‘Adorned with much wisdom and very astute in military matters as any other captain of these days.’ This is how Cherubino Ghirardacci, an Augustinian friar and historian of the sixteenth century, describes one of the most enlightened men of the Renaissance: Federico da Montefeltro.

Federico da Montefeltro became Duke of Urbino in 1444. He acquired wealth and built a court whose fame spread throughout Europe. Among the most refined patrons, he invited intellectuals and many artists to his court, including Paolo Uccello, Leon Battista Alberti, Piero della Francesca, Donato Bramante and the architect Francesco di Giorgio Martini.

The deeds and the duchy of Federico da Montefeltro have found their space in multiple tales, several books and works.

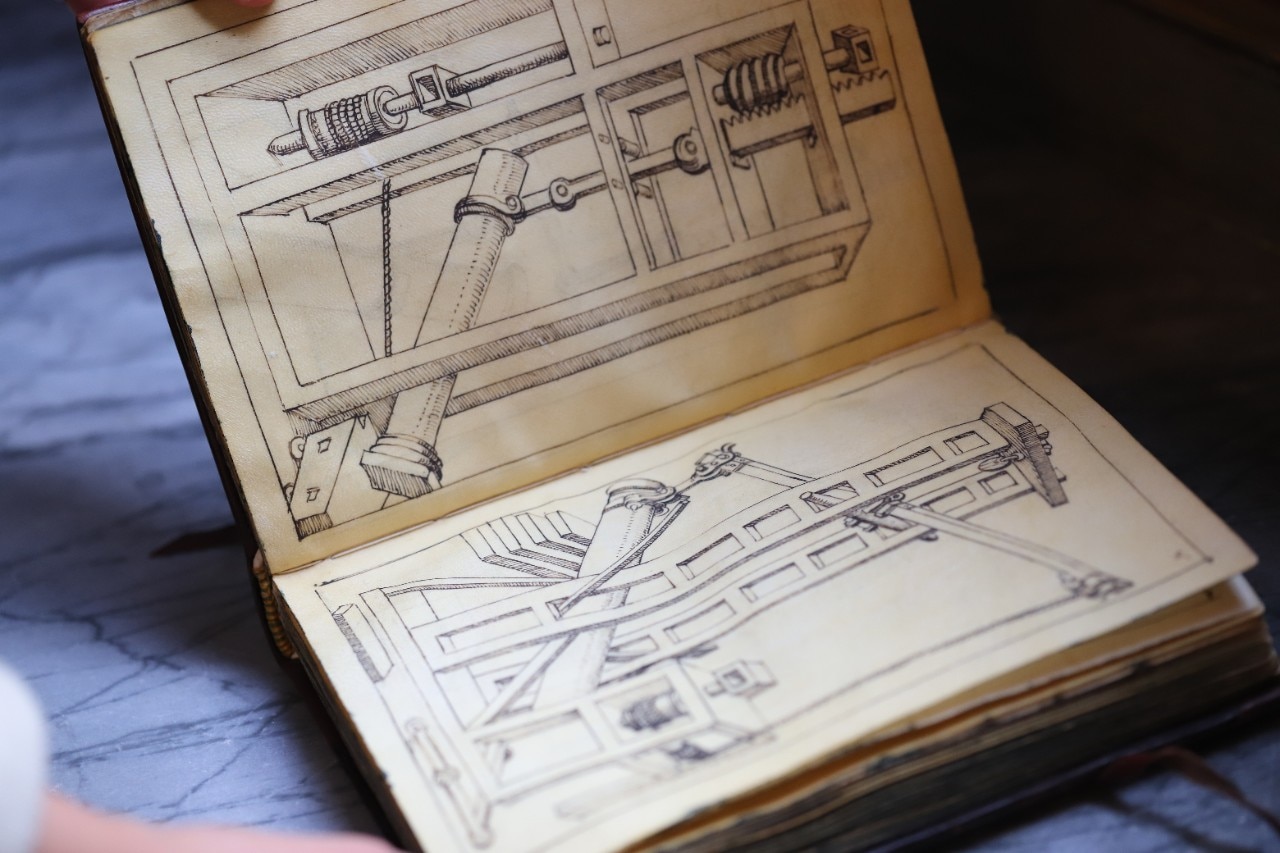

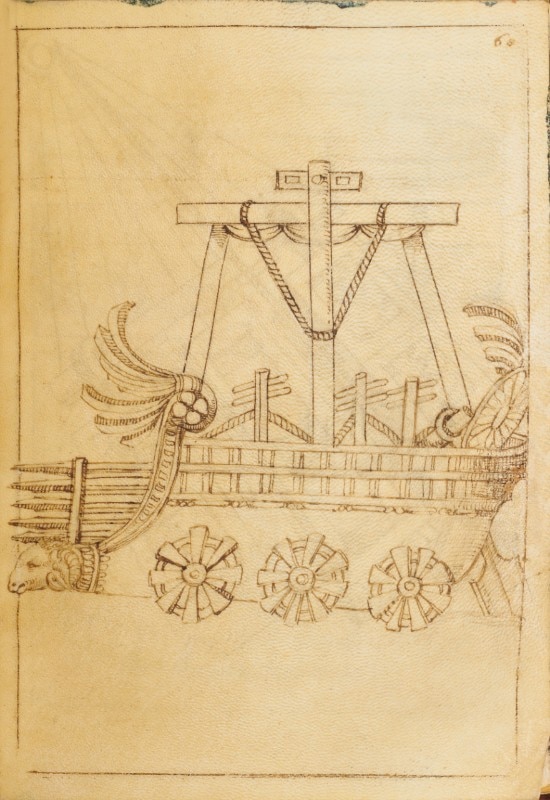

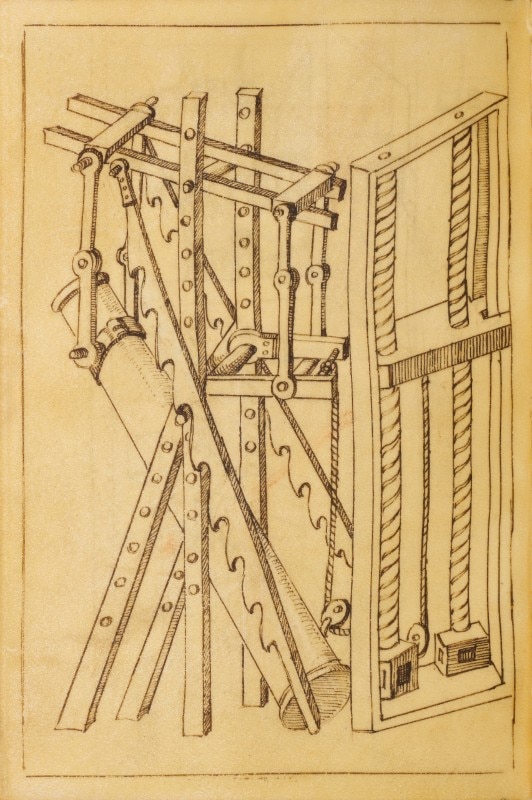

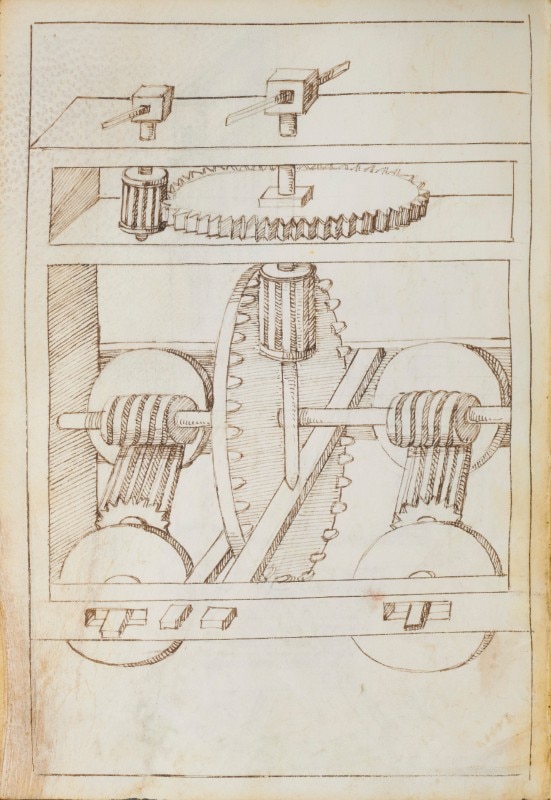

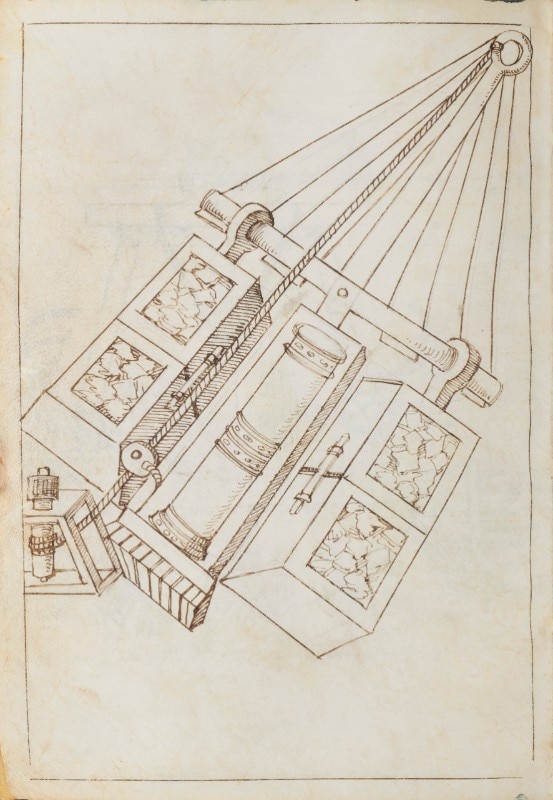

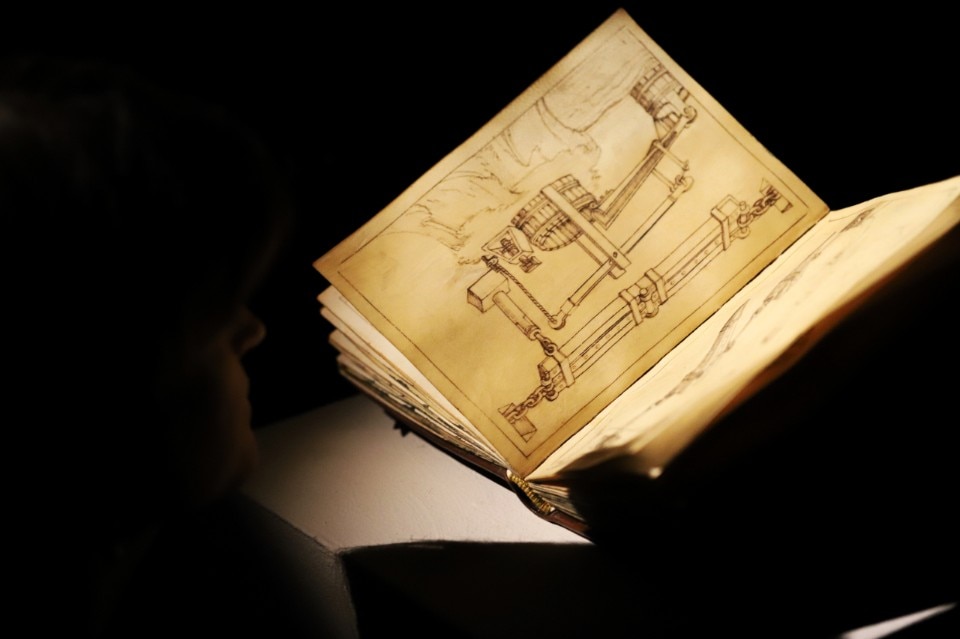

