Reasons for an encounter

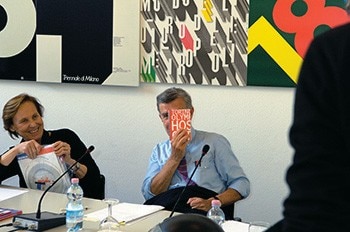

A Italo Lupi. Ever since Stefano Boeri became editor of Domus, whenever we came across each other in various situations we always said we should do something together. The Furniture Fair seemed like a good occasion to bring the two editorial teams together, not in a panel discussion because that isn’t what it is, but rather in a kind of joint meeting, as if everyone were on their home ground discussing issues not strictly linked to design but that open onto various territories. I think this meeting is a unique opportunity, a great demonstration of anti-conformism and openmindedness.

d Stefano Boeri. It is also a great pleasure for us to organise this unprecedented encounter that, beyond the theme we will be addressing today, I hope can become a regular event. The meeting of two Milanese editorial teams, linked to competing publishers but sharing the same free curiousity and obsessions, could generate moments of great interest and tension. There it is also more that this: the fact that two places for intellectual output such as Abitare and Domus meet and talk to each other is also an important sign. It goes against the grain in a city like Milan which is made up of separate and distinct islands of excellence. There is no communication between places where research is carried out, even if they operate in the same field. So this is a very good step.

The April issue

d Stefano Boeri. In the April issue of Domus we decided to try and look at the design of complex objects from three main perspectives. The first regards the communicative disposition of design, with its capacity to add value to products and company brands in terms of symbol and identity – also thanks to the name of the designers. The second weighs up a sphere that is still closely linked to production, to the functional and aesthetic refining of mass-produced everyday objects. The third perspective sees design as a form of survival, where product design and everyday objects emerge from self-organised communities of user-designers.

A Italo Lupi. I looked at this issue of Domus with great admiration. It is a very different issue from your usual ones because it seems to put forward a highly original slant on things that is organised very clearly. Instead we put together an issue with an approach that is not so very different from our usual one. It is not specifically dedicated to the Furniture Fair but includes pages on design that indicate some preferences. Abitare makes strong judgements, in the sense that it chooses a number of things and presents them, implying a positive judgement. This issue also includes a theme held dear to the magazine, that of recollection, taking another look at personalities – in this case Roberto Poggi – who have been influential in different fields, both in design and in architecture. We are among the few who still remember not just the great masters but also the great craftsman in this field.

d Joseph Grima. In this issue we decided to look behind the object, understand how it got where it is. Also for this reason, the various chapters start with the coordinates of “GoogleEarth”, something that amongst other things relates us to new ways of looking at space from a distance. The tagline of Domus is “Architecture, design, art and information”: in this issue we explored the complex relationships between the identity of objects in the “communicative” sphere of design and the geographical aspects of their production.

d Francesco Librizzi. Looking at design from within creates a kind of greenhouse effect, an overheating of these “icebergs” that are melting and that show an absence of innovation, of truly new products. With the April issue, by taking up some ideas expressed by Paul Virilio, Domus attempted to widen the attention focussed on the space in which design products are manufactured and consumed, to include also the time in which they are simultaneously shared. Speaking not just about objects, but about the events that have determined them, of how a number processes act simultaneously on the real world. I think that it is a good observation point for a magazine that is aimed mainly at creators of design: to talk about new strategies, tools, rather than continue to broaden the reportory of images.

