This is the most comprehensive exhibition of her multidisciplinary and committed work, presented in the form of a work-in-progress offering paths, perspectives and ideas, not in chronological order but infused with a diffuse and timeless synesthesia. A fragrant 2200 blocks of olive-oil soap form Present Tense, 1996/2011, channelling and recording information on the dismemberment and return of the occupied territories.

Its design is based on the 1993 Oslo Accord between Israel and the Palestinian Authority, a piece of recent history the contours of which look like a constellation of islands with liquid boundaries, traced by tiny red-glass pearls. Those who have forgotten her more strictly political beginnings are served up the material from her first performances of the late 1970s and her 1980s video works. If the word “political” still retains any meaning, Mona Hatoum has turned her work into a criticism of social control and a permanent trademark.

The distances within the artist’s work really do appear incommensurable, poised between the Franciscan simplicity of Roadworks, made in the London neighbourhood of Brixton and the scene of racial clashes, in which the artist dragged a pair of Dr. Martens behind her in 1985, to the elegant Cellules, 2012, steel cages containing drops of blown glass resembling organs abandoned by bodies in transit through a devastated present.

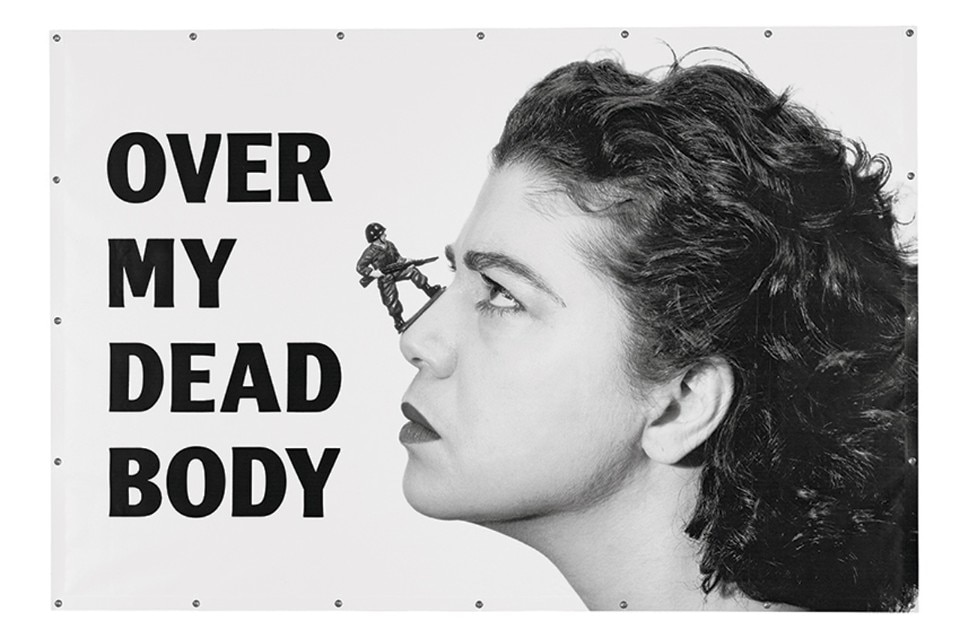

Hatoum offers contemplation but also a potential way out, doing so via the skilful use of Post Avant-Garde languages, from minimalism to conceptualism. Experience gained and refined during the years of her forced personal London diaspora and those of her artistic residences has taken her to the key locations of an art that was becoming global, and to museum collections and biennials at a time when there was still space for reflective artists.

The daughter of the head of Lebanese customs, Mona Hatoum divides her time between London and Berlin and holds a British passport. When blocked by the civil war in a pre-Thatcherite London, she developed all the antibodies of an artistic fabric that reacts to surges of free enterprise.

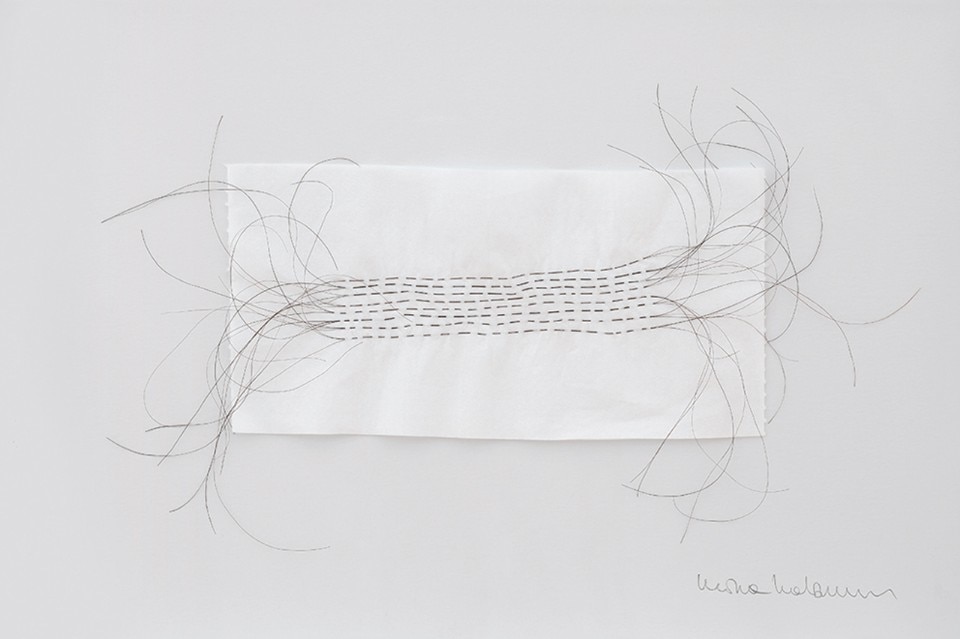

Her eye is always focused on everyday objects which are transfigured by the Surrealist drive to recreate a domesticity of discomfort, instable means and genres: from barbed wire to pubic hair passing via test tubes and a whole repertoire of resistance stories and images. Even her Hanging Garden, 2008–2010, on the terrace of the Centre Pompidou is built out of the sandbags that appear everywhere in daily life during times of war but the grass growing on them offers the potential for rebirth and a conflict-free world, or at least one where conflict only spawns positive change.