Three stories of Superstition and Protection

New York, October 2005. In the year of magical thinking, in keeping with the title of Joan Didion’s touching memoir which chronicles her husband’s death and how her daughter fell into a coma, safety is an elastic band suspended between the floor under the asphalt and the floor under the rooftops. Beneath the asphalt there is the usual news two-step: alleged attacks on the subway; the Post publishes a fake story that the financial and political elite “had been warned” not to use any of the lines so superbly illustrated by Massimo Vignelli. In the fine, driving rain, the paranoia is more subtle than the rain, which seeps in everywhere. The state of paranoia is a sequence of verses that rhyme with anything. Meanwhile, above the roofs, design returns to the MoMA after some major manoeuvring in recent years with an exhibition entitled “Safe”. Curated by Paola Antonelli, it is a remarkable collection of objects intended to protect, defend, save, isolate, hide and safeguard. The exhibit’s muddled design stimulates more ideas than it produces. After all, when you decide to deal with an idea in the shape of a device, the only path is that of stimulation: call friends, write to enlightening people and remember, in English people say “safe and sound” – perhaps because really dangerous things always multiply in silence.

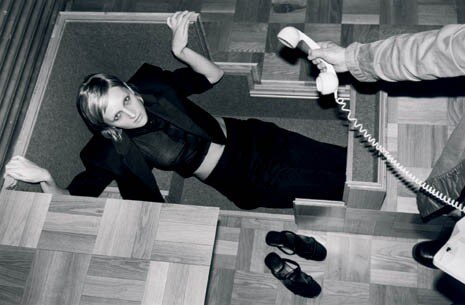

Manhole

I dined with Achille Varzi near Columbia University, where he is an associate professor; he is one of the liveliest and most interesting minds on the philosophical scene on either side of the Atlantic and a genuinely pleasant individual. I told him about some of the objects I had seen at the MoMA: boxes, internal spaces, soft shells that protect demonstrators against police batons, hard shells that avoid fractures in an accident. He and Roberto Casati wrote a book about holes that took him away from the depressing Italy of the hereditary university and brought him here to 116th street, one of the poles that made 20th-century New York a system of culture production that has seen an efficient renaissance. Inside a bag I have a copy of Jed Perl’s excellent book New Art City, a critical tale of the artistic Manhattan of the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s. It’s like a Robert Altman film scripted by Roberto Longhi obsessed with Rothko. “I have spoken to more knowledgeable people than me about it; it is perhaps a little elementary, but over the years I have developed a theory on how architecture, town planning and design evolved. It is a whole series of niches, spaces drawn from solid matter to protect people against the void outside, against the holes.” All cities are made up of an exchange between holes emptied of matter and full holes. After all, it is about a problem of perception. I tell him about the manholes and he shows me a catalogue of photographs of New York City manhole covers, each one with a different pattern and design, all of them magical. Then it is the turn of Laura Di Summa, a young philosophy of mind scholar. “Manhole covers are the holes of the city covered over. Take animals for instance, the degree of survival and so-called superiority often lie in their architectural defences which allow them to perpetuate, to accumulate. The honeybee described by Darwin survives and surpasses the stingless bee because of its ability to construct cells. The architecture of holes, that which opposes and reverses vertical organisation, is a principle of conservation and of motion.” I put down the book of photographs and picked up the exhibition catalogue again. I opened it at the right page and put it on the table. There is a prototypical, cunning, inevitable manhole. Varzi added: “Exactly, just look at what the word means: hole for a man.” Before we rise, I bring up a much-loved expression, constructed space. It’s a shrewd way of describing nearly everything that interests us: constructing space; digging holes; hollowing out the ground; protecting people against the air because the air seems infinitely empty – but that is just appearance.

