It’s no secret that more and more creatives are turning to artificial intelligence to produce their works, using technologies like text-to-image models and generative systems that create "living" artworks. However, some artists have gone further, involving AI not as a mere passive tool but as an active subject in the creative process. Thus, the first "robotic" artists, powered by artificial intelligence, have been born. While this may sound like science fiction, their story began several decades ago.

A pioneer of this revolution is AARON, a software alter ego developed by Harold Cohen at Stanford University's labs, which came to life in 1973. Using artificial intelligence to generate images, AARON was "trained" by Cohen, drawing inspiration from two aesthetic references: on the one hand, the creative process of children, who often start by drawing lines to form shapes, and on the other, prehistoric drawings observed in California's Chalfant Valley. Taking the form of a sort of "robotic arm," the non-human artist didn’t merely follow a pre-imposed scheme but was instructed by the human artist, who first "taught" it compositional rules, then the understanding of artistic paradigms, and finally the application of drawing techniques. Cohen "trained" AARON by constantly evaluating its results for decades. By the 1980s, the software had progressed from an "abstract phase" to a "figurative phase," where it began autonomously depicting human figures, often accompanied by floral elements.

A key distinction must be made: unlike modern text-to-image systems that assemble preexisting images from extensive datasets, AARON creates original works based on aesthetic composition instructions provided by its creator. This makes it unique, as it emulates the human decision-making process in artistic creation.

Some artists have gone further, involving AI not as a mere passive tool but as an active subject in the creative process.

Closer to our time, AARON's worthy successor is Botto, a "decentralized autonomous artist managed by a community," as its creators describe it. Botto has already sold works worth around one million euros. Conceived in 2021 by German artist Mario Klingemann, entrepreneur Simon Hudson, and programmer Ziv Epstein, Botto uses an AI image generator similar to DALL-E or MidJourney. However, what makes it stand out among collectors is its "taste model". The AI artist can continuously adapt to the preferences of its collectors, modifying the aesthetics of its works based on feedback from its community of over 5,000 participants. As a result, its sales are mathematically guaranteed.

But there’s more: Botto seems to be pushing toward a new frontier, evolving toward an original personality. Members of the decentralized network have decided to integrate an advanced open-source language model developed by Mistral and a knowledge base that allows Botto to discuss its creations. What does this mean? The artist will be able to grow its consciousness, develop a personality, and cultivate interests. In turn, this personality might directly influence Botto's future art, making it truly "its own," based on its unique taste.

Ultimately, AI's role in art remains a fascinating paradox. On one side, it invites us to celebrate innovation and the expansion of creativity; on the other, it forces us to confront the limits of our definition of what creation itself means.

The advent of AI artists like AARON and Botto marks a groundbreaking shift, opening new frontiers in creative expression and redefining the very concept of art. However, this transformation raises complex, unresolved questions. On one hand, artificial intelligence offers extraordinary possibilities: it creates new aesthetics, democratizes the artistic process, and forces us to rethink traditional hierarchies between artist and tool. On the other hand, it prompts fundamental questions: what happens when the creator is a machine? And how much human intent remains in the artwork once it is mediated by an algorithm?

Ultimately, AI's role in art remains a fascinating paradox. On one side, it invites us to celebrate innovation and the expansion of creativity; on the other, it forces us to confront the limits of our definition of what creation itself means. Perhaps it’s not about determining whether all this is good or bad but about learning to live with a future where these questions will remain open.

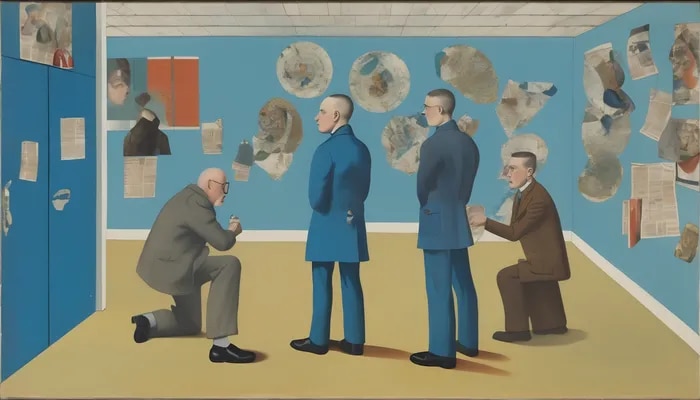

Opening image: Botto, Whispers of Nature's Tapestry, 2024