Complementing the Villa Noailles records and on display are craft artefacts, photographs, writings and magazines from the Musée de l'Homme and Quai Branly, alongside material from university collections, archives, libraries and private collections. Together, they paint a mosaic picture of the intellectual relationships developed by Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles, which gave rise to an African expedition in the melting pot of the age d'or that radically changed the concept of the ethnographic museum. Between Dogon masks and zoomorphic figures from Benin, sculpted heads from Mali, seats and musical instruments of native African peoples from the early 20th century, the story of the museum and the multifaceted Noailles patronage is narrated.

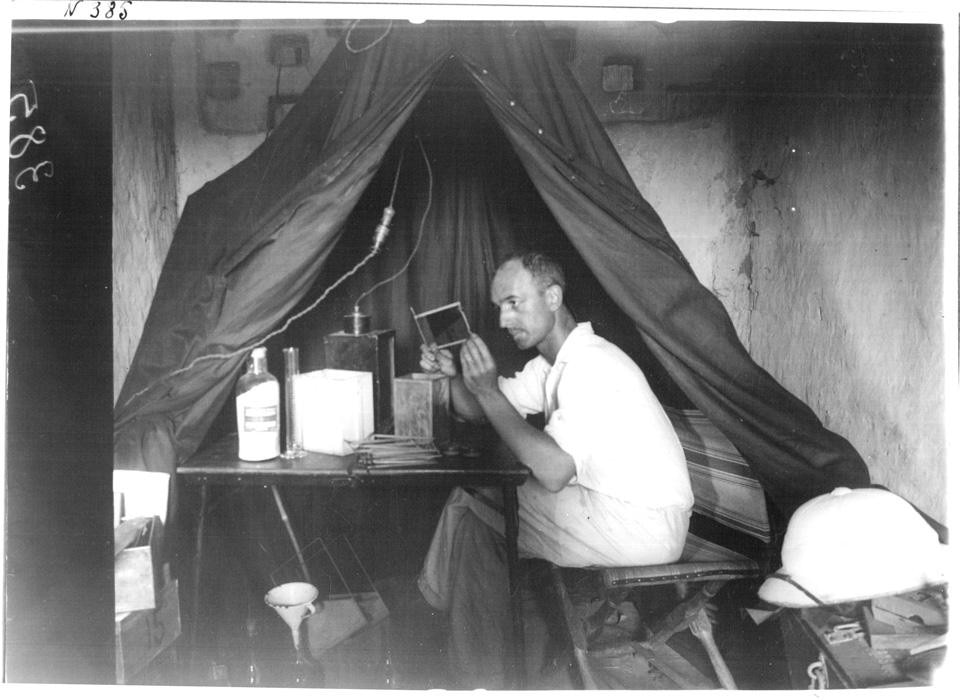

The exhibition begins with the words of Marie-Laure: "The city of Amsterdam craves urbanism with identical houses stretching for kilometres around Baudelaire's old canal city. Here, we met Georges-Henri Rivière and I am most enthusiastic about his architecture and the northern European spirit. He was a guest of Baron Van der Heyd, the collector of Negro objects [...] a sort of return to nature and humanity for which we feel a need and that you seem to resolve magnificently with your expedition." It was 6 September 1932 and the construction of the Hyères villa had just been completed when Marie-Laure sent this letter to writer Michel Leiris, who was, at the time, on a yearlong mission between the Atlantic Ocean and the Red Sea. Along with artist Gaston-Louix Roux, musicologist André Schaeffner, linguists Jean Mouchet and Deborah Lifchitz, geographer Abel Faivre, ethnologist Jean Moufle and technical operator Eric Lutten, Leiris covered 800 kilometres with the purpose of documenting the cultures of the peoples in Senegal and Eritrea. This expedition became known as the Mission Dakar-Djibouti and was led by young explorer Marcel Griaule. Although the political context was still dominated by colonial interests when the mission departed, its travel accounts were critical of colonialism's devastating effects and focused, for the first time, on the need to safeguard a vast and as yet still unexplored cultural heritage that was at risk of being eliminated by Western expansionist aims.

It is no coincidence that Leiris, Roux and Schaeffner contributed to the Noailles-backed periodical Documents, or that the Surrealist magazine Minotaure served as a catalogue for the opening exhibition at the Musée Ethnographie du Trocadéro (MET) — the present-day Musée de l'Homme — where the mission artefacts and studies were concentrated. 3,600 objects, 300 manuscripts, 6,000 photographs and 200 sound recordings revolutionised not only the way people looked at overseas countries, but also the very concept of the ethnographic museum. This was not, as so often occurs, an expedition commissioned by a collector who would bequeath his collection to a museum nor, as occurred with the previous colonial expeditions that lay the bases for the MET, an eclectic ensemble arranged like bric-à-brac, as if in a "flea market", as Picasso commented when he visited the old arrangement in 1907, fascinated by the sculpted African masks. The importance and significance of the Mission Dakar-Dijbouti lay in the fact that it broke away from the folklore approach in favour of a culture of the arts and folk traditions that had to be implemented, on the one hand, in the field with fresh approaches to learning about communities and their ways of living and, on the other, in the museum with an exhibition design conceived as an intermediary and pedagogical interface between scientific studies and the public's different knowledge levels. The main person pulling the strings of this modernisation, which became the cornerstone of anthropological museum disciplines, was George-Henri Rivière. Charles de Noailles appreciated the way Rivière has organised an exhibition on pre-Colombian arts at the Pavillon de Marsan, and was also behind an encounter between Paul Rivet, then director of the MET, and Rivière, then a critic for the Cahiers d'Art magazine and one-time manager of Josephine Baker — who opened the music events at the inauguration of the Dakar-Djibouti exhibition in 1933.

Along with artist Gaston-Louix Roux, musicologist André Schaeffner, linguists Jean Mouchet and Deborah Lifchitz, geographer Abel Faivre, ethnologist Jean Moufle and technical operator Eric Lutten, Leiris covered 800 kilometres with the purpose of documenting the cultures of the peoples in Senegal and Eritrea

Mission Dakar-Djibouti: The Story of a House and a Museum. Ethnography Patrons Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles

Villa Noailles

Hyères, France