All this to say that I certainly hope we're past the point of having to defend film as an art form — though what better way to beat that dead horse than by looking back at the remarkable works of Kubrick? However, we may not be past the point of discovering new ways to present that art form within the static confines of white walls. Short of screening Kubrick's opuses in full, how can an exhibition do justice to the atmospheres, techniques and perhaps even neuroses created by a director, without deviating from the works in question, oversimplifying them or, God forbid, hyper-intellectualising?

The matter of fact tone and direct nature of such captions throughout the show do well to allow Kubrick's work to do most of the talking, and refrain from clashing with the artistic flourishes of the director or the personal reactions of the viewer

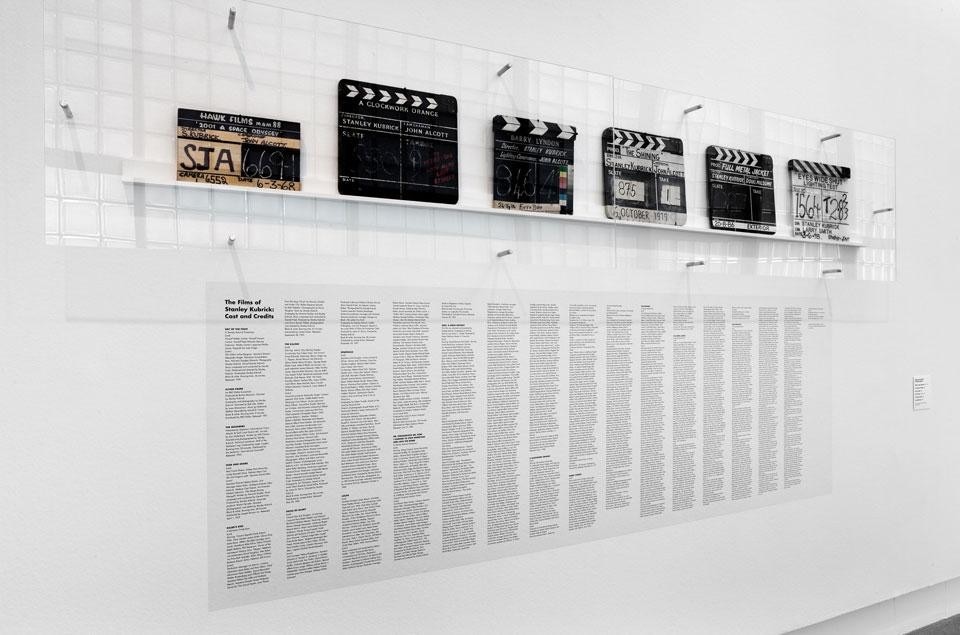

Stanley Kubrick

LACMA

5905 Wilshire Blvd, Los Angeles