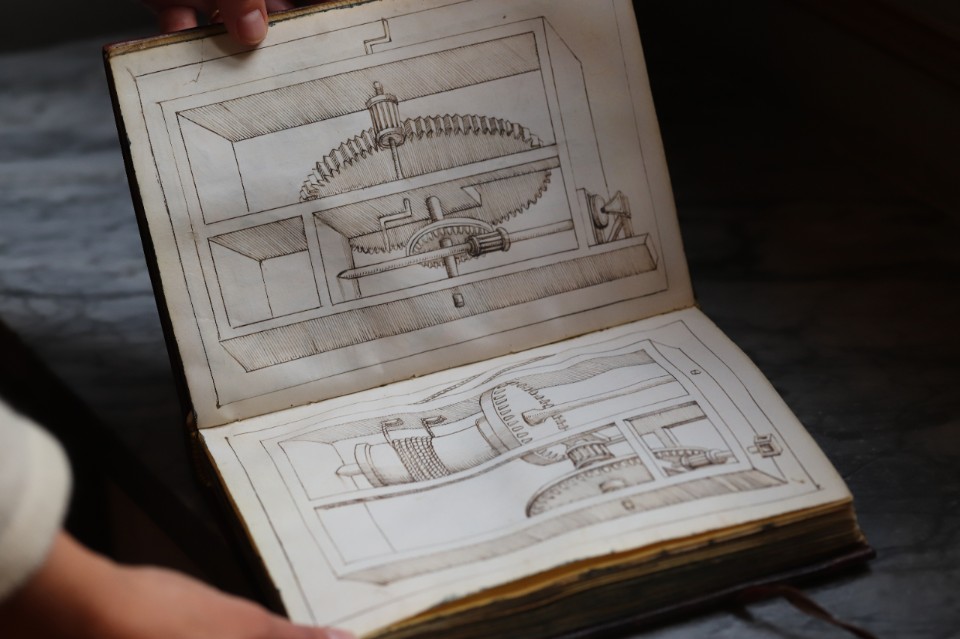

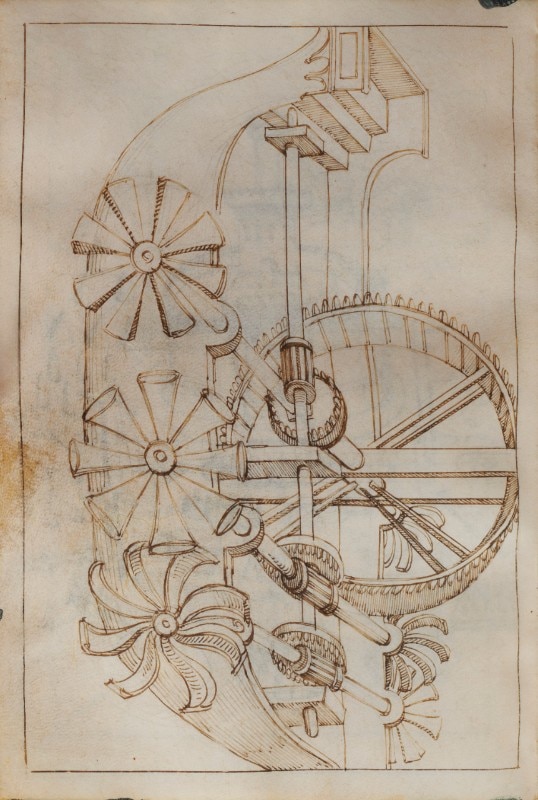

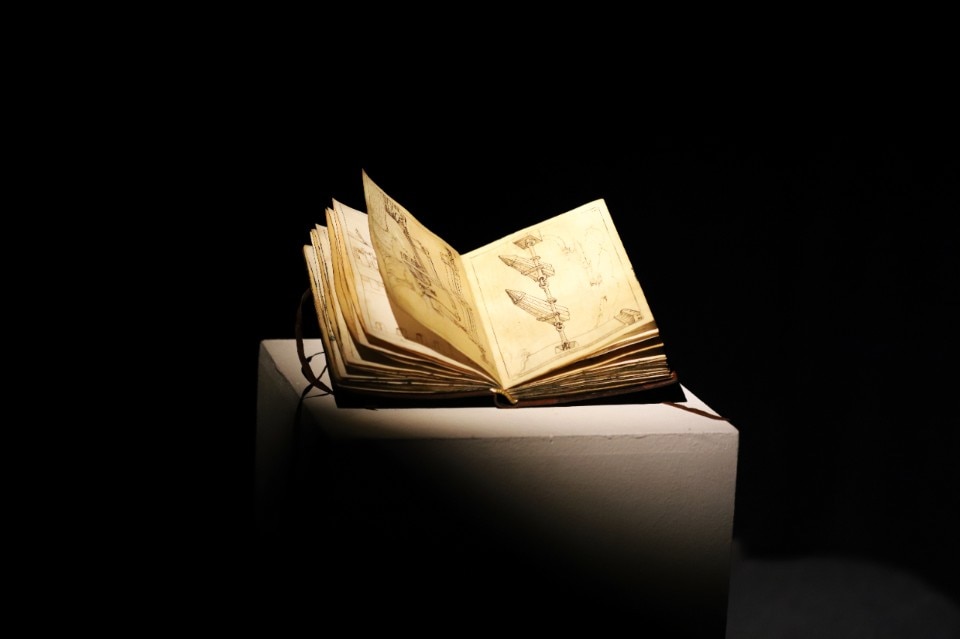

Many legacies were left to his beloved city, Urbino, which, for the sake of beauty, have found a new home in the halls of museums worldwide. These include the Montefeltro Altarpiece – also known as the Brera Altarpiece – and others more intimate, reserved, and equally precious, such as the Santini Codex – a parchment manuscript drafted during the Renaissance, right at the court of the Montefeltro and Della Rovere families, with the aim of glorifying the duchy’s hegemony in civil and military machinery.

The entry of the Santini Codex into the collection of the Dukes of Urbino is dated after 1498, as it does not appear in the Old Index, the first inventory of the Montefeltro and Della Rovere library. However, it does appear in the last inventory compiled by Francesco Scudacchi in 1632.

