Manifesta is an itinerant biennial founded in the early nineties as a platform for investigating political, social and economic change underway — through an European lens. Among its guiding principles is its location: it is held in marginal areas that are not yet central to artistic production. This edition takes place at the gates of Genk, a small town halfway between Brussels, Eindhoven and Maastricht, in the Limburg region of Belgium. Inhabited mainly by miners, and developed primarily in relation to the presence of coal mines, this area has long been considered a sort of industrial hinterland in Europe. Today, a large percentage of Genk's population is made up of children and grandchildren of miners, who were originally late 19th century migrants, mostly from Italy. It is worth remembering that until not so long ago, Italy was a country of emigration; only in 1974 did the trend reverse.

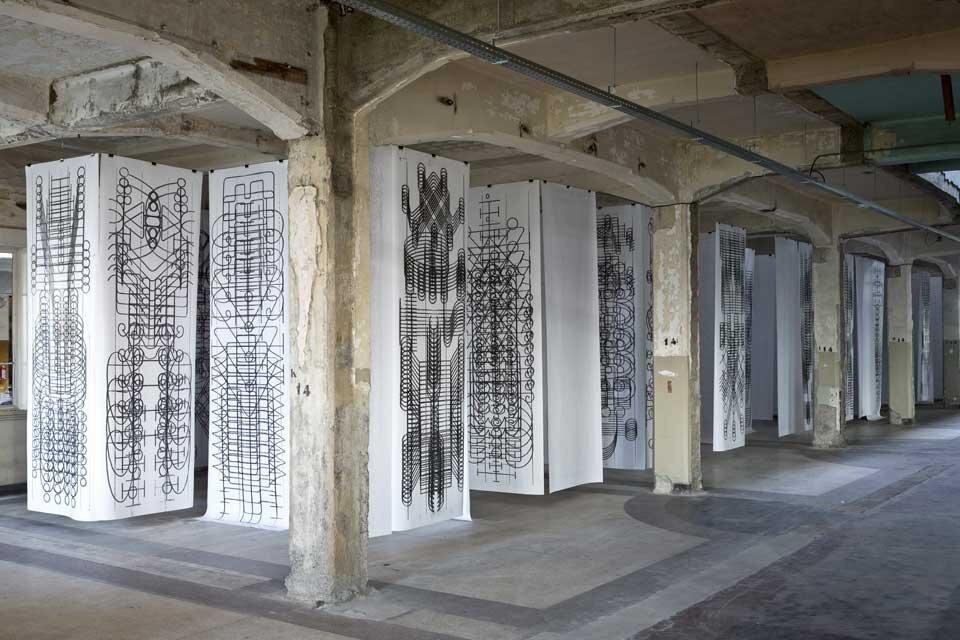

The Deep of the Modern is concentrated in one location, an empty and dilapidated building at the Waterschei mining site. The show occupies three floors, with sections defined according to the building's structure. The exhibition space on the ground floor houses objects and documents; it is a web of history, stories and memories relating to the mining activity of the recent past. The first floor houses works by major artists from the post-war era, from Duchamp to Beuys, Broodthaers to Richard Long; part of the space, insulated and air conditioned, includes works from the history of art between the 19th and 20th centuries. The third floor hosts thirty-five contemporary artists, many of whom were invited to create new projects addressing the issue of labour, in light of our current zeitgeist. In fact, the show's true theme is our everchanging economic system, continuously transforming the terms and conditions of labour and social relations.

The exhibition unfolds in a continuous back-and-forth, freeing itself from the tendency to see context-specific work as a way to claim a local identity to be preserved and defended

In this "historical" section, the pieces on display find their lowest common denominator in the mining landscape and the work and life of miners. The works range from the sublime to the picturesque, interpreting industrial sites as dramatic and grandiose elements; representing scenes of an underground hell and considering the aesthetics of pollution; going from a realism that sees workers as the main characters on the scene to Stakhanovism. Work and workers are the central elements of representation.

Manifesta 9's The Deep of the Modern unfolds in a continuous back-and-forth between questions and answers, freeing itself from the tendency to see context-specific work as a way to claim a local identity to be preserved and defended. The show's site and venue create, instead, a paradigmatic situation, which allows reflection upon the transformation of cultural, industrial, economic and relational models that go well beyond a specific context. Beyond an interesting exhibition, The Deep of the Modern is an important curatorial essay. Gabi Scardi