Communicating design

d Mario Piazza. Issue after issue, we address the problem of how to present design in Domus. The April issue was deliberately strongly systematic and posed a general question: what cognitive tools can we use to examine design today, or rather the phenomena of geodesign. It is evident that specialised critical approaches are increasingly insufficient. New interpretative stimuli are needed that in our opinion can be developed by crossbreeding multidisciplinary instruments (aesthetics, sociology, economy, etc.) and multi-modal feedback. You can no longer interpret design if you don’t make the effort to introduce and engage different disciplines. But one also needs to be able to formalise these interpretations and investigations with multiple narrative models, in fact one needs to “navigate” across the various forms of media. This approach is increasingly necessary because the authorship model in geodesign is a marginal phenomenon. Works (objects with a name) will disappear or be increasingly mixed (fluid hybrids), and perhaps with them also the authors. Behind this rough scenario is a broader issue of how to understand the problems of design, its languages and its specificity. In the April issue the three categories served to organise “a possible catalogue” of the design phenomenon. There was a certain unusual freedom in the selection, almost a random sampling that sustained the arguments behind our hypotheses but that necessarily could not be set down with great refinement. Hidden behind “design for communicating, producing and surviving” lie possibilities for interpreting the organisational processes of design, the forms with which innovations and experimentation are developed, the ways in which compositional and linguistic tools cross over, and the strategies with which expression is translated. All this occurs through fluxes, exchanges and interactions that make the things we use fluid and mobile. For example, “design for survival” is not just a category in the moral and ethical sense of designing but also the representation of the language that expresses this category. So we can find this category in other situations (also far away), like those of the “mature” design companies. I think of Vitra who are using forms, styles and expressions with a third world bricoleur aesthetic. In reality our effort, and perhaps that of the magazines, should spur the debate on cognitive instruments before issues regarding the form of objects. The safeguarding of the territory of design, the object and its use is one of the bastions that Abitare has always upheld. Our magazine seeks to acknowledge different interpretations, looking between the folds and at other sides, and it does so with an approach similar to that of a film director, interpolating different forms of narration and writing. It is a challenge for the future.

d Loredana Mascheroni. It seems symbolic to me the decision to talk about objects addressing the themes that surround them. The cover of the issue we presented last year during the Furniture Fair showed Philippe Starck’s much-debated lamp in the form of a rifle. At the time we asked ourselves what were we trying to achieve if we were associating with this object in some way. The answer was that we wanted to talk about the morality of design. We did something very risky, that has definitely attracted controversy on the part of those in the information field as well as the producers. This attitude, that could be considered presumptuous, seems to me to exemplify our peculiar way of talking about design and its world, our desire to stimulate debate, to sensitise and consequently generate change.

d Marco Belpoliti. It would be interesting to try and take your magazines out of their field. For whom does one write? For what kind of reader? For one’s colleagues, living and dead? For scholars? This is a very important ethical aspect. Very often design and architecture magazines are in jargon. I have sometimes photocopied articles and had my students read them. The response is interesting. Often they are absolutely incomprehensible, not because of the terminology but in the prose, the rhythm, the syntactic construction of the phrases. At times they don’t seem to have grammatical subjects not because they are incorrect but because the subject seems hidden, absent. They are written in architect-speak.

Design, the everyday and the exceptional

A Marco Romanelli. Stefano Boeri said: dispositions towards communication, production and survival. I have to say that I have a conception of design that is far closer to the everyday than the exceptional. The words of Giulio Carlo Argan come to mind when he said that design seems to have become “the popular art of the new millenium”. Unfortunately the current situation brings one to say that Argan is wrong, although he sends out an extraordinary message of hope. In this sense visiting the Fair didn’t give me any confirmations. If we think about everyday design we should think about the objects and in reality, statistically, at the last Furniture Fair the list of objects that brought the design process to a happy conclusion was even shorter than in previous years. What has taken the place of “design as an object” or “design as a communication system”?

A Fulvio Irace. Going back to the word “exceptionality”, some distinctions need to be made. There is exceptionality that etymologically speaking is something that is an exception to the rule and there is exceptionality in a media sense, which is perhaps what Marco Romanelli meant. Exceptionality as a departure from the norm is an intrinsic notion in design history. Modernism is rich in exceptional objects from this point of view (what is more exceptional than the Maison de Verre by Pierre Chareau, an object that is absolutely outside the norm?). Modernist culture asked itself whether the exceptionality of the object is proof of scarce morality, scarce sensibility to themes of environmental democracy, or if instead one can capture something positive in exceptionality related to the experimentation of a prototype. To take a contemporary example, the chairs by Ron Arad on show at Metropol seemed a very interesting project, even though they certainly cannot satisfy the criteria of democracy that I mentioned before. But I think that it would be moralism, therefore not true morality, to deny the lawfulness of carrying out an operation that is extravagant yet, in my opinion, rich in contents intrinsic to the morality of the designer who has to experiment with new things and their own creativity.

