The grandiose rooms of the venerable London institution are hosting a display of luxury inspired by Bill Viola this is elementary in its educational approach. Basically, it is a perfect marketing manoeuvre.

This was my first and also my final impression when I exited the semi-darkness and returned my gaze to the light. The juxtaposition of the two artists – the former complete with name and surname, and the second using just his name, confirming his established presence in the shared culture of the West and therefore a must-see – works perfectly, at least in marketing terms. It is clearly an operation combining a contemporary-art audience with that of old art, thus guaranteeing larger visitor numbers. However, on observing the public move around the rooms, few of those who stopped before the Michelangelos, wearing glasses or holding a drawing pad, paid as much attention to Viola’s videos. Of course, a small Michelangelo drawing does not require the same time as a video, at least a video more than a couple of minutes long.

Nevertheless, the exhibition is a luxury. It is a luxury to see the drawings owned by the Royal Collection Trust, the foundation of the British Sovereign, and bears with it a sense of wealth that reverberates onto the visitor. Indeed, it was a visit made by Bill Viola to the collection that first inspired the idea of the exhibition. It must also be said that not every day can you see such drawings – all elegant, some dramatic as in The Lamentation over the Dead Christ (1540 c.) and others joyous as in The Risen Christ (1532-3 c.).

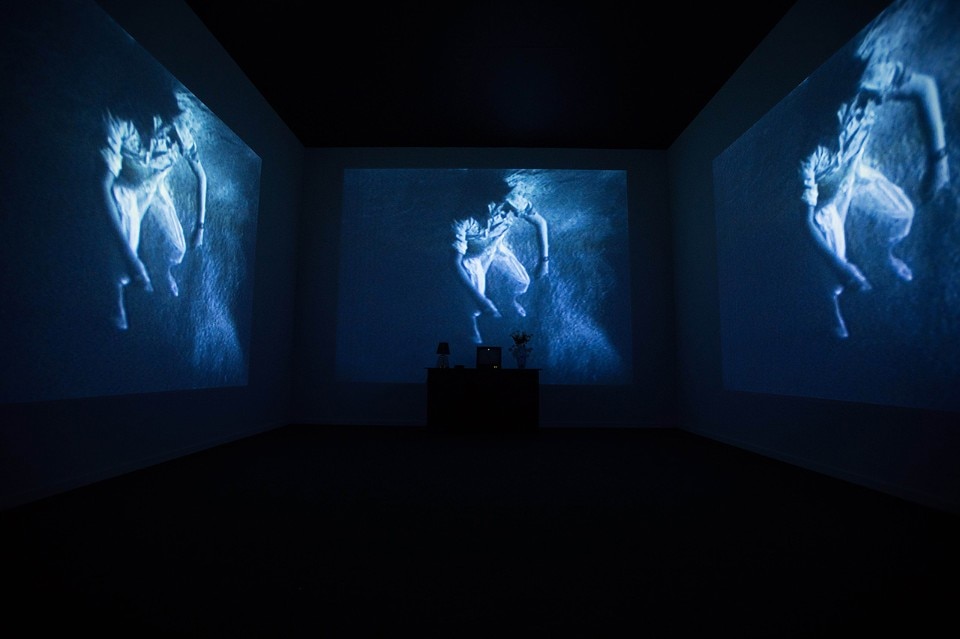

The central room where Viola’s Nantes Triptych (1992) comes face to face with Michelangelo’s Taddei Tondo (1504-5) is the key moment of the exhibition and validates the “Life, Death, Rebirth” subtitle.

The famous video triptych – in which a woman giving birth in the first picture conveys the intense exertion of giving birth sits alongside the second where life is an indistinct figure visible in the water and then the third, in which the artist’s mother is dying – looks straight at the splendid Tondo. On entering the room, your gaze is inevitably drawn to the strong, luminous and large video. Then, a turn towards the Tondo, owned by the Royal Academy, produces the desired effect: Michelangelo is reassuring in the tender portrayal of the relationship between mother (the Virgin Mary) and child. Herein lies the trick and old art wins one-nil. I had studied the Tondo in a black and white photograph just a few centimetres in size that made it look old but it is contemporary as only white marble can be and, had the exhibition design by London studio Carmody Groarke not prevented me from doing so, I would have touched it to feel that matter, polished or rough-hewn.

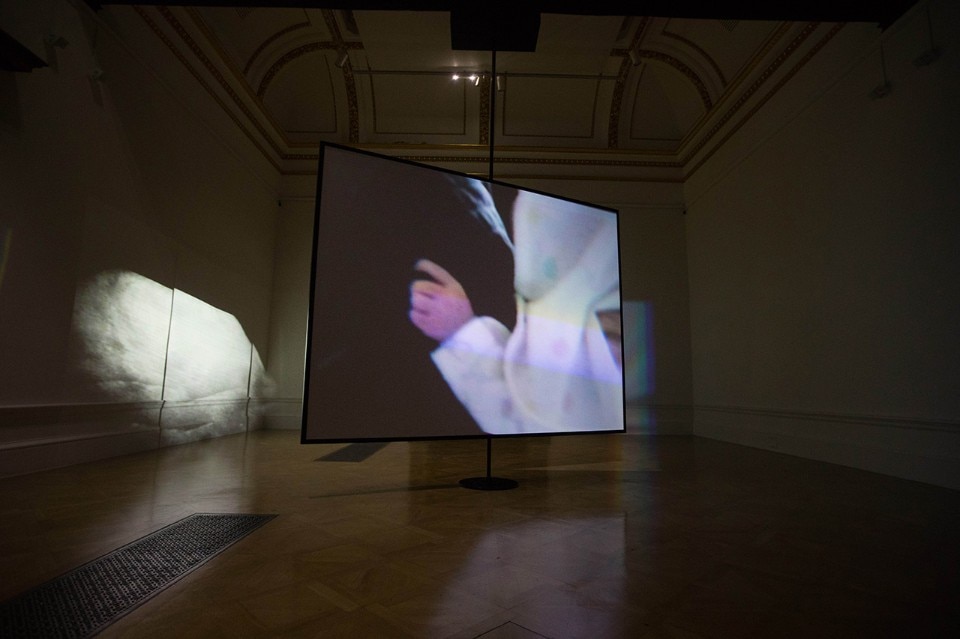

Farther on, the last video installation The Dreamers (2013) features seven people lying beneath the water’s surface that represents all humanity; and it gets you. Slowly, you realise they are alive but also perhaps dead, and certainly suspended in time. The spirituality they represent however has something aesthetic and vaguely prissy about it, like John Everett Millais’s splendid Ophelia (1851-52) to which it refers, not the ambiguous Shakespearian figure, the young woman who loses her mind, but his “redesigned” version.

As I was saying, the educational intention is elementary. If it is true that museums, all of them, are forced to chase turnover then the juxtaposition explains why today’s artists do not spring up like mushrooms but are bound to the history of art; they descend from it.

This ought to be obvious to each visitor, were art not sheer entertainment. After all, Viola became involved with old art starting from The Greeting, presented at the 1995 Venice Biennale and manifestly inspired by Pontormo’s Visitation (1528-30). Back then it left us all speechless in its totally new approach to the video work.

- Exhibiton:

- Bill Viola Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth

- Until:

- 31 March 2019

- Venue:

- Royal Academy of Arts, Londra

- Set design:

- Carmody Groarke