Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani (Rome, 1951) is an overall atypical character in the architectural field of our time. For decades he has been actively participating in the debate on the contemporary city, as well as in its construction. At the same time he has been virtually unaffected by that self-promotional trend that involved many of his peers. Magnago Lampugnani is anything but a star architect, as intended since the years 2000; he rather draws inspiration form the figure of the architect-intellectual, as defined for instance by Marco Biraghi in 2019.

Magnago Lampugnani is a deeply European architect, in many regards. First of all, the geographies of his biography are European. He studies at La Sapienza University in Rome and then in Stuttgart, where he obtains his master in Architecture and later his PhD, in 1977. He gets a second doctoral title in Rome, also at La Sapienza University, in 1983. He founds his firm office in 1980 in Berlin, and right after in Milan (Studio di Architettura). To conclude, in 2010 he constitutes with Jens Bohm the Baukontor, a design atelier based in Zurich. Italy, Germany and Switzerland remain the three fundamental poles of his whole career.

Starting from the early 1980s and for at least a decade, Magnago Lampugnani is pivotal in the theoretical reflection and the material transformation of a major European capital, Berlin. Between 1980 and 1984 he is scientific consultant for the IBA – Internationale Bauausttlellung, a decade-long program for the realization of new dwellings for 30 thousand inhabitants of West Berlin, to be achieved by 1987. Within the IBA, Magnago Lampugnani shares the position of its director Josef Paul Kleihues on the need for a “critical reconstruction” of the historical city, which replicates its urban plan and its architectural volumes.

As opposed to the hiatus introduced by the postwar Modernist city, and in direct contradiction to the whimsical shapes of deconstructivist Berlin – better shown by Peter Eisenman building at Checkpoint Charlie (1985-1986) – Magnago Lampugnani positions himself as the theoretician and the constructor of a “Berlin of stone”, rooted in its Baroque and 19th century tradition. The office complex “Block 109”, realized with his wife Marlene Dörrie and completed in 1996, is the most massive three dimensional translation of a wider, cultural reconstruction of the representations and imageries referred to the German city.

View gallery

View gallery

Baukontor Architekten, Office building in Schiffbauplatz, Zurich, 2015. Photo © Seraina Wirz. From Domus 1018, November 2017

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Novartis Campus, Basel, 2008. View of the interiors. From Domus 934, March 2010

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Novartis Campus, Basel, 2008. View of the interiors. From Domus 934, March 2010

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Novartis Campus, Basel, 2008. View of the interiors. From Domus 934, March 2010

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Jens Bohm, Francesco Porsia, Richti Neighborhood, Zurich, 2013. Photo © Karin Gauch-Fabien Schwartz, Maximilian Meisse. From Domus 986, December 2014

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Jens Bohm, Francesco Porsia, Richti Neighborhood, Zurich, 2013. Photo © Karin Gauch-Fabien Schwartz, Maximilian Meisse. From Domus 986, December 2014

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Jens Bohm, Francesco Porsia, Richti Neighborhood, Zurich, 2013. Photo © Karin Gauch-Fabien Schwartz, Maximilian Meisse. From Domus 986, December 2014

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Jens Bohm, Francesco Porsia, Richti Neighborhood, Zurich, 2013. Photo © Karin Gauch-Fabien Schwartz, Maximilian Meisse. From Domus 986, December 2014

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Open-space work stations, “Akoe” collection for Unifor. From Domus 1000, March 2016

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Parking garage, East Hanover, New Jersey, 2013. Photo © Paúl Rivera. From Domus 1010, February 2017

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Parking garage, East Hanover, New Jersey, 2013. Photo © Paúl Rivera. From Domus 1010, February 2017

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Parking garage, East Hanover, New Jersey, 2013. Photo © Paúl Rivera. From Domus 1010, February 2017

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Parking garage, East Hanover, New Jersey, 2013. Photo © Paúl Rivera. From Domus 1010, February 2017

Baukontor Architekten, Office building in Schiffbauplatz, Zurich, 2015. Photo © Seraina Wirz. From Domus 1018, November 2017

Baukontor Architekten, Office building in Schiffbauplatz, Zurich, 2015. Photo © Seraina Wirz. From Domus 1018, November 2017

Baukontor Architekten, Office building in Schiffbauplatz, Zurich, 2015. Photo © Seraina Wirz. From Domus 1018, November 2017

Baukontor Architekten, Office building in Schiffbauplatz, Zurich, 2015. Photo © Seraina Wirz. From Domus 1018, November 2017

Baukontor Architekten, Office building in Schiffbauplatz, Zurich, 2015. Photo © Seraina Wirz. From Domus 1018, November 2017

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Novartis Campus, Basel, 2008. View of the interiors. From Domus 934, March 2010

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Novartis Campus, Basel, 2008. View of the interiors. From Domus 934, March 2010

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Novartis Campus, Basel, 2008. View of the interiors. From Domus 934, March 2010

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Jens Bohm, Francesco Porsia, Richti Neighborhood, Zurich, 2013. Photo © Karin Gauch-Fabien Schwartz, Maximilian Meisse. From Domus 986, December 2014

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Jens Bohm, Francesco Porsia, Richti Neighborhood, Zurich, 2013. Photo © Karin Gauch-Fabien Schwartz, Maximilian Meisse. From Domus 986, December 2014

