Angelos Tzortzinis is a Greek freelance photographer who has been working on revolutions, repressions and refugees for almost ten years, with stories and publications that have earned him numerous awards, including Best Wire Photographer for Time Magazine in 2015, POYi, Sony award and Visa Pour l'Image.

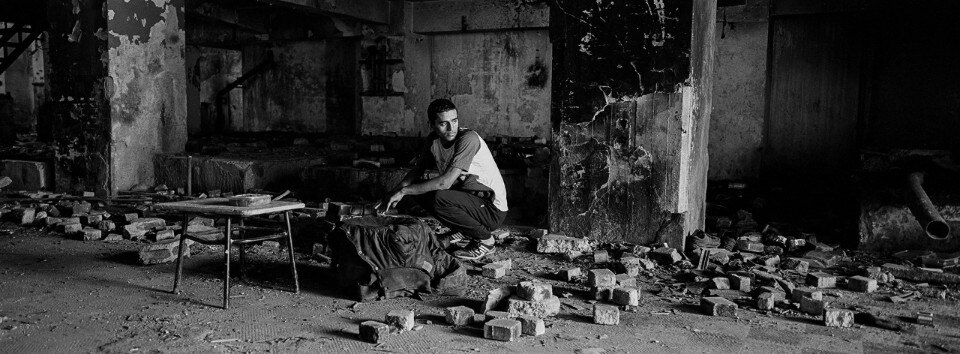

While honing his style and building his ethical approach with reportages on the economic crisis in Greece and the Arab Spring in Egypt and Libya, Tzortzinis began to focus all his interest on long–term projects revolving around migration and hospitality, with a particular attention to the representation of refugees, their wishes and expectations: in a nutshell, on the most exquisitely human aspect of the stories he stubbornly came across.

