Cauleen Smith: I became obsessed with one specific Sun Ra composition: An eccentric little song called, Love In Outer Space. I really loved the song and decided to find out who this composer, Sun Ra, was and why was he so obsessed with all galactic things. Very quickly I learned that Sun Ra developed his persona (among other things, he claimed he was from the planet Saturn very early to the day he died) while living in Chicago between 1945 and 1961.

This was intriguing because within American popular culture, Chicago is a city that routinely produces creative giants. I became curious about what it was about the city itself that made it such an incubator for experimental creativity. And I wanted to make some kind of creative work of my own that celebrated the lucky intersection of Sun Ra and Chicago and the period of time that he spent there.

Paola Nicolin: You addressed Sun Ra as a person rather than a myth: which is the role and the use of archives in this context of research?

Cauleen Smith: Yes, there are two significant archival holdings of Sun Ra and his business manager, Alton Abraham’s personal papers and audio recordings located in Chicago. Holding personal items like cancelled checks, hand screenprinted album covers, cassette recordings of radio programs in my own hands, it altered my relationship to this person and his creative work. I shifted from thinking of him as a curiosity and a historical figure, to a dedicated creative thinker and cultural producer. I recognized strategies that he used to make his work and to direct his Arkestra, that I could relate to as a filmmaker. Also, I began to see that improvisation was a very central part of his discourse with his musicians and in his compositional process and I admired that. It is difficult, sometimes, when working with a film production crew to improvise at all.

I wanted my films to have the power and unregulated innovation that improvised music has. And so I decided to take what I learned from the archives and try to put these things into practice. I pressed records, and hand screen printed album covers, and worked with a large band, and cajoled people into wearing crazy costumes – lots of crazy stuff. I wanted to see how these tasks would influence the moving images I made, or how loosely but intentionally I could make a moving image. I learned a lot from the process.

Paola Nicolin: The narrative of the work is – also – a quite interesting aspect of the work. How did you develop it?

Cauleen Smith: A constellation of fourteen films comprises the full-length movie, The Way Out Is The Way Two. Because the films were conceived for an art exhibition space and not a theatrical film environment, I settled on a structure that would enable a spectator to feel as if she could have a complete experience without actually watching the entire eighty-two minute piece. Moreover, I allowed the subject that I was filming to determine the form of the film instead of imposing a uniform standard of aesthetic rules across the entire piece. It was my hope that if a spectator accumulated viewings and watched more than one short, then some clear conceptual threads, characters, and narrative arcs would emerge.

Paola Nicolin: An issue of the work I think is also the idea of a city as an inner-space, and often the work is described as a psychogeographic film. The film produces subjectivity about an urban context like Chicago: is it so?

Cauleen Smith: I like this idea of a city as inner space. You know cinema has such a love affair with urban spaces. But usually the city is used as a stage, as a backdrop, occasionally a director will conceive of the city as a character, and this city-character acts upon the narrative. But to think of a city as inner space, as something that could be inside of a person who lives in the city as well as the landscape around a person offers the possibility to investigate interiority — and the ways that we engage our environment and allow it to teach us things about ourselves.

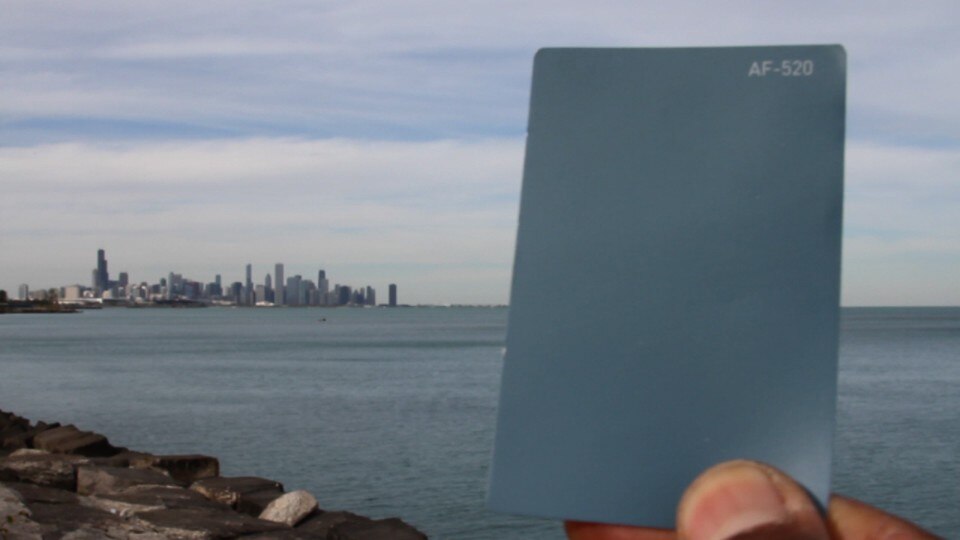

As I investigated Sun Ra’s life, I personally began to feel that Chicago was inhabiting me as much as I was exploring it. Mundane elements, like man hole covers, or elevated train platforms take on mystical, playful, historical significance, depending on how each particular film engages the city. You know Chicago is very segregated. Ways of life in the city are determined by which ward or neighborhood one inhabits. But what I learned from trying to make films about the way Chicago was inhabiting me, and speculate on how it might have inhabited Sun Ra became images that seem to intersect with human experience with cities on a very broad level. Perhaps through movies we can share subjectivities.

Paola Nicolin: The work seems an articulated combination of improvisational music, procession and public disruptions, and it affects a lot on the idea of how to think about public space. Is there any discourse on public space in the work?