A Marco Romanelli. Many companies, who I imagine are a bit scared, have responded to a not easily comprehensible market with a system of objects that work on team spirit rather that on excellence. Very often the pieces at the Fair are catwalk pieces that no longer function with respect to interior design. For myself and for us at Abitare this link between design and interior architecture is one of the fundamentally Italian scenarios. Design should be experienced and evaluated within architecture, with a continual exchange of skills and scale between one field and another.

Concepts are disappearing

A Marco Romanelli. Mario Piazza said that works and authors are disappearing. In reality, I think it’s the concepts that are disappearing. In design there is a process at the mountaintops, and you at Domus have talked about this; and there is a process down in the valleys, the piece of furniture that comes out of a showroom and enters a house, and we at Abitare almost always try to talk about that. But the basic problem is that there have been periods when objects told stories and expressed concepts.

A Fulvio Irace. This lack of concepts may perhaps signify that the design we are talking about has lost the central role that it had in previous decades. And that probably the way that we are describing it is a bit mythological, one hears the same names repeated like a kind of postmodern Homer describing an Olympus in which there are courageous captians, femmes fatales, braggarts, great masters. It is a kind of circular world where each year you get together, take a look, assess the losses or gains in terms of the objects’ quality, and take stock of things. One needs to ask if the Milan Furniture Fair is design or part of a wider phenomenon, if what we are talking about is a very showy piece – with all its theatrical connotations in the exceptional concentration of a big party – within a larger, more evasive and not necessarily better system. There is also a strong media and advertising component, self promotional and capitalist that perhaps one should decide to consider with a bit of cynical realism, without being amazed every time. There are very heavy moments of crisis, such as the changing nature of the entrepreneurs. But is the fact that the entrepreneurs have changed, that they are no longer those who founded design in the 1950s, a generational fact, does it belong to a biological destiny of humanity? Or has there been a change in the nature of the entrepreneur and as a result also that of the author and the notion itself of the use of the object in a cultural sense? I ask myself what position needs to be taken to try and redefine these questions that we are discussing in a fairly unanimous way, to at least try to define a logical picture that helps us to understand them better.

A Beppe Finessi. It is evident that ours is a world made up of a few people and very few things, very few numbers, a microcosm with respect to reality; it is obvious that we deal with a few things made by us and for us. But if we start to shift the point of view, something that is very interesting, we should adopt new and shrewd means and companions, because there’s nothing more embarassing than reading – not in our magazines, it goes without saying – opinions on the Furniture Fair, or on what we deal with everyday, expressed by people not just a long way from this world, something that is positive, but without any kind of critical faculty. I don’t mean “if one doesn’t operate a remote control” but if we don’t at least construct with these new interlocutors some kind of “instruction”, the resulting judgement on our world are usually utterly senseless. If any of these “experts” were taken to the Fair, they would appreciate things that for us are unpublishable, uncultured, ugly, heavy.

A Marco Romanelli. Before I said that today the concepts have disappeared and therefore all of us have to make more effort, because in reality we are striving for the impossible. There isn’t a strong heart anymore, no strong emotion to defend or take forward, no flag to hold high; it’s all more difficult. When we were at Domus in 1986, the concepts were very strong, very violent and very violently expressed. For us there was the struggle of the postmodern, so it was all much easier.

The manufacturers

A Beppe Finessi. It seems to me that the manufacturers are the problem, in other words the businesspeople. Apart from some exceptional cases, many manufacturers no longer exist, or have changed their objectives. Many have levelled off, maybe upwards, but they have become homologated and today have a duller image. Then there is the problem of the passage of generations. The companies that made history in this strange world of design – not just Italian but very Italian – have inevitably arrived at a generational transition. The problem is also that in this change something else has happened. The “small scale” system functioned according to set rules up to a certain size and turnover. Those companies functioned well because they were small; they could afford not to know about marketing and advertising, in other words basing things on an attitude of intuition, healthy pragmatism and freedom. That was their strength and today this is no longer possible. Perhaps the market today talks of other numbers and other things, whilst we continue to seek an exceptionality that is the fruit of creativity, of applied intellegence, of skill and we look through eyes that are inevitably focussed on the small. Seeing the manufacturer of sanitaryware that makes 4 million pieces published, one is aware that the perspectives have been completely turned upside down. I have had the opportunity to talk to a number of new businessmen who have taken the baton from their fathers, often with good commercial results. Between the lines it is evident that their aim is to maintain the company for a few years and then sell it. In April we published an article on Poggi, a company that would rather close down than be bought out. However, this is an extreme that represents an awareness and pride on the part of the entrepreneur who founded it, of “being” the company. Instead these new industrial captains often deal with one reality in the same way they would deal with any other. Which brings us to one of the points – there will always be a Chinese company able to buy IBM, there will always be a bigger company that one day will find perfect containers, not so difficult to manage exactly because they are administrated with criteria of high finance, and therefore easily acquirible. The legendary furniture companies would never be sold in these conditions, in the sense that noone would know how to manage them.

