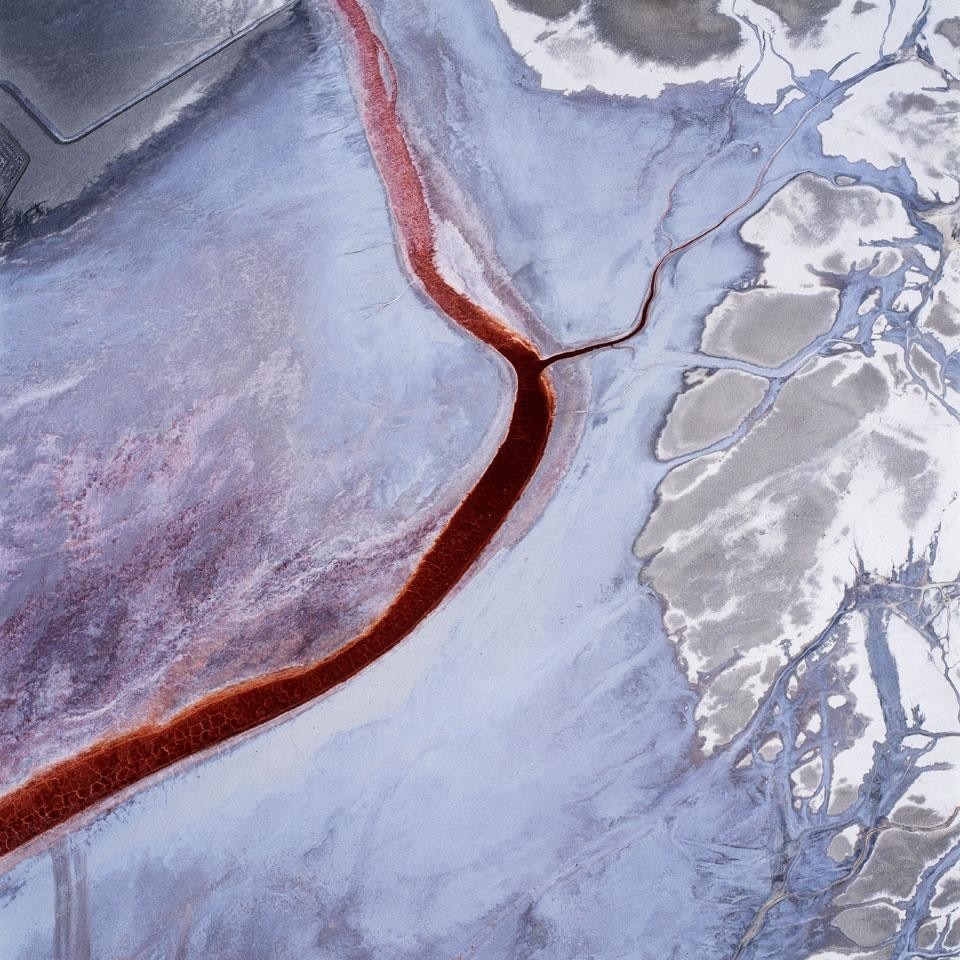

The images on display, mostly of mines and lakes embedded in the Western American landscape and photographed from an aerial perspective, were all obtained from a distance that has been increasing over the years since Maisel started working on this project in the '80s. The prospect the viewer is asked to share, and the proper standard by which to measure Maisel's vision, in other words, is no longer the all-too-human bird's-eye view, but the god's-eye view of Wallace Stevens' necessary angel, who has inspired Maisel's work from its inception, as we learn from the magnificent volume that has been released in conjunction with the exhibition. The paradoxical title of both exhibition and book is borrowed, on the other hand, from another American poet, Mark Strand, while the category "apocalyptic sublime" is used to refer to Maisel's images in their subtitle and in a number of the informative and insightful essays in the book. And yet there is an almost classical serenity to the images that belies the label.

In Maisel's sight we are privileged to experience the exhilarating flight of an imagination that keeps hovering in perfect balance between the earth and the sun

Maisel's maps are at first sight claustrophobic, leaving apparently no breathing space, and yet there is a way out of the labyrinth in the vertical rhythm of the images: there is certainty to be found in their orientation, they are irreversible. They are as they ought to be "in their slow ascent/into themselves," to quote Strand's poem, and "as they rise into being/they are like breath," and one catches one's own breath, as well. By a happy coincidence, the exhibition happens on the same campus on which the great experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage taught for many years until his untimely death in 2003, whose tenth anniversary was just celebrated.

David Maisel/Black Maps: American Landscape and the Apocalyptic Sublime

CU Art Museum

318 UCB, VAC, 1085 18th Street, Boulder, Colorado