Milan Polytechnic to initiate an experiment with the students. The project is called “Living: Playing Cards to Imagine Your Life”. He conceived this children’s game 30 years ago, but today Mari hasn’t come to play. With his 80 playing cards, he’s here to communicate a clear and definitive message to everybody who will take part in the game: in our destiny as designers, we will have no choice but to expose ourselves, in our designs, to the multiplicity of circumstances. So for now, he is the creator of the circumstances, with eight decks of cards. The session starts with a few jokes by Mari the sneaky, and then a few aphorisms by Mari the wise. Now that his sculptural unit of eyebrows-beard-hair is charged with expressive energy, the ritual begins. Mari takes the decks of cards out of a box and puts them down in order before him. Then he takes the cards in his hands and calls the students one by one, almost as if giving Holy Communion. He draws the sequence of cards: “Antonio, you’re a mechanic, your wife is a…” In a sacred atmosphere that is not without irony, we watch the staged evocation of each participant’s new identity. The game we are undertaking will last for some time, and could make or break us. It will force us to choose, remember and come to conclusions – a form of training. So we find ourselves confronted by these picture-less cards, with only a colour on the back of each deck and a word on each card. They are plain because drawings always imply that a design has already been made. The game will compel us to tell our new story and establish a relationship between the things that fate and the cards have assigned us. We begin to devise alternative solutions along these guidelines. Our search involves trying all possible solutions of this multiple-result puzzle. Practice and theory. The “Me” facing all the rest. “Do you want to know what I would do in your place?” It’s the only large interface that this elderly student, as he likes to call himself, creates between the younger students and himself.

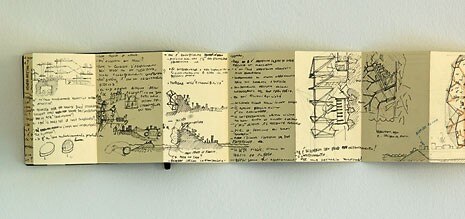

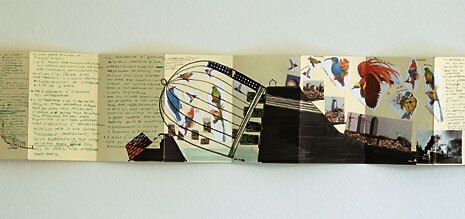

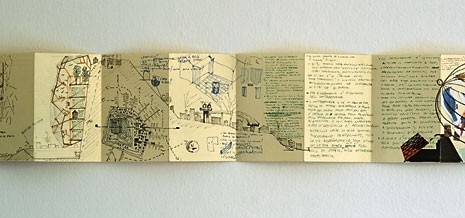

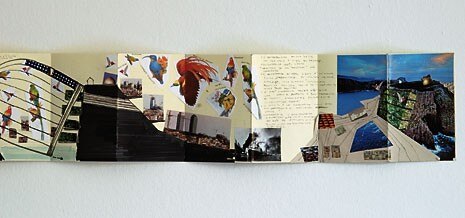

Designing in cursive

Computers are banned. The students playing the game go by the rules of the magister ludi. In truth, drawing by hand is the most immediate and succinct method that a designer has at his disposal. The ability to draw rapidly saves time in laying out a maximum number of combinations and alternative models. The students’ first drawings are rather infantile sketches. Many draw portraits of their story’s protagonists: the boxer with a black eye, the smuggler with a black mask. Graphic signs with an almost superficial iconography. Perhaps it would be useful to grow fond of one’s alter-ego character-client. With fairly rapid progress, the hidden architects steadily begin to surface: a boxer means a ring, a smuggler means a clandestine market, specific merchandise, an area to move around in stealthily and a hideout with specific qualities. This means designing in cursive, and if necessary, even using shorthand. Much practice is needed. At first everyone is truly caught unprepared, but they are equally motivated to try and recover their ability to portray their own ideas. “I think that the students were surprised by their work and by their abilities. After a moment of desperate impasse when they realised they would not be able to use a computer, they timidly got involved, and the identity of the characters became a very personal, even intimate issue. I think this is where Mari really hit the bull’s eye!” (F.V.)

“You’re all castrated”