Design as a mass phenomenon

D Francesco Librizzi. It seems that design is already a phenomenon of the masses. There are manufacturers today aware of the fact that there is already a public to whom to sell a mass of “designer” objects. Never like this year have I seen such incredible design tourism around the Fair: there were hundreds of thousands of people, an enormous proliferations of spectators but also of “minor authors”. Perhaps on this planet eyes more attentive than ours exist with regards to the phenomenon of design.

A Marco Romanelli. Design is a phenomenon of the masses, in which the masses are generally not educated. I don’t think it is true that the Fair is not as important at the moment as we from inside are judging. It is still a crucial moment. We can gather this from the quantity of totally incompetent articles published even in the higher quality press, where something is pushed as design that has nothing to do with our research categories or control of aesthetics and form. In reality design became a mass phenomenon after the bombardment by scarcely expert people. In this sense it is very serious to have completely abandoned a consideration of the educational problem within schools. How can we think that future generations will be able to deal with increasingly complex and crushing mechanisms if they can’t enjoy a basic education?

SaloneSatellite

d Maria Cristina Tommasini. I liked SaloneSatellite very much this year and I found a variety of interesting and beautiful things. This slightly seems to contradict what was said earlier about there no longer being any education. Perhaps there is good education abroad, and a bit less so in Italy.

A Beppe Finessi. I agree and I also think that this was the best SaloneSatellite for some years. The new space, although it was less showy and imposing than the one used in the past, was also better structured, more organised and worked very well. The young foreign designers were certainly at a high level whereas the situation of the Italians was a bit embarrassing. The better Italians probably don’t need to come to the Satellite because 90% of the things are here around them. Perhaps everyone’s antennas, even our own, are ready to register the first positive results and therefore contacts are made immediately. Meanwhile the foreigners continue to consider the Satellite as the first and only real possibility to come to Milan. The problem of the schools also certainly exists. One notices schools of extraordinary quality in Switzerland, Holland, Belgium; this year I saw some very good young Finnish designers and others from northern countries or also Israel and Turkey. There are probably things moving that will inevitably produce others of quality, in cascades.

Misunderstandings about young designers

A Marco Romanelli. We should be careful on the subject of young designers. They are very often something that older people and institutions feed off. Each fair visited this year had its own SaloneSatellite, because it’s something that is convenient for the old, not the young. Really promoting young designers means moving in a much more concrete and realistic way, using money and offering real opportunities. If we truly believe in young designers, above all we need to invest. The impression is that very often in Italy the opposite happens: the young are asked to fill in our gaps, and compensate for our shortfall on a general cultural and organisational level.

A Beppe Finessi. Andrea Branzi is right; he always underlines the unfortunate peculiarity in Italy where the manufacturers, apart from some exceptions, have for years abandoned designers to carry out research in their own back room, their garage or in a larger studio when things start working. It is the designers who continue to experiment, taking the piece to be built to the company. As Marco Romanelli pointed out, the young designers at the Satellite continue to do this, to bring their hopes, their dreams, their research. Today companies first ask for experimentaion, then to present a prototype... In the meantime 80% of the young designers change career.

