The sociologist Paul Gilroy, in his long essay entitled The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness has provided us with one of the most comprehensive texts on the subject. Gilroy outlines a critical analysis of the topic of race with the aim of tracing the history of transatlantic black culture as viewed through literary, poetic, artistic and musical production. The author is careful to emphasize its syncretic aspect and at the same time vigorously distances himself from both primitivism and from weak exotic models. In the arts, one of the most enlightening exhibitions on the subject was produced last year at Tate Liverpool; stemming from Gilroy's book, the show, Afro Modern: Journey through the Black Atlantic, which is based on current ethnographic research, focused on 140 works divided into thematic sections highlighting the impact and influence of different black cultures—African, Caribbean and South American—on Western art and vice versa.

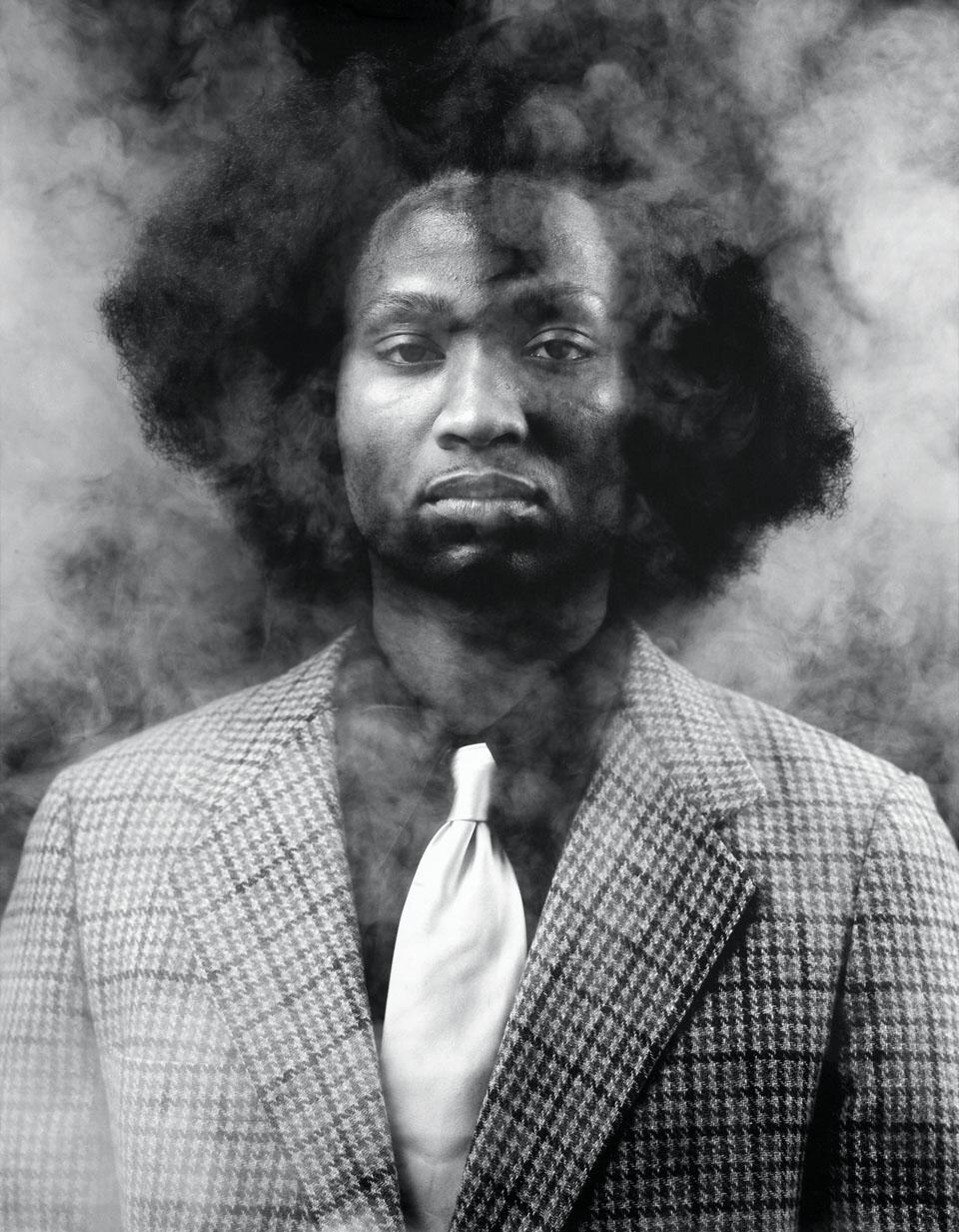

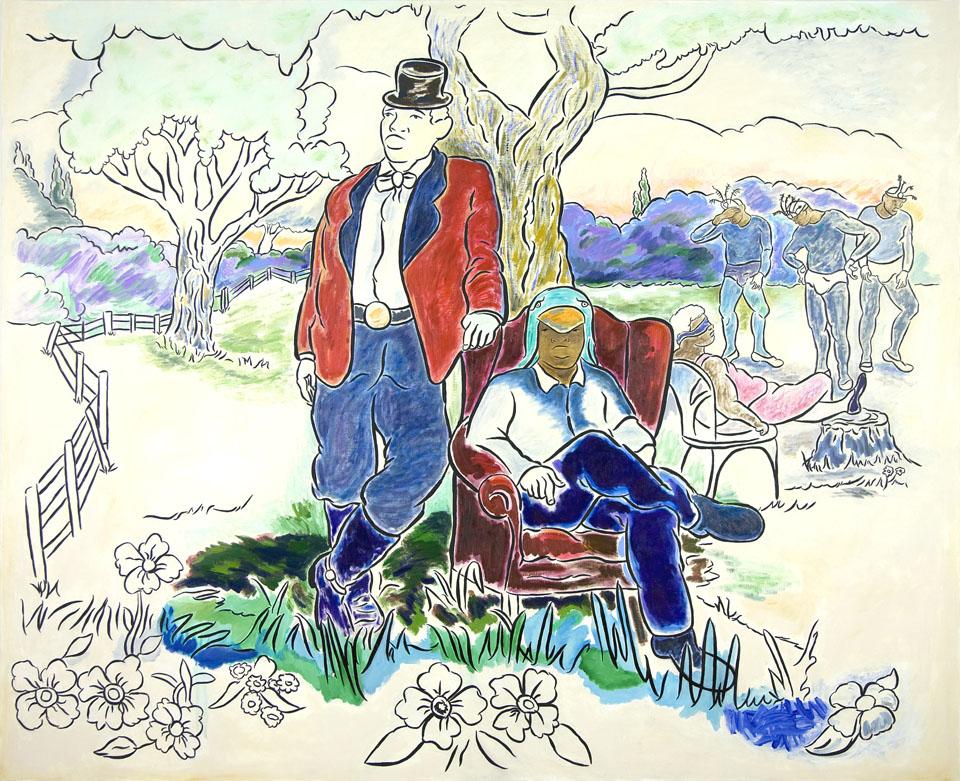

Group portrait above, L to R: Rashid Johnson, Nick Cave, Kalup Linzy, Jeff Sonhouse, Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems, Barkley L. Hendricks, Hank Willis Thomas (blue shirt in the front), Xaviera Simmons, Purvis Young, John Bankston, Nina Chanel Abney, Henry Taylor, Mickalene Thomas (sitting in front), Kerry James Marshall, and Shinique Smith. Photo Credit: Kwaku Alston

The Rubell is located near the Puerto Rican neighborhood of Little San Juan, also known as El Barrio, which began illegally and where people do not take often kindly to all these glamorous changes that have led to an increase in prices of essential goods.