No rules. No real limits. No designated territory. Only the code of the cards. The game only has limits that are connected to each other. Who are you, what do you do, with whom and in what situation are you involved? You just need to take into account all the variables, without any exceptions. For once, try to think that your environment is your wizard neighbour’s life, instead of Milan and its building regulations. For once, places, history and the plans that are based on them are not part of the project’s conditions. That might seem like an immense facilitation. But the point of greatest dispersion is the inability to design something without knowing WHERE. Maybe the students are too used to structure, a symptom of a kind of school that is based on rules and shielded by science. A school that gives you prêt-à-porter norms rather than flexible instruments. This is where Mari’s invective against a certain part of the academic world has its origins, which he blames for not producing real tools of knowledge, but stumbling through it, creating generations of un-free thinkers, “castrated” by their own thought. So how does Mari think a young person should be trained? Confronting the universe alone to choose and create models of logic, basing themselves purely on the discipline of their own reasoning? Everyone’s guide, he answers, can only be the great masterpieces of art and architecture. Not the masters themselves, but their best works. Those are the pieces that have survived the test of time, that are still here beyond the contradictions of their own times, beyond the human misery of their creators and commissioners. Mari is speaking substantially of the inevitability of art to create monuments where fullness of meaning totally coincides with its representation. Great works of art, says Mari, are the only possible realisation of ethical dictates. It is the form given to values of all humankind. “This is Mari’s message pertaining to the relationship between ethics and form: form as the medium of ethics; ethics as the fundamental motivation for form; form as the inescapable possibility for the designer to act ethically in the world. This is the most political and radical side of his teaching – almost revolutionary if considered in the contemporary context.” (C.P.)

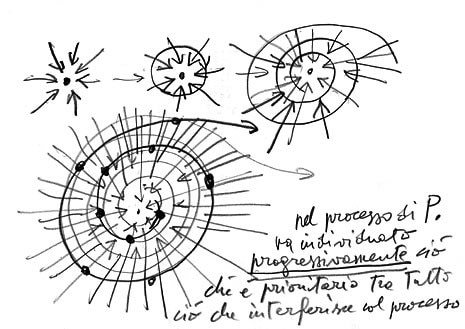

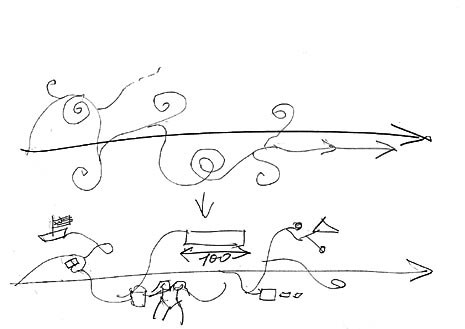

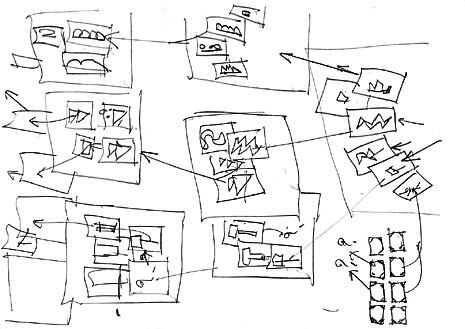

Art, science and two chimpanzees

Mari bases his reasoning on an extremely close relationship between alternatives and solutions. He gathers the data very scrupulously. He starts to create relationships between the components in many directions. He discards the variables that he considers superfluous and gives shape to the most significant combinations. Then he places everything in front of himself. He never draws in bound notebooks, only on loose sheets of paper that can be displayed simultaneously to create a macro design of the progress in his thinking. Here is where the most fascinating, but also the most ambiguous part of Mari’s process comes into play: the relationship between art and science. How can a train of thought based on the “necessity” of chosen and discarded solutions, on the unambiguous convergence from multiple to simple, from “redundancy” to “monument”, be based on the entirely arbitrary decisions of the artist? What guarantee is there that those decisions are the “right” ones? Mari illustrates his science paradigm. Knowledge that is based on specific research, that is accumulated in a linear way, where the applied method is documented, can be shown and therefore recognised universally. Scientific discoveries truly represent an objective basis for knowledge. Science as the only fully democratic form of knowledge. Mari is not indifferent to the attraction of this marvellous objectivity. He always sets up his reasoning in a scientific way – at any rate as rigorously as possible – because the knowledge that the artist is called upon to face is not specific, but total: it is impossible to pursue in objective terms. The cognitive route starts to be interspersed with arbitrary decisions, with an absolute “yes” and “no” that cannot be immediately accepted by everybody. These are solutions that instantaneously become subjective, and will demonstrate their value, the validity of their form, in centuries to come. In order to explain what art is, or rather how it can be recognised, Mari tells us an anecdote. It is the story of a naturalist who was in Africa for some time studying a group of chimpanzees. It tells of her first endeavours to gain acceptance from the forest-bound community, their first exchanges, the reciprocal recognition of belonging to species that are different, yet so similar as to seem a metaphor of each other. After a while the researcher noticed that every evening two young chimpanzees had the habit of leaving their shelter of trees, only returning a few hours later. Intrigued by the regularity of this occurrence, the scientist decided to follow the two in secret to discover what they were doing during their absence. Trying not to lose sight of them in the dense forest, after a long walk she arrived at the place of discovery. The two chimpanzees were sitting on the crest of a hill with the forest stretching out below them. They were watching that enormous fireball, the setting sun. As they watched, they embraced. That, says Mari, is art. Francesco Librizzi

Technology meets aesthetics, with Cordivari

With their rhythmically textured external surfaces, the Run and Seven Lines fan coils become natural elements in the landscape of contemporary interiors.