This article was originally published on Domus 1092.

Growing up in the Britain of the 1940s and 1950s was full of contradictions. The country had been shattered by war and its leading role in global political affairs was being eclipsed by America and the Soviet Union. At the same time as its people were enduring rationing of the most basic daily goods, it was building a model welfare state. In parallel, the nation’s industries were making huge technological leaps forward – radar, computing, the first passenger jet engines and airliners to name a few.

A cycle ride I took from my home through Manchester’s Lowry-esque industrial hinterland into rural Cheshire to visit the magnificent new Lovell radio telescope at Jodrell Bank encapsulated the Janus-faced nature of post-war Britain. What would now be termed austerity was a way of life that was normal at the time, which made optimistic visions of the future even more glamorous and desirable. Like so many of my generation, I found all of this, and more, in the pages of the Eagle magazine.

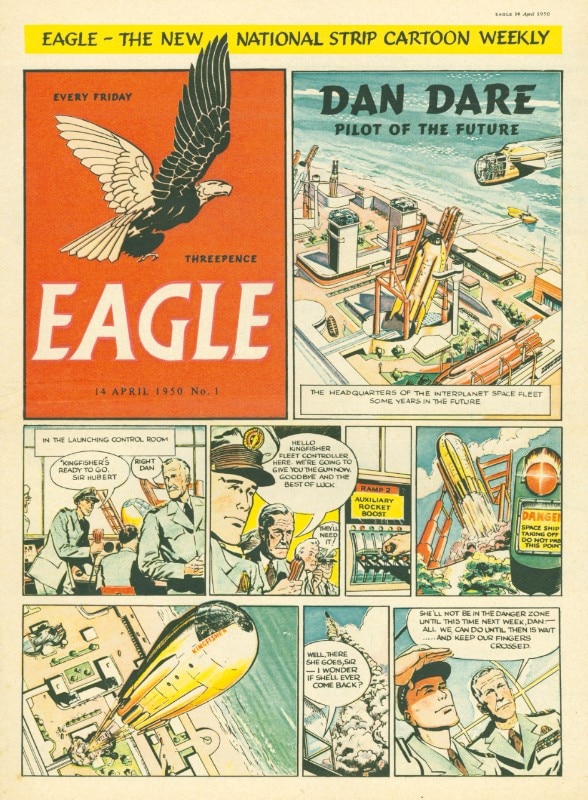

Launched in 1950 by Marcus Morris, a Methodist minister, and illustrated by the great Frank Hampson, Eagle sold nearly a million copies of its first issue. Manchester-born space pilot Dan Dare may have been the front-page hero, but it was the information-filled pages inside that excited my attention. The vision of the unimaginably far-off next century replete with sleek skyscrapers, vast gleaming domes, monorails, and teardrop-shaped cars and rockets was thrilling. I was moved by the glass-and-steel fantasies that might now be labelled high-tech. But this only tells half the story.

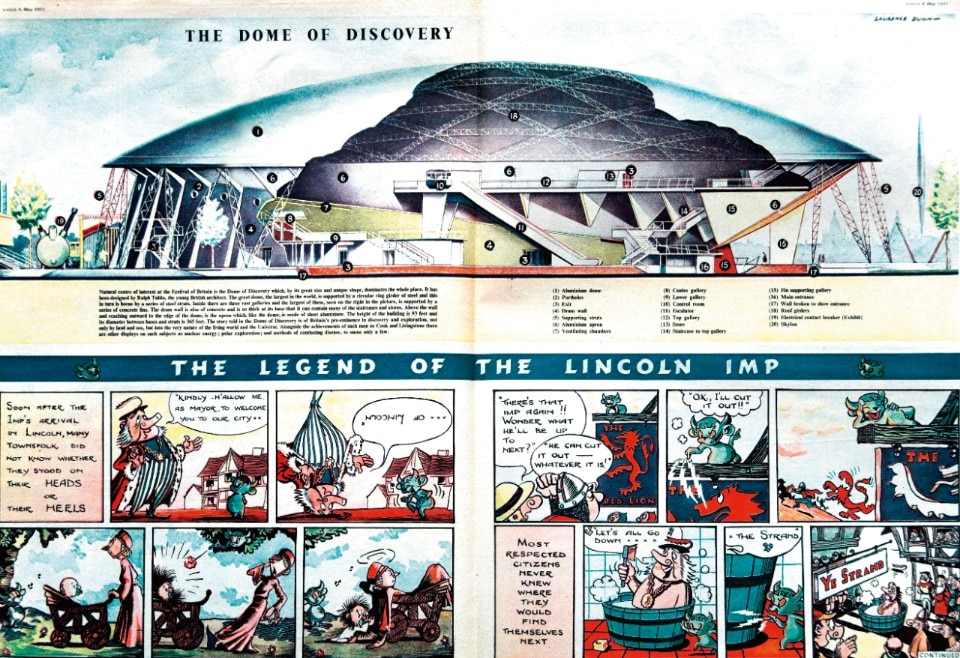

My weekly dose of the Eagle was not complete until I had marvelled at the extraordinary cutaway drawings on the centre pages of each issue. The graphics brought the here and now to life as well as the emerging new technologies. The nuts and bolts of jet aircraft, power stations, swing bridges, locomotives and world speed record cars were drawn out in meticulous detail. These graphic peeks under the skin of machines were my introduction to construction technology, and in the case of the 1951 cutaway of the Dome of Discovery, to modern architecture. As givers of insight, the Eagle’s cutaways are masterpieces. They are also to my mind works of art in their own right.

The love of technical drawing they inspired has never left me, and I was delighted to connect with John Batchelor, one of the Eagle’s team, and commission a cutaway drawing of my practice’s Renault building. It was published under the apt title The Eagle has landed. My love affair with the Eagle is of course by no means unique. King Charles III was a fan and Stephen Hawking credited it for his interest in cosmology. It even managed to be the first publication to print a work by David Hockney. We see its influence in the work of Archigram in the 1960s, in a whole generation of British architects in the 1970s, and more broadly in the emerging city skylines of Asia. The Eagle’s unique combination of an optimistic vision of an exciting and better future, and a deep technical understanding of how things work and fit together inspired a generation and continues as a reference point from my past.

Opening image: Cover of the first issue of Eagle, which hit newsstands on 14 April 1950. The publication ran from 1950 to 1969 and, in a relaunched format, from 1982 to 1994. Photo © Retro AdArchives / Alamy Stock Photo