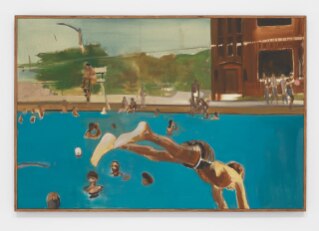

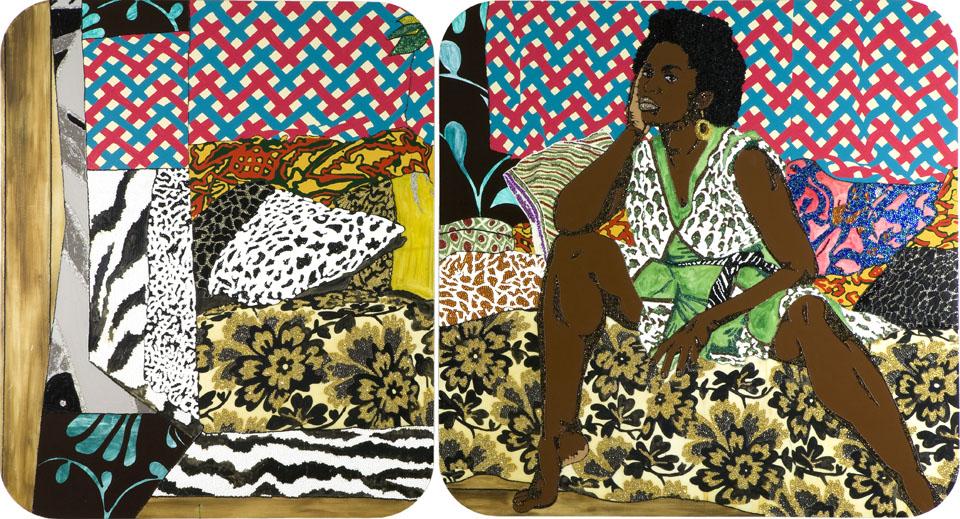

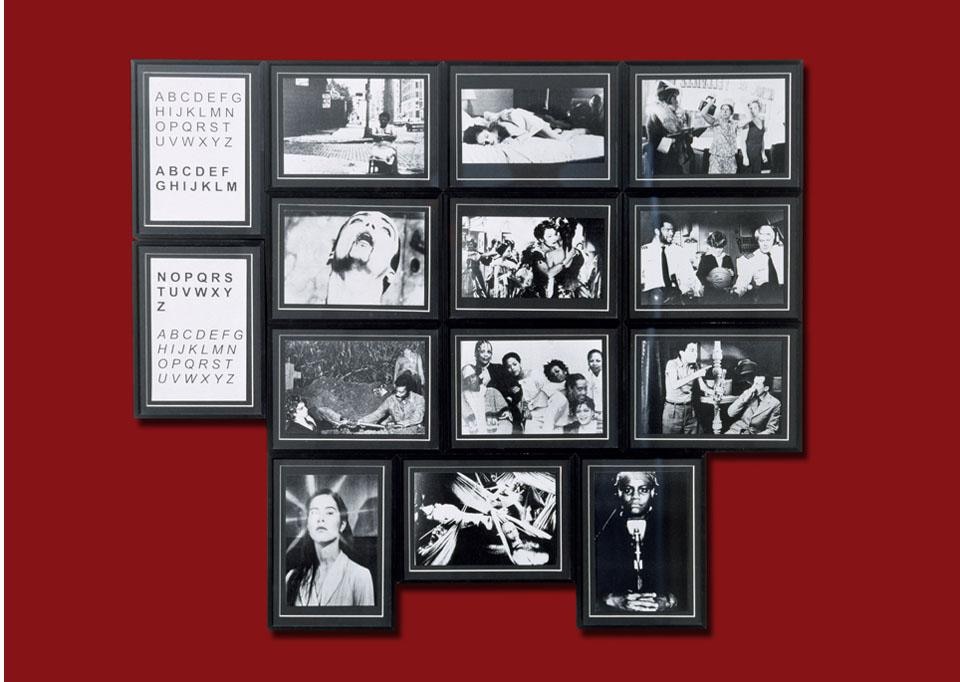

If the predominant medium is the traditional canvas, quite widespread since it is a private collection, the most striking aspect of the exhibit content is the absolutely shared conceptual basis of the pieces. It is clear that the artistic research always points to the politics of identity just as most of the pieces do not conceal the conflict with the theme of double consciousness.