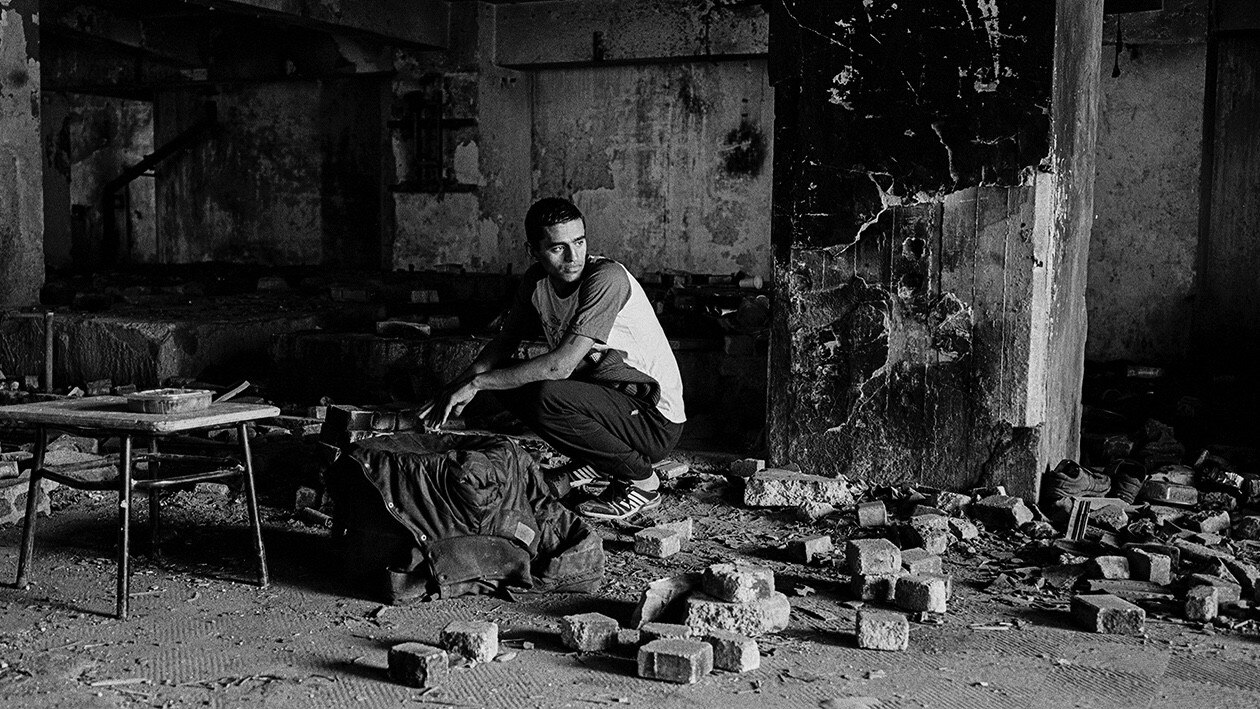

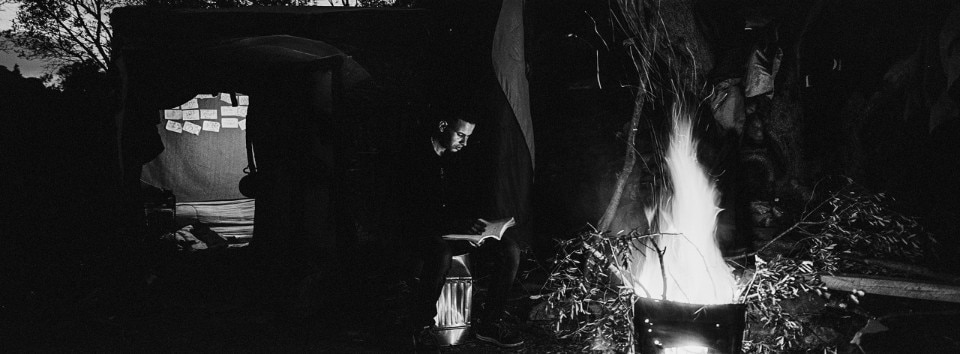

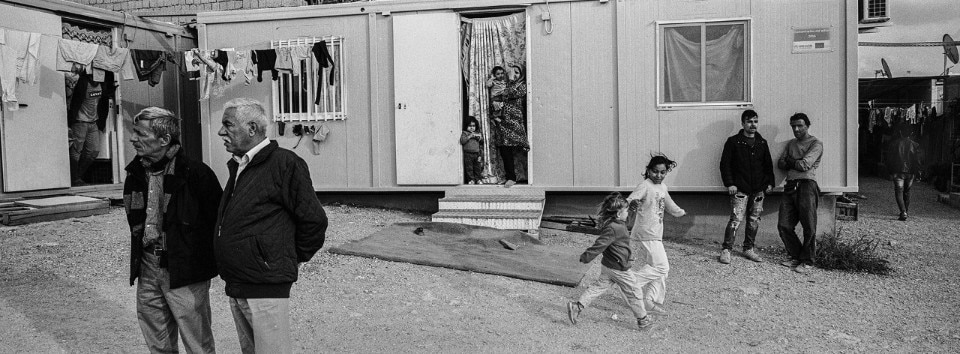

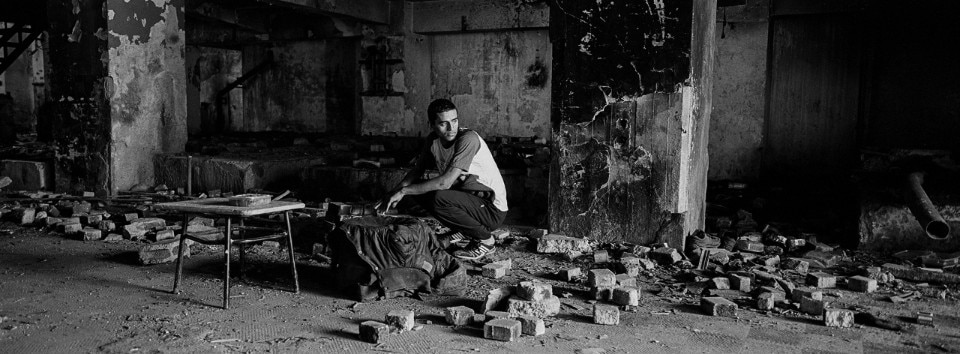

This year his Trapped in Greece, shot mainly on the islands of Lesbos and Somos, won him a World Press Photo as a story in the Long–Term Projects category.

