"The more impalpable and invisible, user-friendly and communicative the machines around us become, the more pressing is the need to reinvestigate the prehistory of our digital era. Examining how the image of the machine evolved in the twentieth century—especially after the fifties, when the mechanical paradigm began to be replaced by a digital one— is ever more critical. Amid the clanking of rusty engines, the twists and turns of pumps and pipes, or the first fantasies of integrated circuits, computers, and post-human machinery, might we find a key to unlocking the myths behind our smartphones and our society of images?"

These words by Massimiliano Gioni form the premise of Ghosts in the Machine, a recent exhibition at the New Museum, curated by Gioni with Gary Carrion-Murayari.

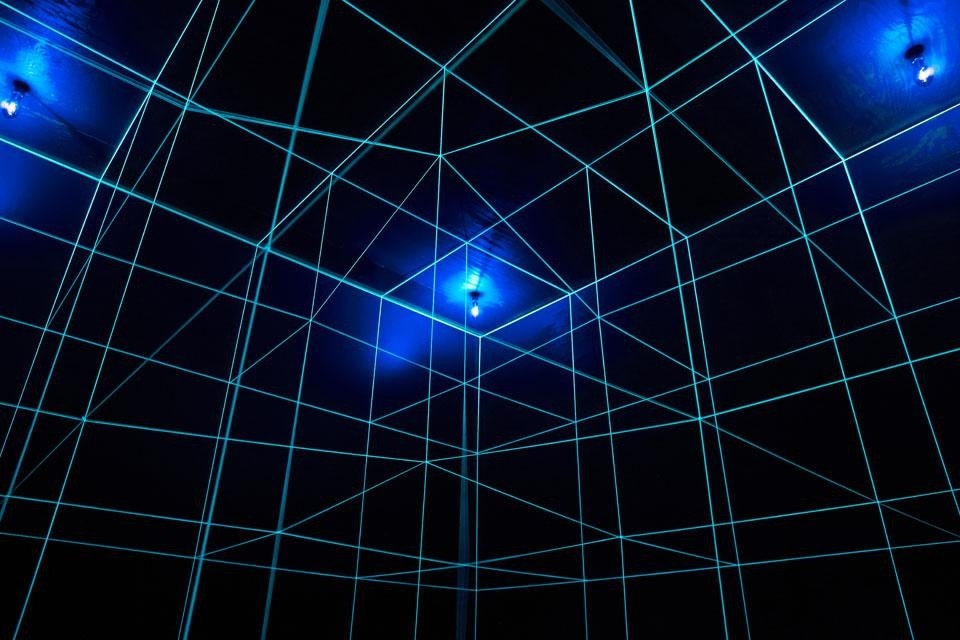

This measured and coherent exhibition, as clear as a mathematical equation, does have its moments of spectacle, such as the reproduction of the machine that executes the condemned man by inscribing his crimes on his body, conjured up by Frank Kafka in his In the Penal Colony, and Stan VanDerBeek's Movie-Drome temple of the moving picture, a hemispherical room in which to immerse yourself in a never-ending repertoire of all that is human knowledge — the "Google images" of the 1960s. Another prophecy on the digital world comes from Richard Hamilton's Man, Machine and Motion: a maze of images in which visitors are invited to immerse themselves and lose their awareness.

The exhibition is also a machine built by accumulation. A rich anthology of texts — presented as scans from the original editions — in the catalogue provides the theoretical means to find the reasons and consequences of a new, potential relationship with technology