Touch everything three times

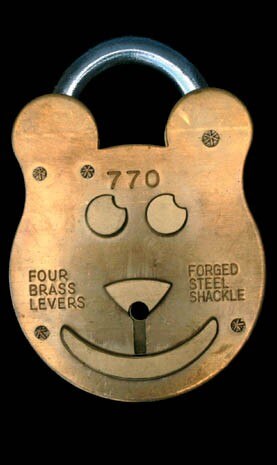

For some time I toyed with the idea of describing how superstitious individuals walk - note that the Italian word scaramantico (“superstitious”) contains the onomatopoeia “tic” - with their shoulders jumping unintentionally and fingers that give off shocks, but also actions intended to ward off evil. Manhole covers are ideal talismans. A fair percentage of the Western population spend their days trying to remain attached to solids, to corners, to walls, to testimonial proof that we are still alive – as if every move hid a forced entry, an exit from the circle of existence, an un-constructed hole. Most of the objects amassed for “Safe” are hugely attractive to the superstitious. As we know, design objects lie. They swell up, extend, spread out; they are disguised; they adopt unreliable identities. But none lie with the untroubled cruelty of a box of nails that conceals large quantities of gold – the reasoning behind the most powerful anti-theft device is the dissimulation of wealth. Nothing hides with greater excitement than the splendid iron mask that protects the human face against bullets – I wonder if anyone over in Israel, where it was designed, has ever tested it. In this exhibition entitled “Safe”, with all its holes and barriers venerating safety and an indifference to fear, it appears that I am surrounded by many objects on MoMA’s top floor that are simply not telling the truth. Because, belying the cliché, the best offence is the worst defence.

Hidden orphans and jewels

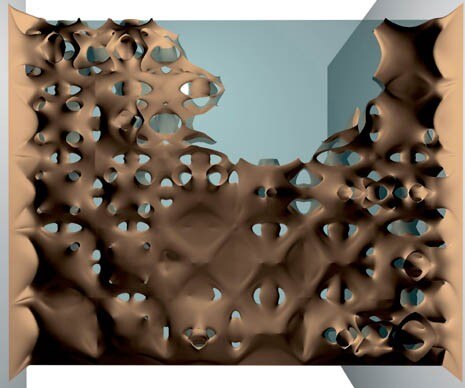

My most robust idea on the subject of safety came to me via a short story by J.G. Ballard entitled Running Wild. It is pure Ballard, a fairly tense little piece that’s bound to the north by prophesy and to the south by anthropology. Set in the year 1988, it’s about a luxury residential neighbourhood for London’s super-professionals outside the city, protected by medieval walls and closed-circuit TV. It has a progressive atmosphere with well-raised children who have everything, i.e. educated middle-class types. One morning all the parents are found murdered and there is no trace of the children. After a few weeks, they discover that the well-educated teenagers had killed their parents because they were in an over-protected environment. Of course, the story was not intended to be summed up in the words of an investigator, and there is not a single explanation why manhole covers are touched three times, why crazy murders are committed, or why valuables are hidden among junk. It is primarily used to maintain a balance, the ideal of undermined situations, properties and lives, the most human and understandable instinct you could imagine. However, nothing explains why the life of the cities, the houses, the families or the individuals makes more sense within this baroque safety, something which is desired by the large consultancies steering the priorities of corporations and governments. One of the most moving objects presented at “Safe” is called Cries and Whispers, a sort of soft woollen cave designed by Hill Jephson Robb for his sister, who died prematurely and left behind a baby girl. It is a niche for orphans that reproduces the lost placenta. Yet some fears cannot be exorcised by superstitious rituals or inventive protection. I could have done with Cries and Whispers eight years ago when I was twenty, and not just a few months old. But in a certain sense I did not need it. In a wireless café, while receiving news via email that the bioethics philosopher Peter Singer had nothing original to say on the question of “Is it ethical to aspire to safety as an absolute value?”, I was reminded of an afternoon when I was a child. We were getting off the bus and my mother started to tell me the story of an elderly woman, whose name I recall was Helga. A Jewish woman, she knew she was being hunted by the SS and decided, I can’t remember how, to slip a number of gold leaves detached from necklaces and other fine family bracelets under her skin. When someone spoke disbelievingly to her about this she would look at them for a few moments and touch the base of her neck. Visible beneath her skin was a sort of coin that the Jewish woman called her sounding. The jewels and gold leaves shone beneath her fine skin like tissue paper covered with a thousand wrinkles, a bit like rhombuses on a huge pre-Columbian leaf. I do not know how the story ended, not because I’ve forgotten, but for the simple fact that all my mother’s stories ended halfway through. The same happens, conceptually speaking, to all the speculation and productions regarding safety. They are objects and events constructed for the moment when. But the moment when never arrives, or only arrives on a few occasions; it may arrive late or when there is no way to protect yourself, at a moment when you are dreaming about being safe.

Seamless design, ECLISSE steps outdoors

ECLISSE introduces Syntesis Areo Outdoor, extending the sleekness of its flush-to-wall system to exterior applications. Robust and adaptable, it reimagines technical access points as integrated design features, ensuring a continuous aesthetic flow between interior and exterior spaces.