The Clock is a twenty-four hour cinematic montage that keeps real time by splicing together thousands of film scenes — each one including a wristwatch, a wall clock, a clock tower, or some other cinematic representation of time.

Created by artist Christian Marclay, The Clock debuted in 2010 in London, and made its New York premiere the following year at the Paula Cooper Gallery. After a world tour, it's back in Manhattan, on public view in the David Rubenstein Atrium at Lincoln Center. As I walked into the enormous black box viewing room that fills the entire 650-square-metre atrium space I expected to stay for only a few minutes. After all, how intriguing could 24 hours of film clips be? As it turns out, very intriguing. In the skillful hands of Marclay these fragments of cinema become unexpectedly captivating — perhaps even enlightening. Much to my surprise, I stayed longer than a few minutes. Quite a bit longer, in fact.

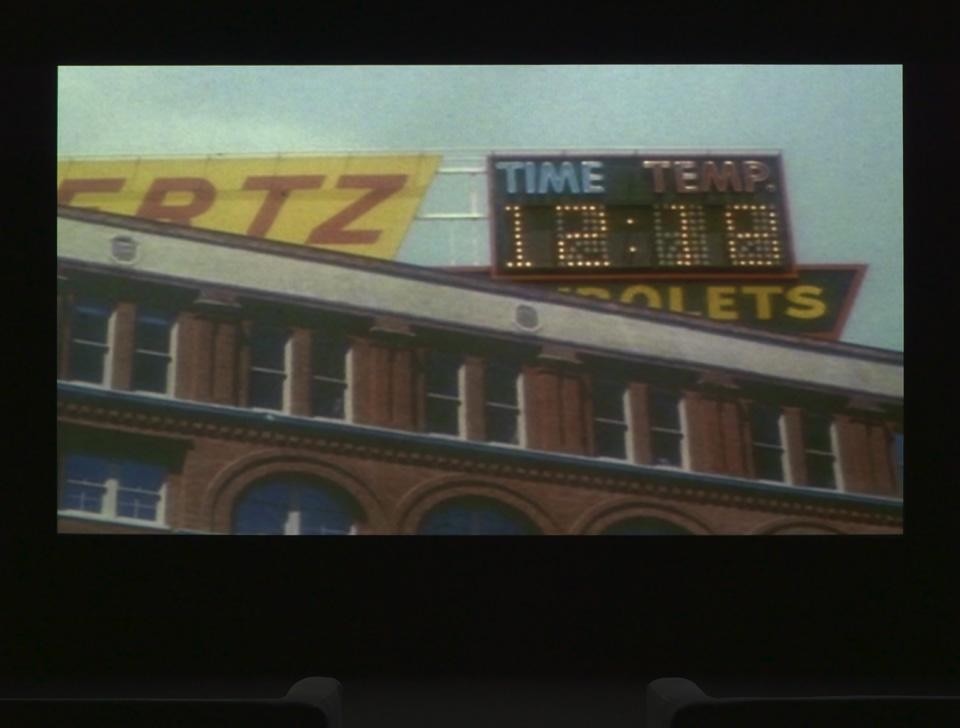

In The Clock, a film clip may show for a few minutes or a few seconds before cutting to another scene from another movie then returning to the previous scene — the time on the clock changing, of course — and then continuing. Cut after cut. Tick after tick. Each scene advancing the hands on a clock another minute, but also advancing a sort of imaginary plot. In the era of the youtube "supercut" — obsessively assembled video montages depicting multiple instances of a cinematic trope or techniques — Marclay's videos stand out with their artful editing that can, at times, imply larger narratives. The music or dialogue for one clip carries over to the next, artfully weaving the many worlds together. A screwball comedy becomes a drama becomes a heist film, and suddenly a man is hanging from a clock tower. Characters from different worlds call and respond to one another, conversing across time and space. Charlie Chaplin one moment, Tom Cruise the next. Here is a nonlinear history of cinema. But, of course, it's also a clock. As mundane and obvious as that may sound, the installation creates a surprisingly unfamiliar experience of time.

Of course, it cannot be easy finding and assembling thousands of images of clocks from so many films. There are bound to be recurring motifs of tropes. During my viewing, Big Ben seemed to be the star of the film — the hands of its great clock timing heists or triggering bombs. But there was another recurrent local: the train station. Train station after train station after train station. The Clock made me fully appreciate just how linked transportation and time are. After all, it was the emergence of trains in the nineteenth century that precipitated the standardization of time. Railroad time is time. Technological innovation has shaped our perception of the world. But the installation makes something else explicit — the nature of film itself.

Today we measure out our lives in coffee spoons or billable hours and, through portable digital technologies, have the capability to escape the banality of the present moment — a role more traditionally reserved for cinema. The Clock undoes the notion of cinema as escapism, instead serving as a constant reminder of the present moment — of schedules, dates and responsibilities. It is very strange feeling indeed to constantly have an awareness of the exact time while watching a film. At once familiar and unfamiliar, the installation is a sort of anti-movie. Despite this, it entertains. More than that, it enthralls. A few more minutes, I kept telling myself, just a few more minutes. With looming deadlines and an imminent meeting across town, I literally watched every spare minute I had tick by on screen. And yet I felt compelled to stay.

The Clock was selected by the Lincoln Center Art Committee to inaugurate its post-redevelopment public art initiative. One would be hard pressed to find a more appropriate piece. After all, Lincoln Center is itself a timeless montage of great art that, with its recent renovations, is still firmly rooted in the present moment

Christian Marclay: The Clock

David Rubenstein Atrium, Lincoln Center

Broadway between 62nd and 63rd Streets, New York

Tuesday to Thursday, 8:00 to 22:00. Running continuously from Friday at 8:00 through Sunday at 22:00. Closed on Monday.