For Trapped in Greece you used a panoramic format reminiscent of Koudelka, but your shots have a dynamism that almost gives the impression of being in front of a film. And, perhaps because of the subject matter or the fact that you are Greek, Angelopoulos comes to mind...

Koudelka’s important work has inspired a lot of photographers. As for me the inspiration came from film directors, you observed it very correctly. Theo Angelopoulos is a very important Greek director who influenced me, but those who inspired me to create this project were the Polish director Paweł Aleksander Pawlikowski, and the cinematographer Lukasz Zal. Ida and Cold War movies taught me how a simple story can become a masterpiece. Also due to dyslexia, a learning disorder I have, I always need to work within the limits that I set. So, the panoramic frame gave me the opportunity to work in these specific limits and helped me to be focused on the project. Someone who has been diagnosed with dyslexia could understand what I mean.

You have been working on the theme of migration for many years: which episodes have touched you most deeply?

A very difficult moment for me was when Balkans countries, the preferred route to northern Europe, sealed their borders, trapping more than 90.000 people in Greece. At this period I was in Idomeni, a village near the Greek north Macedonian borders, at a makeshift camp, where refugees and migrants were living in tragic conditions. These people lost their hope and they were devastated, because they could not continue their journey to another European country.

Also, a tragic moment was when a boat with refugees and migrants sank while attempting to reach the Greek island of Lesbos from Turkey, on October 28, 2015. I saw doctors and paramedics trying to revive children, I saw parents trying to realize the loss of their children. I couldn’t do anything to help, I felt powerless.

You have told the story of the refugee drama from different perspectives. How is the current humanitarian emergency in Afghanistan different from the others?

I cannot separate the refugee crises, they are all about humans. The only thing that changes is the connection that I have with my country. For this reason, the biggest part of my work so far has been about Greece, the place where I grew up and live. The lives of the people that I have captured during all these years are evolving along with my life, they become more mature and shaped throughout the years. Growing up in a neighborhood in Athens where refugees from Iraq had settled, who usually lived by five or six all together in one small room under insanitary conditions, and by being friendly to them, has led to my being familiar with their way of living from a very young age. I would also like to point out that I used to and still live in the heart of the problem every day, I wasn’t only a casual visitor.

If there is one thing that Biden and Trump have in common, it is that they have decreed, in discontinuity with Bush and Obama, the end of the hypocrisy according to which the mission of the United States was to export democracy throughout the world. How predictable was what is happening? And what do you expect to happen now?

As a photographer my job is to capture social issues in depth, not to take a stand on political decisions.

Cases like Danish Siddiqui's, but also Tim Hetherington's, Andy Rocchelli's and others before him, remind us that while in some ways documentary photography is becoming more and more conceptual—its boundaries blurred by technological innovations and cultural evolutions—many photographers continue to pursue a profession that cannot do without a direct relationship between the production of images and the reality depicted, even at the cost of losing their lives. But they are often only talked about when they leave. What drives photojournalists today?

The great photographers you mention above, including Chris Hondros, were devoted to their work for many years, their job was their life and they knew the risk, this is the difference about me today. If you want to be a war photographer you have to dedicate your life to your job. The photographers want to be on the front line in order to be able to discover the truth on their own. For me, this is what drives photojournalists to cover wars and conflicts.

One last question: what can photography do for refugees?

It wouldn't be honest to tell you that photography can change something regarding these people’s future. For sure there must be optimism in our lives, but people keep dying in their effort to achieve a better life. I am still not able to see a perspective of a better future, but I certainly hope so. So, for this reason I continue to work on this project. For me it is very important for people to learn what is happening on this serious social issue and through photography our goal should be to depict the story from our own point of view by trying to reveal what is hidden behind it.