Design and contemporary art: the violence of the object

A Paola Nicolin. I would just like to add a brief comment on this question of young designers or at least on education in Italy. For what little direct experience I have of the world of contemporary art, I think that the famous “Italian design effect” is extremely evident in the work of Italian artists aged around 30-35 who do not explicitly declare themselves to be designers but are linked in varying degrees to this field. I am thinking of people like Patrick Tuttofuoco, from his early works right up to his latest exhibition “Revolving landscape”. His is the story of an artist who grew up in the surroundings and myth of Mari and Munari. He has always greatly admired the radical nature of their work without ceasing to translate the effect into something contemporary. He has chosen to represent his ideas of objects in a different language, that of art. The most extraordinary thing that I happened to see outside and inside this fair was its echo in contemporary art. I have noticed the spread of a homologated exhibition criteria where the fair is like a sequence of objects. It has passed to the Furniture Fair from Miart with no break, like a single event that hits the city and then disappears without trace. This “violence” of the object, which arrives before the concept, is also seen very much in that slice of contemporary culture to which design is often attached. Many of the art exhibitions opened during the Furniture Fair brought together very fine works of art but the way of representing and displaying them was similar to Fair-like criteria, which dilute the concept. It is no longer a question of concept, but of how it is represented. Mine is not an aesthetic judgement, it is just a fact of logic, a possible reasoning on how this exhibition situation spreads like oil and becomes a principle of homologation that touches every sphere of representation.

The schools

A Italo Lupi. On the subject of schools, it seems to me quite useful to underline that one of the most interesting things at the Furniture Fair was the exhibition “Post Mortem” by the Eindhoven Design Academy. Whether it was good or bad, it put forward an argument that is absolutely taboo and up until now one that has not been addressed. Even the choice of location, the Faculty of Theology at Italia Settentrionale, showed great intelligence. It was a very Dutch exhibition, but also very Victorian in the way it took a number of elements – the tear collector, the small necklace with a lock of hair inside, the pall that covers the coffin – which in that era were serial produced. The very Dutch approach was to put forward a theme that is not normally addressed. Why don’t Italian schools offer the same kind of intelligence, at least as debates or discussions?

d Joseph Grima. Holland was the first country to address the question of conceptual design, in other words start with a concept then transform it into an object, even a banal one, with a series of meanings. Returning to the question of the schools, I would like to if I may offer a view “from abroad”. I think there has been a very privileged season in Italy for some designers – who, however, are almost all foreigners. I think there has been a very privileged season in Italy for some designers – who, however, are almost all foreigners. Jasper Morrison, for example, had the opportunity to work with Magistretti and become acquainted with a model in which the designer worked closely with the producer. Morrison, like others, then transposed these experiences onto a completely dislocated model, a long way from the places where manufacturing takes place. In Italy, the direct relationship with the craftsman, lessened with de-industrialisation, has not been substituted with a scholastic apparatus able to fill the void. But on the other hand, considering Italian design overall, the situation is perhaps now more vital than ever. I don’t think there are many other epicentres in the world of design criticism that are as strong as our two magazines. The biggest furniture fair in the world is here, and the companies, even if they don’t use Italian designers any more and no longer produce in Italy, are mostly Italian. It’s a strange paradox.

A Italo Lupi. Perhaps in Italy there has never been a tradition of real schools but of the workshop. People like Magistretti or Castiglioni talked not just with the owners of the companies but also with the workers, excellent prompters of technical and aesthetic solutions. There is a lack of direct contact with a workforce that had, and I think could still have, extraordinary intelligence.

University

A Fulvio Irace. I asked myself what place the university could have in educating the young. It is unfortunately a role, I don’t want to say totally absent but certainly very much in crisis, that doesn’t really offer either an authentic education or experimentation. Design or art faculties often offer very legislative, jumbled responses, also in the definition of the study programmes. Incapacity to give clear definitions is therefore manifested along with an obsessive desire to multiply degree courses. If these faculties were organised in an intelligent and diversified way, they could take account of their different cultural contexts. Instead the model tends to be homogeneous and widespread, often competing on a national scale, from the moment in which there exists a market of students. A surreal situation is created, that is born out of the application of concepts and parameters born in contexts strongly influenced by production to situations in which production is a mythical mirage, distant, vague. The problem, which also regards faculties of architecture and their crises, is that we have moved from a substantially humanistic model, founded on strong craftsmanship and authorship of the person of reference, to a kind of European Esperanto that has perhaps destroyed the culturally anarchic good that we had produced. There is a need to understand whether we should assume a position of defending values that belong to a system that is very dear to us but that undoubtedly, if observed through disenchanted eyes cannot but appear to be in extinction, archeological; or if instead we should take steps, I don’t really know in what direction, to invent a new model that is able to offer answers. Ride through this crisis therefore with a planned approach.