![Iona Rozeal Brown, <i>Untitled (after Kikugawa Eizan's "Furyu nana komachi" [The Modern Seven Komashi]),</i> 2007. Acrylic and paper on wooden panel, 12 x 14 5/8 in. Rubell Family Collection, Miami Iona Rozeal Brown, <i>Untitled (after Kikugawa Eizan's "Furyu nana komachi" [The Modern Seven Komashi]),</i> 2007. Acrylic and paper on wooden panel, 12 x 14 5/8 in. Rubell Family Collection, Miami](/content/dam/domusweb/en/art/2011/04/23/30-americans/big_340202_1425_Brown-IR_Untitled_afterKikugawa1.jpg.foto.rmedium.jpg)

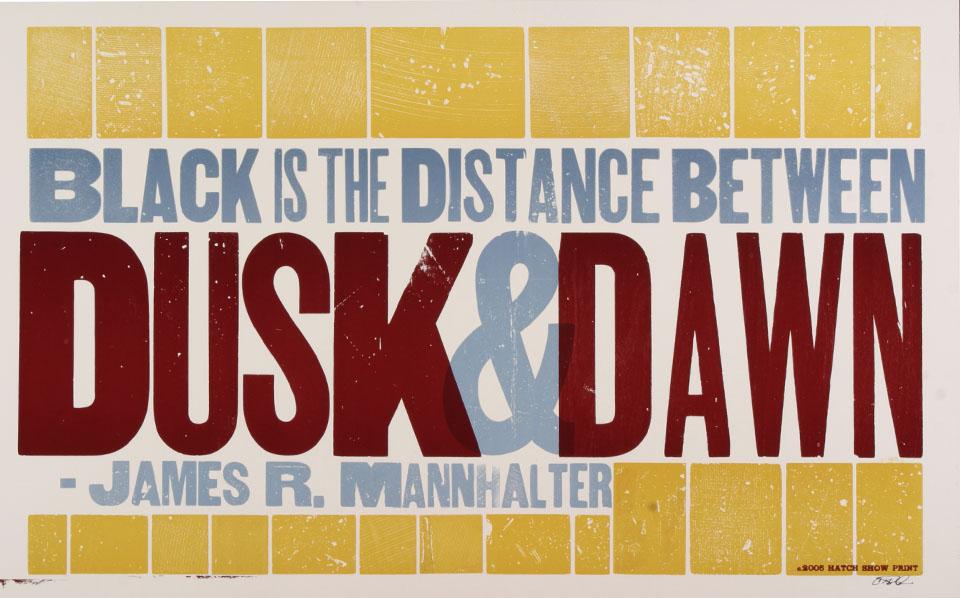

In a conversation a few years ago, the artist Kori Newkirk, one of the most incisive authors on the topic of identity, proposed a series of successful sculptural installations hastily named "Curteins" which represented bare landscapes using beads—the plastic beads with which Africans decorate their hair. I asked him if this fashion was still very popular in the U.S. The answer was that in fact it was no longer so popular but that it was intimately tied to a typically African image and ecology of belonging. In the project at Celebration of Blackness, promoted by the Mobile Museum of Art, Carl Pope, a true outsider who chose not to tie himself to any private gallery and who only works with public spaces to avoid any possible mediation with the market in order not to limit his freedom of expression, wrote on several large billboards penetrating and simple phrases like, "Black is the distance between dusk and dawn," or "The Absence of color is still a color."