This article was originally published in Domus 1054, February 2021.

Los Angeles, California, is the home of many assumptions that may surprise visitors from other parts of the world. Yes, it is sunny most of the year but we do get some rain.

We do have more automobiles than many other major cities but people do walk and take buses and trains. Our movies and TV shows have brought LA to homes around the world, although many wouldn’t recognise it when it pretends to be somewhere else.

The persistent stereotype of LA is a city without art. But there is great art in LA if you know where to look.

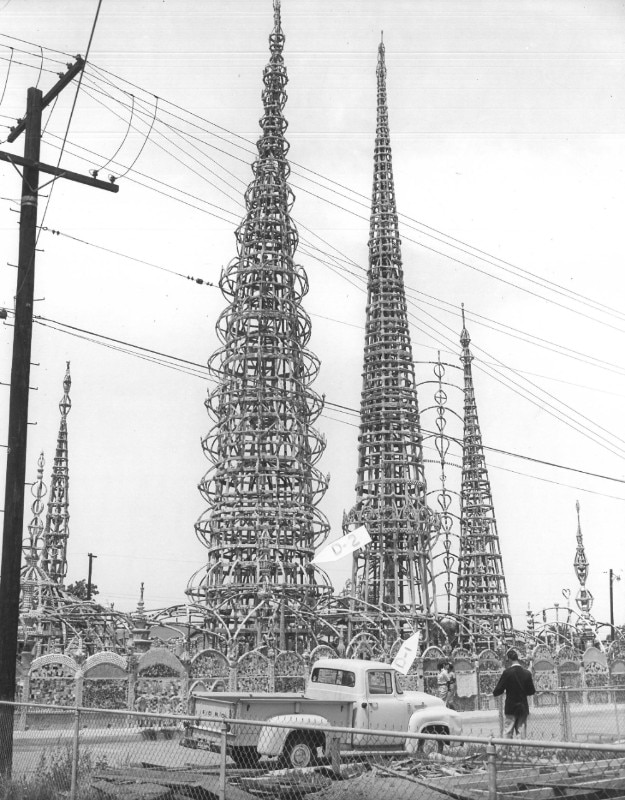

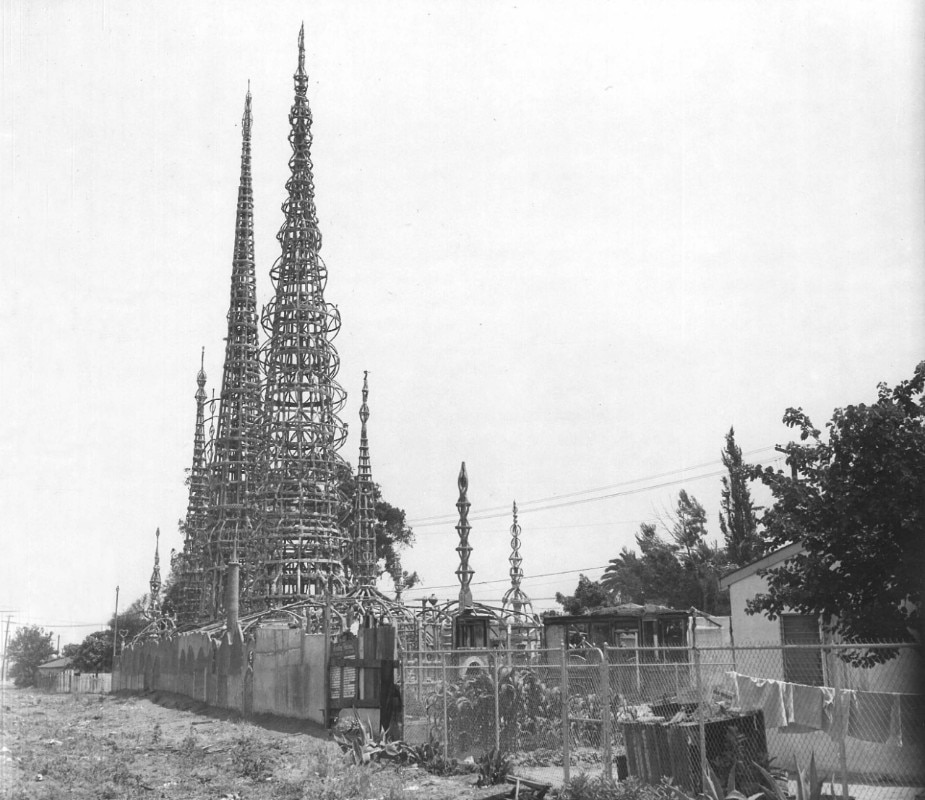

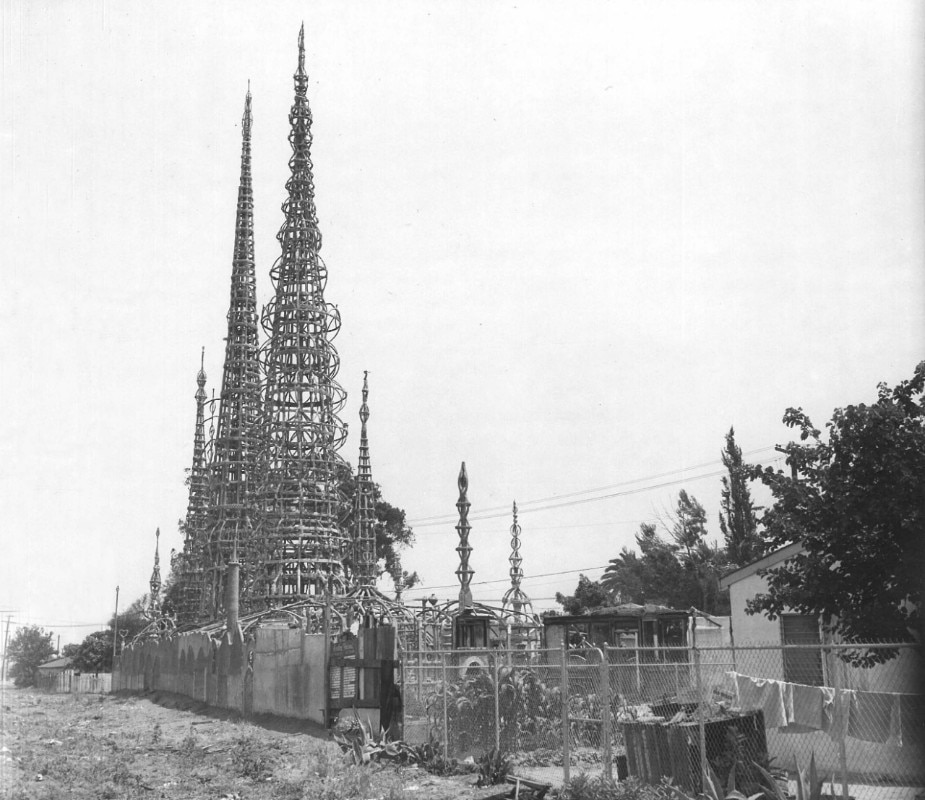

Located in the southern part of the city in an area known as Watts are the towers built by immigrant Sabato “Simon” Rodia.

They were originally known as the Rodia Towers as they were being built, and were later challenged as being illegitimate. Today, they are known simply as the Watts Towers. Rodia was born in Serino, Avellino or Ribottoli (sources vary) in Italy in 1879 and arrived in the USA in 1902, where he supported himself with various jobs at rock quarries, lumber yards and railroads.

