The success of Rome is partially but undoubtedly founded on its own ruins. Ruins of more and more ancient times that, in a stratification that doesn’t compromise its monumental aspects but sometimes rather enhances them in their relation with the following ages, keeps on living today, often with little or no modification, if not conservative modifcation. A mythologised past, on which the pride — as well as the self-assurance —of the capital stands, and that, in its turn contemporary for ancient Romans, has been more than once protagonist of reinterpretations and exploitations.

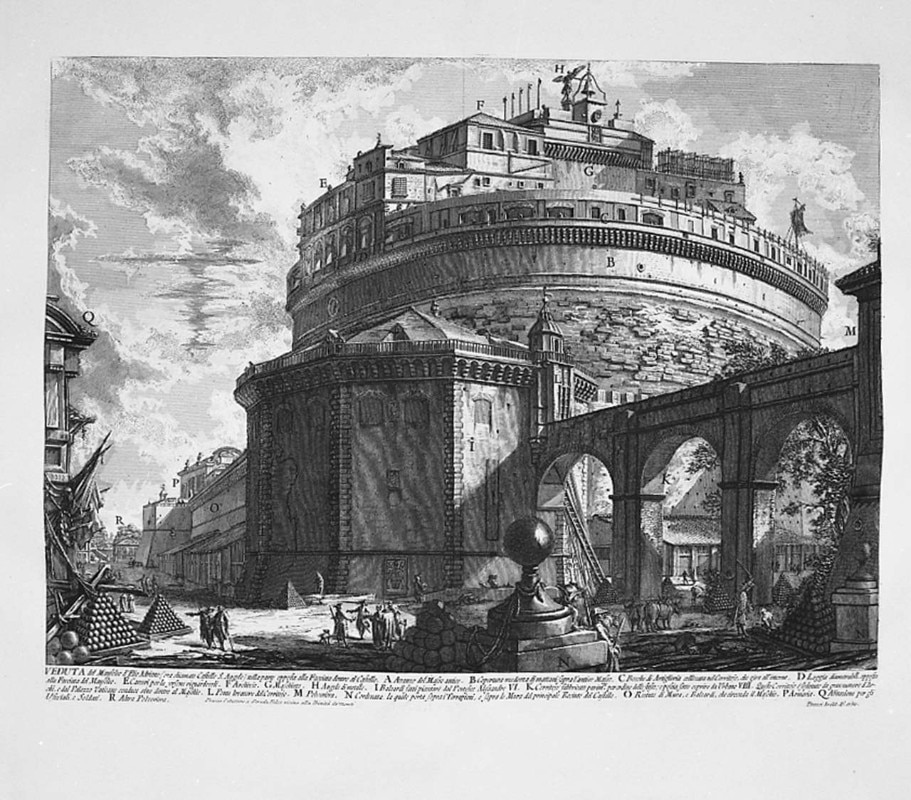

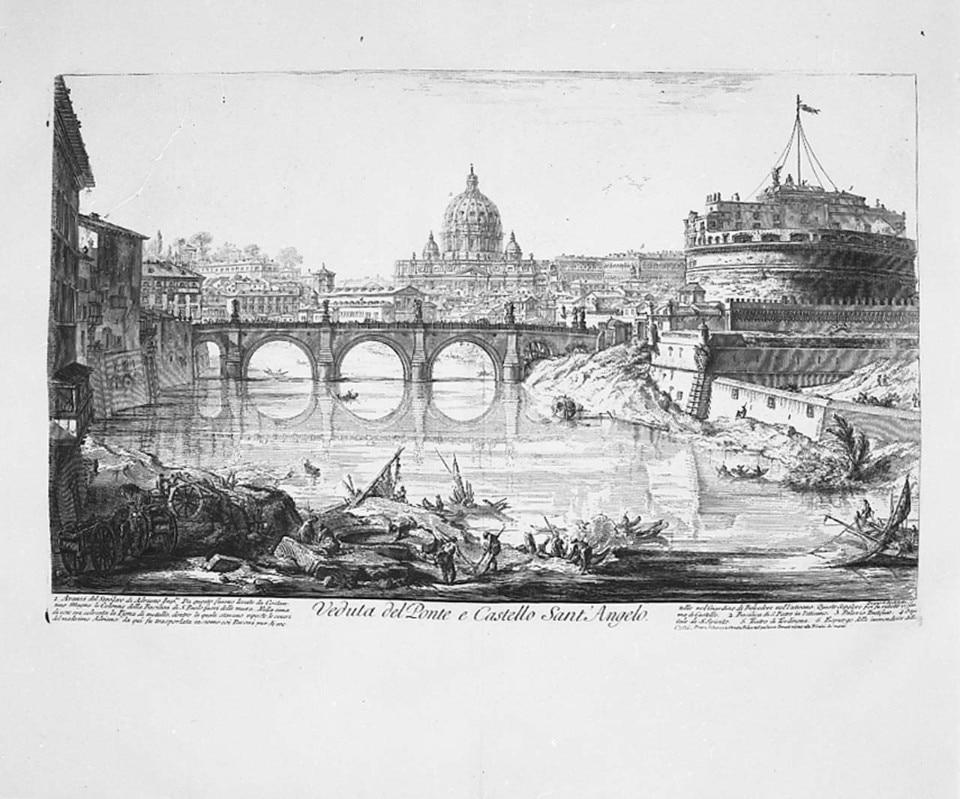

A classic performer of the reenactment of the past in a courtly and idealising declination was Piranesi, author in the second half of the eighteenth century of those “Roman Views” that provided for the perfect visual textbook to the Grand Tour practitioners.

Even if they have both been unfulfilled architects who ended up expressing themselves through art, comparing Giambattista Piranesi and Gabriele Basilico would seem ‘at first sight’ pretty odd, since besides the similarities that lie in their views (Vedutismo as a vantage point in the observation of the city) and in the common but incidental use of black and white, the unbridled fantasy and the ideological alterations of the former clearly counter the sentimental purity and the contemplative rationality of the latter.

But if on the one hand this conflict triggers a mechanism of unexpected reflexions rather than a simple short–circuit, on the other hand the two are linked by more than a merely superficial reference. It’s clear that the visual system of documentary photography — inextricably bound to reality by physical (i.e. optical and, at least once, and in Basilico’s practice for sure, chemical) but also conceptual laws — is by its very nature not able to reproduce the one of engraving, prospectically freer; but it should be noted that, even with different techniques and reasons, in a way the photographer carries on the engravers’ work.