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Jens Bohm, Francesco Porsia, Richti Neighborhood, Zurich, 2013. Photo © Karin Gauch-Fabien Schwartz, Maximilian Meisse. From Domus 986, December 2014

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Jens Bohm, Francesco Porsia, Richti Neighborhood, Zurich, 2013. Photo © Karin Gauch-Fabien Schwartz, Maximilian Meisse. From Domus 986, December 2014

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Open-space work stations, “Akoe” collection for Unifor. From Domus 1000, March 2016

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Parking garage, East Hanover, New Jersey, 2013. Photo © Paúl Rivera. From Domus 1010, February 2017

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Parking garage, East Hanover, New Jersey, 2013. Photo © Paúl Rivera. From Domus 1010, February 2017

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Parking garage, East Hanover, New Jersey, 2013. Photo © Paúl Rivera. From Domus 1010, February 2017

Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Parking garage, East Hanover, New Jersey, 2013. Photo © Paúl Rivera. From Domus 1010, February 2017

Baukontor Architekten, Office building in Schiffbauplatz, Zurich, 2015. Photo © Seraina Wirz. From Domus 1018, November 2017

Baukontor Architekten, Office building in Schiffbauplatz, Zurich, 2015. Photo © Seraina Wirz. From Domus 1018, November 2017

Baukontor Architekten, Office building in Schiffbauplatz, Zurich, 2015. Photo © Seraina Wirz. From Domus 1018, November 2017

Baukontor Architekten, Office building in Schiffbauplatz, Zurich, 2015. Photo © Seraina Wirz. From Domus 1018, November 2017

Most buildings completed by Magnago Lampugnani in the following years testify of a path based on remarkably consistent conceptual premises, and resulting in fairly uniform formal outcomes. Depsite the diversity of the specific commissions, over the years his architecture remains rigorous, orthogonal, non-decorative. This is witnessed by such projects as the Housing group in Maria Lankowitz, in the outskirts of Graz (1995-1999, with Marlene Dörrie and Michael Regner), the Entrance square of the Audi forum in Ingolstadt (1999-2001) and the Novartis campus in Basel (since 2001), as well as the more recent Parking garage in East Hanover, New Jersey (2013), the Richti quarter (2013, with Jens Bohm and Francesco Porsia), and the Office building in Schiffbauplatz (2015), both in Zurich.

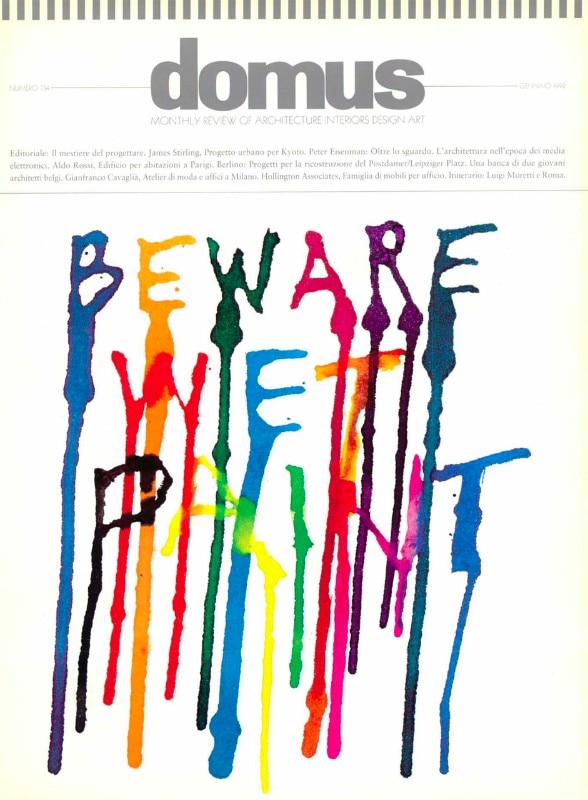

A less prolific practitioner than many colleagues, Magnago Lampugnani carries on in parallel a constant activity on research, criticism and dissemination of the architectural knowledge. Along his path he crosses several of the most prominent European institutions in the field: magazines such as Casabella, where he is member of the editorial board between 1981 and 1985, and Domus, that he directs between 1992 and 1996; museums as the DAM – Deutsches Arkitekturmuseum in Frankfurt, that he guides between 1990 and 1995; universities such as the ETH in Zurich. He joins it in 1994 and he remains Full professor of History of urban design until 2016.

These are the most relevant episodes of his steady engagement on several fronts in the European architectural debate. This includes also the regular publication of monographs and essays – Bedeutsame Belanglosigkeiten. Kleine Dinge im Stadtraum (Small objects in the urban space, Wagenbach, Berlin, 2019) is one of the latest – the participations in committees and juries, for instance for the EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture – Mies van der Rohe, and the collaboration with Swiss daily newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung.

In the words of the editorial board of Domus:

With perfect aplomb, thanks partly to an Italian-German training that prompted him to state, with some irony, 'there is no urgency that cannot wait', he managed to calmly mediate the enthusiasms and attritions of editorial life, relying on his aptitude for synthesis and fast decision-making. His many relationships with figures from the international world of culture, which enriched the magazine’s panorama, were also cultivated with a reserved and affable yet firm approach, boosted by his easy command of four languages