Aesthetics and Politics

d Marco Belpoliti. I teach Italian literature but I don’t think my students will all become writers. In the same way, those who teach architecture or design shouldn’t think that their students will become famous designers. There is a problem. The job of designer is highly aristocratic, whereas we live in a democratic system and democracy asks for average or above average quality products to go in everyone’s home. This is the paradox of democracy. The journey we should make is to finally return from the aesthetic to the political, after we left politics and we arrived at art. Let’s not forget that people like Mari or Munari came from a political past where art was substantially the extension of politics using other means. I think that, as has happened in publishing, there are parameters substantially dictated by marketing from which one cannot escape. But marketing – here’s the paradox – is a result of democracy; it is not only the effect of turbocapitalism that wants to earn more. It is democratic request: one wants to achieve standards that everyone can share. While the job we speak of and the types of products that come out of it are exactly the opposite, they are absolutely aristocratic. I think of the graphics that everyone does on the computer now. From a certain point of view they are perfectly right, on the other there is a need to counter this trend. I think that design schools should be closed, not opened; there should be less of them or they should be harder. Opening the future in a democratic way will be, as it already is, for managers and advertisers. I think the only answer is to move from aesthetics to politics. But it is a totally aristocratic road to make incomprehensible and indigestible things that bear no relation to aesthetic or traditional canons. Like the title of the film by Atom Egoyan, Where the truth lies, we live in a world of false truths. The only way out is to take the political element to heart. Of course the problems that we have thrown out of the door come back through the window, we can’t ignore them, they are political problems, of democracy. Is democracy the best of possible worlds? I’m starting to think not.

Craftwork

A Marco Romanelli. Aesthetics has always been political. During this Furniture Fair a very strong democratic force re-emerged: that of craftwork. The world of the marketing manager has found itself to be strangely juxtaposed with that of the artisan. We have begun to see the revival of certain aspects, an attempt to soften certain lines, to tell certain stories. Some examples? A work such as that of Bernardaud, with a very valid concept, taken up by Enzo Mari, by the worker who became a designer by intervening on the production cycle; or the retrieval of the Biscuit done by Royal Tichelaar Makkum with the studio Job, this was also an extremely precise issue of craftsmanship; or the initiative promoted by Renato Soru, in which I was personally involved, regarding the relaunch of Sardinian craft. It isn’t true that only big manufacturers can afford refined craftsmanship. It is almost the opposite. Producing with very cheap technology in China or India where work costs less creates a huge problem in quality control. Addressing this reality therefore often means returning to look at primitive structures of production, in other words forgetting the extraordinary ability of the craftsmen of Roberto Poggi and Cesare Cassina. They are small companies where things are still made by hand. The problem of democracy, mass, marketing, produced for everyone is therefore very complex. Decoration, which brings with it a revival of craftsmanship, could for once be quite an interesting way out, and it is certainly a new thing institutionalised in this Furniture Fair.

Design pollution

d Marco Belpoliti. It is true, aesthetics is politics, without a doubt. Now like never before design is politics, for this reason there are managers, because politics is once again joined to democracy. I think we also need to start talking about design pollution, and not return to the past. Why must everything be designed? Why does everything have to look nice? If you want to say something different, maybe you need to stop giving marks like teachers and also admit this form of exaggeration. Design thrives off itself, and it is normal that it is like that, but now perhaps in a way that is pathological. A visit to the clinic wouldn’t be a bad idea.

A Fulvio Irace. It was written in the destiny of modernity. At the end of the day the avant-garde has fulfilled itself in an unexpected way. It was destiny that the beautiful would have changed the world. I agree that we are experiencing the whiplash of a utopia that has suddenly been realised contrary to our expectations, and this beauty hasn’t made us better or happier. But if we return to the notion of aesthetics, which is not the science of beauty but the art of sensations linked to forms, we are effectively living in an aesthetic moment, where the issue of good taste, the beautiful and the ugly, is out of date. This question was posed with great force in the 1970s and ‘80s, by the Radicals, by Mendini. Years, also in Domus, that cost blood and tears, when there was a dusting-off of Abraham Moles, Kitsch and thoughts that were totally out of order in the Italian cultural context. I think that we should free ourselves not so much of the obsession with aesthetics but of the obsession with beauty.