The Codex is thus the only one among the Urbino manuscripts to have remained in the city without being transferred to the Vatican Apostolic Library in 1657.

The manuscript finds an evident correlation in the work of Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1439-1501). He was both the author of the famous Opusculum de Architectura and likely the designer of the preparatory sketches for the seventy-two composition panels of the Frieze of the Art of War now housed at the National Gallery of the Marche.

Both the Opusculum and the panels of the Frieze serve the sole purpose of glorifying the virtues of the warrior-prince, Duke Federico da Montefeltro.

A recognized master for his remarkable skill in representing machines, Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1439-1501) was a student of Mariano di Jacopo (1381- c. 1453), better known as Il Taccola or the Archimedes of Siena. He learned from his master the art of engineering; a field then reserved for a small elite of intellectuals. This led him to establish a close relationship with Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), as evidenced by the latter’s annotations in the Ashburnham Codex 361. The meeting between the two took place around 1490 and was fundamental for the realization of the Vitruvian Man and for many of Leonardo’s works related to civil and military machines in the years ahead.

Pages of extreme beauty that could have thus inspired Leonardo, especially since during those years he was in Urbino. Extremely refined drawings that show the genius, skill, and talent of an author still uncertain for scholars, although he undoubtedly falls within the circle of artists close to Francesco di Giorgio Martini.

The scholar Gustina Scaglia considers the manuscript preparatory for the composition of the famous panels of the Frieze of the Art of War, while Professor Pietro C. Marani, President of the Ente Raccolta Vinciana in Milan, places it in the first decade of the sixteenth century but does not express an opinion on a potential attribution.

According to the scholar Grazia Bernini Pezzini: ‘The oldest known sources so far that depict images presumably derived from the frieze consist of two codices of drawings, one from the Vatican Library (Urb. Lat. 1397) and the other owned by the lawyer Santini of Urbino, both of them dating back to the sixteenth century [...].’

The Santini Codex will once again reveal itself in all its beauty at the Ponte Auction House on February 27th, with the hope that it may enter, like its more famous ‘colleagues,’ into some museum or library, with the aspiration that a new patron, a new Federico da Montefeltro, may acquire it and then gift this splendid volume to the many lovers of art, engineering, culture, and the Italian Renaissance.

‘The Renaissance and Leonardo died together,’ wrote the historian, military figure, and literary critic Gaetano Negri, yet the Renaissance continues to manifest itself through several works and pages of precious manuscripts.