“I’m a generalist,” David Bowie said of himself to Rory MacLean, an assistant on the set of “Just a Gigolo”. What he meant was that he saw himself as a Renaissance man, multifaceted and eclectic. He returned to the topic on other occasions, as in an interview from his Diamond Dogs era: “I’m only using rock’n’roll as a medium (...) I wanted to be the instigator of new ideas. I wanted to turn people on to new things and new perspectives. I always wanted to be that sort of catalystic kind of thing.” David Bowie was universally known for the range of his involvement with culture and forms of artistic expression: he was not just a rock star, but also an actor, a mime artist, a painter and an art critic – among other things. He was engaged with visual art almost as much as he was with music and words. It’s no surprise then, while it was the Beatles who gave the promotional video a cinematic grandeur by hiring Richard Lester, Bowie was one of the first to make the music video a standalone art form. Here are five key videos from the career of the Man Who Fell to Earth.

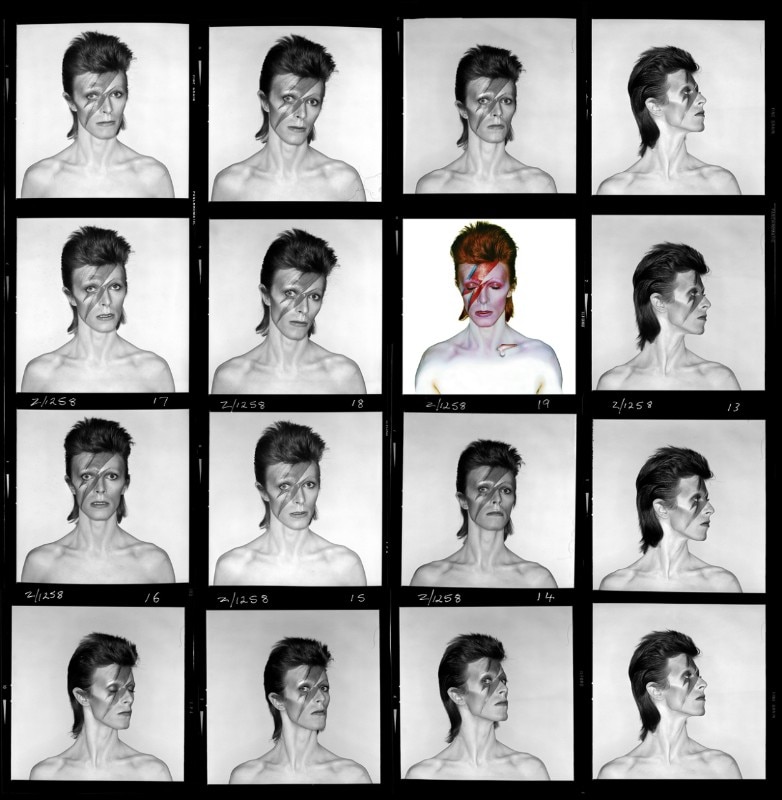

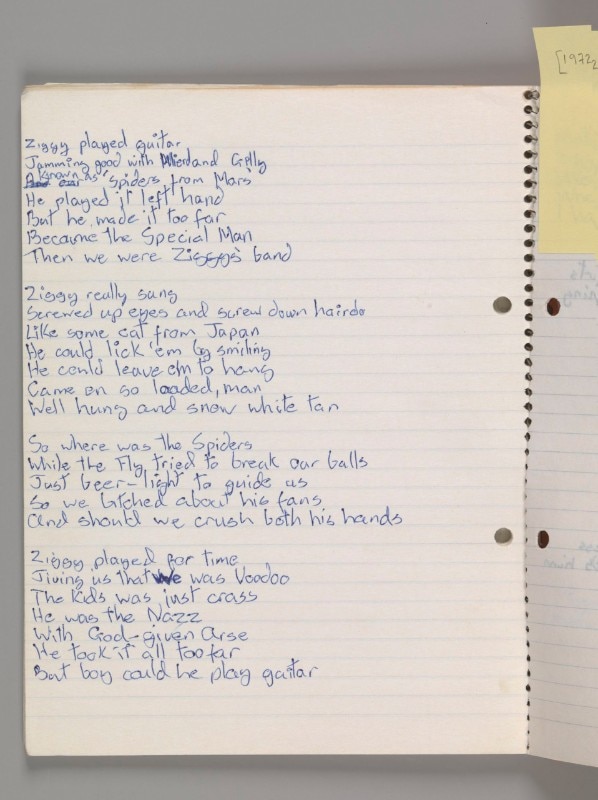

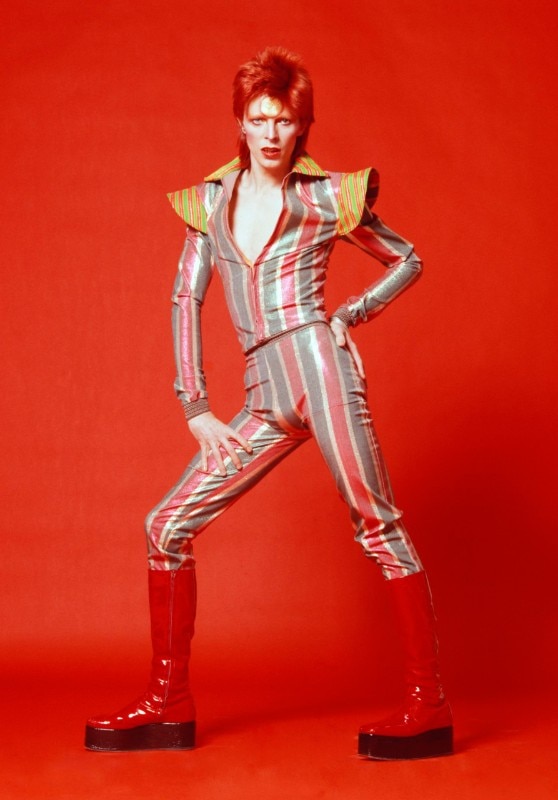

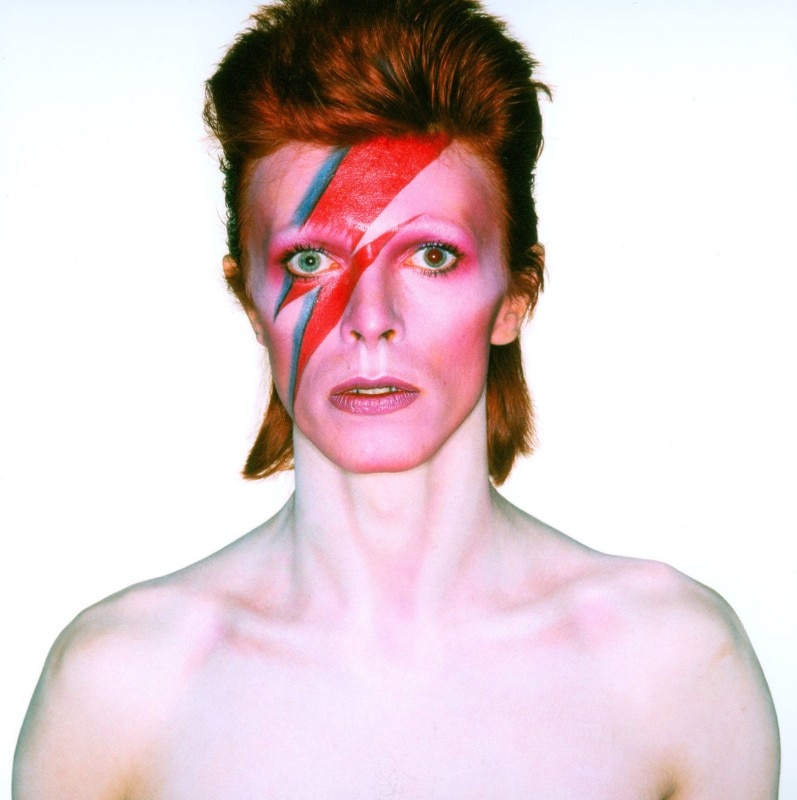

Starman (live at “Top of the Pops”, 5 luglio 1972)

