A book about the secret beauty of Bogotà as a gift to his Colombian adopted daughter once she’s older. A fashion magazine that actually shows the space separating Paris and Minnesota, and the one between the photographer and his subjects as well. A newspaper that reports the disenchantend on–the–road chronicle of the eight years long Bush administration across the United States. A manual on and for people who want to avoid or have escaped civilization, hidden in the carved pages of an unsuspecting book. An album of (self) portraits realized in Tokyo during a five–day commission from the New York Times without even leaving his hotel room.

It’s fifteen years now that Alec Soth has been sistematically kept on surprising and decoying his followers with unclassifiable works, by his own ammission dealing with subjects and telling stories in far and different ways from what one could expect from Magnum, «a well–known photo agency often associated with war photographers» that he joyned in 2008.

With his last work, Soth pushes again the boundaries of documentary photography, trespassing the more and more imaginary line between particular and general, private and public.

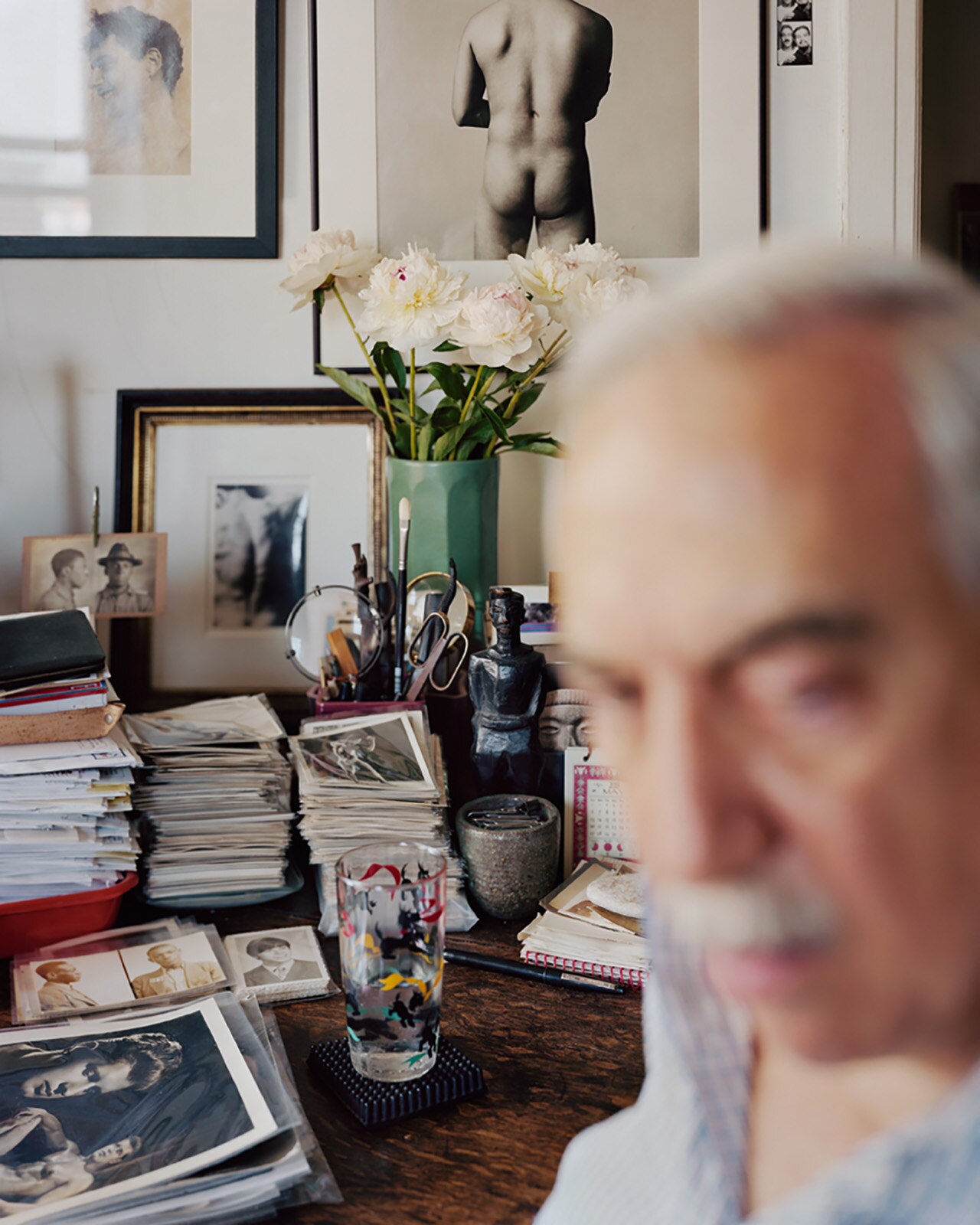

Published by MACK, and exhibited at the same time in Berlin, Minneapolis, New York and San Francisco, “I know How Furiously Your Heart is Beating” takes its title from a poem by Wallace Stevens. Soth once again moves through the awareness of the space that divides / bonds two separate egos, — the photographer’s and his subject’s ones, in this case — a recurring theme of the american poet.

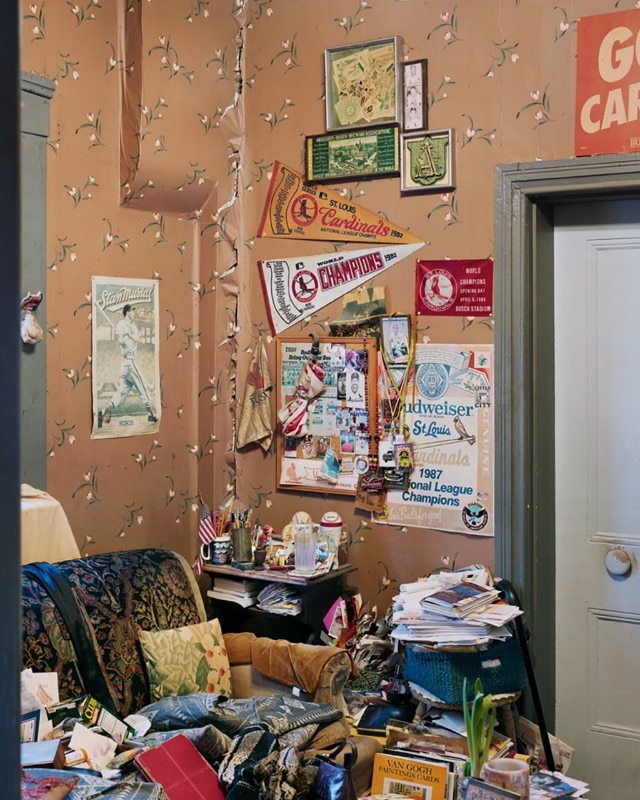

For one year he has been asking perfect strangers to be allowed into their houses, in that private and specially personal dimension we generally never share with someone who doesn’t belong to our circle of friends and close acquaintances, thus putting himself out of his own comfort zone, in a photographic place paradoxically more dangerous then a war scenario.

A tension is then established in the dialogue and confrontation between the watcher and the watched, but as opposed to the theatrical drama it sometimes seems to refer to, it doesn’t resolve within the frame of the picture but gets pass its edges, maybe even persisting in the rooms where it first generated, and for sure in the eyes of the amazed viewers.