After all, compared to the documental determinism of masters as Atget, Walker Evans and the Bechers, Basilico’s art is enriched by a quite romantic element just like Piranesi’s one, although classificatory, got rid of the weight of his predecessors’ encyclopaedism.

And it’s in the relation with the classical, on one side, and the ruins, on the other, that Basilico’s Roman views become a little summa of the milanese photographer’s work, the final and peacefully mature stretch of a path started with the industrial archeaology to come of “Ritratti di fabbriche” (1978-80), continued with “Beyrouth centre ville” (a celebrated collective work from 1991, and then, as solo, from 2003) and again with unrelated projects about cities as Arles, Bari or Palermo (2001, 2005-06 and 2007).

The result of an assignment by Fondazione Giorgio Cini via Michele De Lucchi’s intuition, dated 2010 and aimed to supplement a reach exhibition on Piranesi (interacting, although in partial display, with the engravings by the Venetian genius), the 68 photographic plates finally collected in “Piranesi Roma Basilico” (Contrasto, 2019), and presented at Museo Ettore Fico in Torino (until 14 July) together with further views of international cities, give us the chance to revive in close–up the dialogue between the two authors, comparing their similarities and differences and assessing their historical (artistic, photograpic) and Historical (humanistic, architectonic) value.

Taken, when still possible, from the same points of view of Piranesi’s engravings but, as opposed to them, devoid of whatever interpretation that could alter the sense of reality, Basilico’s photographs show as always a contemporary world, where ancient Rome’s remains once ruined are now monuments, and the architectures that once where state of the art have become classical heritage. The only thing that hasn’t change is the human presence, the hineritors of those early tourists that today, in different clothes and countless amount, still inhabit the streets and squares of Rome just like in those 18th–century engravings: a real trait d’union between past and present in a just apparently unchanged scenario.