This was not just the launch of Ziggy Stardust – the bizarre androgynous alien who had landed on the stage in a rainbow jumpsuit – and his creator’s career as a superstar, it was a call to arms. Many remember feeling that they were being personally recruited when Bowie looked straight down the camera, pointed with his finger and sang: “I had to phone someone so I picked on you.” A simple gesture, the arm lightly placed around the shoulders of the guitarist Mick Ronson, had an impact that is impossible to appreciate in our post-sexual times. Six months after the famous NME interview in which he declared, “I’m gay”, it was a deliberate challenge to a Britain that was still post-Victorian. Homosexuality had been decriminalised only five years earlier, a move that split the country, scandalising one half and liberating the other. It was a polarising performance, one that used spectacle and glam rock to create a field of political activism that was light years away from the ideology of ’68, but was just as radical, detonating the fault line between the young and the old and their opposing views of art and morality. The sexual was only one of many identities that were subverted and transmuted into forms with more porous boundaries. Needless to say, in the space of a few months, even heterosexual miners began to visit their locals in make-up, wedges and feather boas.

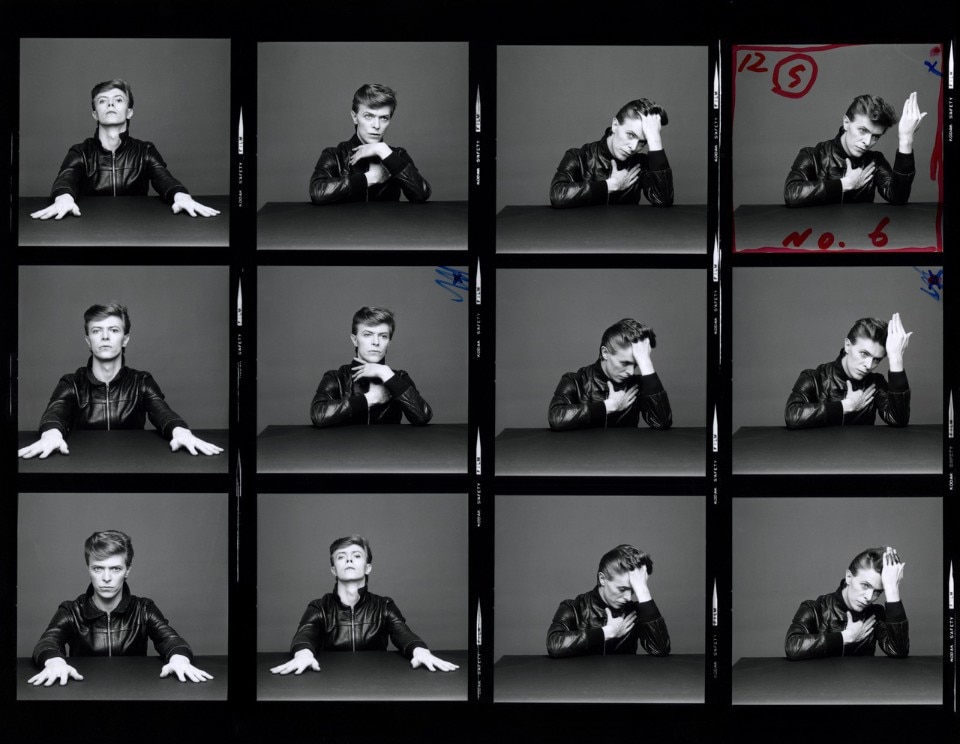

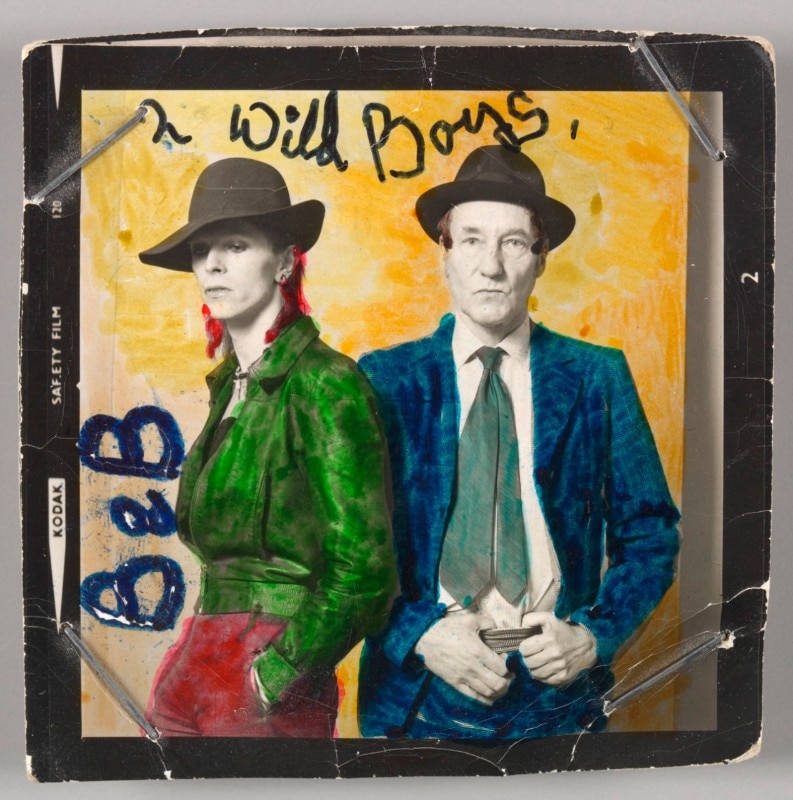

Boys Keep Swinging, regia David Mallet (1979)

Here we’re in the most adventurous, most seminal period in Bowie’s career: the Berlin Trilogy, from which flowed almost all the music of the following decade. The album is Lodger, an underrated masterpiece with a picaresque, futurist tone. The video for “Boys Keep Swinging” is an apparent half-return to order after the sparkling images of his glam rock period. Compared to the second section of the video, where Bowie appears in drag as the three ages of woman – impersonating a Berlin cabaret singer – the first section appears like more a traditional performance to camera. David is styled like a mod and the video is dynamic, alternating close-ups with shots of the whole stage. Nothing happens, but the gestures, moves and expression are magnetising and mesmerising. No one filled the stage like David Bowie, no one had his charisma.

Ashes to Ashes, regia David Mallet (1980)