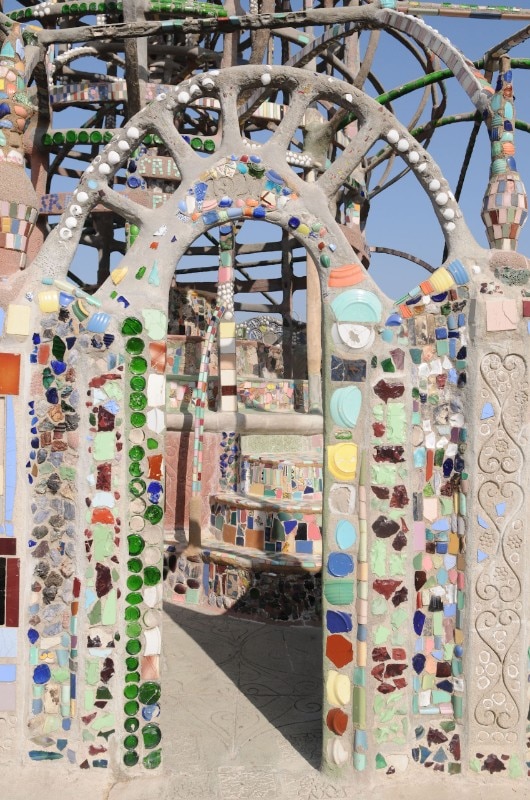

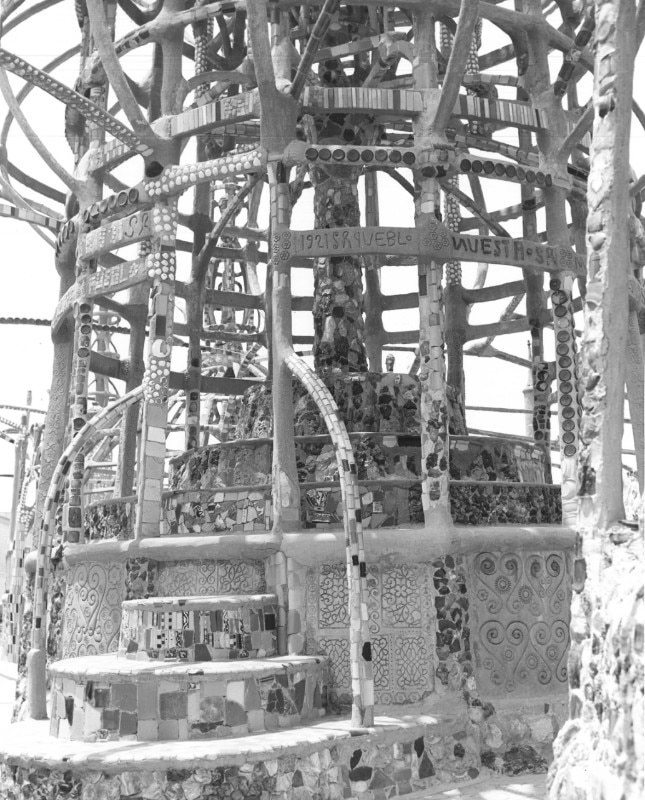

By the time he arrived in LA in 1921, he was employed as a tile setter and telephone lineman – two crafts that would be necessary to build what he called “Nuestro Pueblo”, Spanish for “our town”.

His collection of five towers were built on his triangular property, where he lived in a small house. The sculptures would rise over the next 33 years and were completed in 1954. Shortly thereafter, Rodia sold his property and left LA for a small town in Central California called Martinez and would never return.

How did he create these structures? Rodia’s answer was very simple. “I had it in my mind to do something big and so I did,” he said in a short film that was made of him and his art in the early 1950s.

The film showed Rodia collecting fragments of tile and glass for a mosaic, bending a thin piece of steel on a railroad track and climbing up one of the towers without a scaffold carrying a bucket of wet plaster to touch up part of the structure. He used simple hand tools and claimed never to have hired anyone to assist him: “I couldn’t tell anyone what to do because I didn’t know what I was doing myself.”

As to why he built them, we’re left with his notion of doing something big. An inspector who visited Rodia in 1951 described what he saw: “He accompanied us over the entire triangular-shaped property... I was more or less amazed at what he had told us at the time, how one man could do this work without assistance... He explained how he was keeping those things maintained [by] climbing up on those towers with a bucket of cement plaster [and] just patt[ing] it in place.” When asked if Rodia used a ladder, the response was that “he went up like a monkey” up the side of the tower without a ladder or scaffolding.

However amusing an image, there are photographs of Rodia at work with ladders nearby. Over time, the neighbourhood came to appreciate the sculptures as something beautiful in a part of LA that had become rundown and impoverished. But eventually, after Rodia left town, the sculptures attracted the attention of the LA government and were considered dangerous. They were too close to homes and a railroad track should they collapse in one of the many earthquakes that California experiences routinely. Because they were built without permits, the towers were deemed to be public hazards and scheduled for demolition in 1957. An organisation of concerned citizens went to court and postponed the destruction until a series of public hearings would discuss the matter.

The first issue was “what were they?” The government believed they were habitable structures like houses and were subject to the rules that defined them as such. Since no official documents permitted them, they were to be considered illegal structures. The supporters of the towers saw them as public art and, since they could not be lived in themselves, and as the house Rodia lived in had burned down after he left, they could not be defined as dwellings in any sense.

A third opinion took shape when it was agreed that a series of stress tests were needed to determine the soundness of Rodia’s construction methods. An engineer called Norman Goldstone set out to prove that the towers were closer to being aeronautical structures that could withstand any reasonable stresses.

The government brought in their own engineers who submitted documents claiming the towers were unsafe. In July 1959, scaffolds and measuring equipment were brought to the towers to see if any one of the structures could be pulled down by up to 10,000 pounds of force. A truck was attached to the base of one of the towers and the forces were slowly increased to the maximum allowed by the test. The results concluded that the towers moved less than one inch and could withstand earthquakes or high winds.

During the meetings about the fate of the towers, Simon Rodia stayed away from LA. Although notified of the city’s efforts to destroy his work, Rodia expressed no concern about their future. Whatever he had done in the past was in the past and there was no artistic expression in his new hometown. Rodia was feted by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the University of California, Berkeley for his work before his death at the age of 86.

One month after Rodia died in July 1965, the urban unrest of the Watts Riots destroyed many buildings in the Watts area of LA, but the towers were untouched. The towers are now part of a state-owned park. The Watts Towers of Simon Rodia have been recognised as artistically significant by the City of Los Angeles, the State of California and the United States government, and requests are being made for them to be designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

A letter of support to preserve the towers came from a neighbour who expressed the value of the sculptures to the neighbourhood: “Through the years, many of us old- timers watched Simon Rodia build them and enjoyed occasional evenings there admiring the play of lights on his marvellous mosaics. As a group in the lower income brackets, we have too few works of art in our midst. We would sorely miss this work of genius if it’s taken away from us.”It is to the credit of LA’s government that they saw beyond the bureaucracy and decided in favour of public art. LA is home to many myths and stereotypes but we cannot be said to be devoid of art.

Michael Holland (1961) has been an archivist for the City of Los Angeles, California, since 2010. He manages government documents beginning in 1827 to the present day. He has curated lectures and appeared on local radio and television speaking about local history. He lives near Pasadena, California.