A Marco Romanelli. I have the impression that even among us one basically continues to think of design as a superstructure. There’s nothing that hasn’t been designed. One can decide to use a non-design in design, but things that a person has not designed don’t exist. We should stop thinking of design as the cherry on the cake; design is the cake. When I observed at the beginning that we should seek out everyday objects, this is what I meant. It is necessary to return to a formal control that also means the everydayness and usefulness of the object. Let’s not forget that phenomena like Muji exist, people who for better or worse have philosophically chosen this kind of route. Perhaps even we can simply seek to point less at design of “exceptionality” and return to consider the design of “quality” as the overall, and therefore also as aesthetics-politics.

A Beppe Finessi. Our two great angels, Munari and Castiglioni, collected objects to award the Compasso d’Oro to the anonymous, recognising in these not just a part of quality but also a part of design.

d Marco Belpoliti. They collected anonymous objects because in any case they carried out a named trade, and this was a necessity. Perhaps what has been lost, and what is being lost, is the return to a more dialectic aspect. In the objects that Domus chose luckily there was no necessity. I found them very random. They are a “shake”, a cocktail made by a true barman, without stars there with the measuring cups like we do when we cook. The thing that interested me most was the solar kitchen. It was beautiful because it responds to something ethical. For me ethics is ethos, custom. This country has lost its ethics because it has lost its customs. I am referring to what Pasolini talked about in Scritti corsari, the kind of landscape and how one dressed it. Today everything has a label: there is a deliberate will to design and sign things. At times this will doesn’t leave space to randomness, which we have a great need for.

Fuksas’s new Fiera

A Italo Lupi. We haven’t talked much about the new Fiera and the phenomena that it may have induced, desribed at times by the press in a dramatic way that in my personal experience does not coincide with reality, even though the transport connections should be reinforced. However visitors moved outside the city for the greater part of the day, for which reason Milan experienced the days of the Fair in a different way. From what I could see, the city came alive in the evening, whilst during the day there were less troupes of designers dressed in black wandering around. Trying to forget the eyesore that they will make of the old Fair area, it was very entertaining in the new Fair to lift up one’s eyes, tired of too much furniture, to the high windows of the pavilions and see this white whale that floated outside, very beautiful also seen in segments, with an uplifting sense of the new.

D Stefano Boeri. Fuksas has made the ritual of the Furniture Fair more theatrical and spectacular. His Fiera is a huge expressive machine, that celebrates the ritual of the crowd “at work” that flows in and out of the pavilion. Apart from that, a vist to the Fair has always been a tiring, long, extenuating journey, made by a multitude of solitary individuals brought together by the same gestures...

A Fulvio Irace. For the first time we have a Fiera that is a city of trade, organised according to the principles of a single project, a kind of microcity of exchanges and flows. On the other hand we have a centre, that until now has always been an alternative with respect to the chaos of the Fiera area, that is the city, that offers itself like a kind of labyrinth, an archipelago of islands, according to the meaning ascribed by Stefano Boeri. One could think, perhaps with an excess of optimism, that the occasion of the Furniture Fair week in Milan could be studied, also from a design and sociological point of view, as an attempt to simulate a city of creatives, regulated therefore by exceptional rules that are not the usual planning ones. There has been no better attempt than that of the Salone to evaluate and promote run down areas, to create charisma for the city, to make Milan for a week, a charismatic city, like other European cities are throughout the year. From this point of view, the success of the new trade fair centre helps to reinforce this charisma, offering for the first time to the public the image of creativity inside institutions: in other words, alongside the anarchic model of the private initiative, the Rho Fiera has born witness to the interest of the institution to present itself dressed in efficient and attractive modernity, not being pulled along, but doing the pulling.

Stitching Wood: Lissoni’s Latest Creation

Part of Listone Giordano’s Natural Genius collection, Nui is a series inspired by an ancient Japanese technique.