This is probably his most famous video – the one which summed up the Bowie paradigm. All the recurring elements in his work are here: the experimentation with technology (the colour inversion using the Paintbox technique), the use of disguise (the Pierrot costume from his Scary Monsters period) and the favourite themes (alienation and the correlation of cosmic space, the hybridisation between the technological and the organic, the predictions of a violent future evoked via ritual, and mental illness). There are references here to H. R. Giger, Albert Camus and Lindsay Kemp – one of many examples of the intellectual unscrupulousness and eclecticism of David Bowie, that most cultured of rock stars.

The Heart’s Filthy Lesson, regia Sam Bayer (1995)

Directed by the filmmaker who made the classic 90s video, Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit”, “The Heart’s Filthy Lesson” introduces us to the world of Outside in an atmosphere that is half Hermann Nitsch’s Orgies Mysterien Theater and half Joel Peter Witkin’s photographic vision. Bowie oversees the assembly of a Minotaur in a continuous glissando from body art to body horror, the chorus reflecting the themes of the album and the hypertextual story that completes it: the narrative of the murder and ritual dismembering, “for artistic ends”, of the 13-year-old Baby Grace. As the new millennium approached, Bowie picked out a subterranean current of neo-millenarianism and the return of primitive, ancestral rites based on death, violence and chaos, enabled by the internet and technology heralding the death of authority and hierarchy, and the promise of an eternal present.

Lazarus, regia Johan Renck (2016)

Here we’re at the very last of Bowie’s videos. “Lazarus” was shot in New York in November 2015. A few hours earlier the doctors had told Bowie, who was suffering from liver cancer, that there was nothing more they could do. “Lazarus” would be the Thin White Duke’s last work of art, and he would leave his home only once more. On 8 January 2016, his 69th birthday, Blackstar was released. The video for “Lazarus” had appeared a day earlier. On 11 January, the world woke up to shattering news: David Bowie was dead. It’s easy to see the images in his last video as a metaphor for death. Yet it seems that the idea for the final disappearance into the wardrobe came from someone on the set – it’s unclear who. The story is that Bowie grinned and said: “Yeah, that'll keep them all wondering, right?”