Cauleen Smith: The very last film that plays in The Way Out Is The Way Two, was the first film that I made. The process of producing that public procession / disruption / flashmob combined with digging into the Sun Ra archives really sent me deep into the psychogeography of the city. Before taking on this project in Chicago, I’d been making a piece in New Orleans. This is where American brass band culture was really born – through the innovations of the likes of Buddy Bolden, Louis Armstrong, and then later brass band crews like The Dirty Dozen or Rebirth Brass Bands. When you see a New orleans Brass band take over a street (when it is not Mardi Gras), it’s an amazing experience because usually, the event is not sanctioned by the city. The musicians, frequently celebrating some event in their community play publicly, inspire of threats of arrest or sanction.

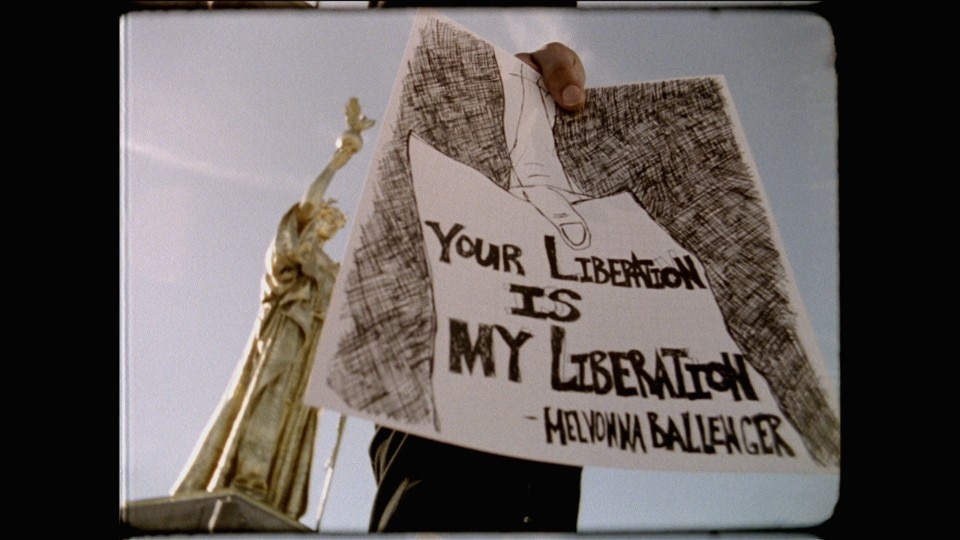

So the very act of making music publicly becomes a form of protest while simultaneously being a celebration. I think this is a brilliant tactic for disruption. If the protest is so tantalizing and pleasurable that shutting it down would backfire, then the people have really found a way to make space for themselves! Also public spaces are only as public as the government decides they are. If The People want to claim, or reclaim, their public spaces, or inhabit spaces in which perhaps may not always feel welcomed, then what better way to do that than through a imposing a huge bombastic marching band into the space, just long enough to interrupt the mundane course of everyone’s day but not long enough to cause harm or escalate conflict.

In my film, a high school marching band, very respected for their musical and performance prowess, plays an arrangement of Sun Ra’s Space Is The Place in Chicago’s Chinatown Square. The kinds in the band are from the Far Southside. It would be a rare opportunity for them to hang out in Chinatown. The vendors and workers of Chinatown would not have any need to go southside and therefore may never get to enjoy the amazing experience of hearing this band. The flashmob – sending the marching band into Chinatown square, was a gift and a challenge – a celebration of both cultures, and a protest against segregation. The pouring rain just made amplified the intensity of the experience. Space is the place.

Paola Nicolin: What does black imagination mean to you? Can we discuss about this work also in this term?

Cauleen Smith: I use black imagination to describe the radical potential of black people to imagine and describe themselves rather than accepting the designations and description imposed upon us. This idea has extended, now, to the various forms and structures of my work where rather than conforming to classical notions of narrative, aesthetics, and style, I allow my subject matter to show me what is possible. The subjects actively shape the film. I do not want to mold people into passive objects to be filmed.

Paola Nicolin: Can you tell me which are your source of inspiration in relation to Afrofuturism researches?

Cauleen Smith: I reference a wide range of filmmaking strategies within the various films. The little girl in a cape spinning is a direct homage to a classic early video work by Dara Birnbaum, Wonder Woman. In terms of music, the sounds I found in Sun Ra’s archive really blew my mind. I used as much of it as the Archivist would allow. So the sound in the film with the spinning girl, is just this amazing clip of Sun Ra jamming the piano while his Arkestra holds down the form of the song, The Sound Of Joy. It’s an amazing improvisation he does – so tantalizing that I did not want images to distract, thus the repetition. I think I was thinking of a little known Scottish filmmaker named Margaret Tait when I made the film of the kids in superhero capes riding bikes and playing on the beach of Lake Michigan. I think of her as a pastoral cinematic poet. I was interested in the ways that urban kids engage the natural world and the ways the natural world infuses the imagination of children. But I think there is also a sadness – or maybe a tenderness – there of their vulnerability. This is a sensation that emerges a lot in post-apocalyptic films.

There is a film, Strelitzia Mediation, in which I improvise flower arrangements (ikebanas) using the Bird-of-paradise flower. I started doing these flower arrangement films after spending quite some time admiring Bas Jan Ader’s work. He’s not really a popular guy in afro-futurist circles, but he is one of my favorite artists. These three examples, I think, really capture the range of tactics used to make the films: structuralist, formal, performative, narrative, documentary. And yet all of those tactics are pushed through a rubric of improvisation, and responding to sound and music quite specifically. Afro-futurists are such nerds that our references don’t even fully align with what one would consider science fiction. But some direct references might be Lizzie Borden’s Born In Flames, John Sayles’, Brother From Antoher Planet, and of course Sun Ra’s own Space Is The Place.

Cauleen Smith (Riverside, CA, 1967) is an artist and filmmaker interested in documentaries and the potential of experimental films.