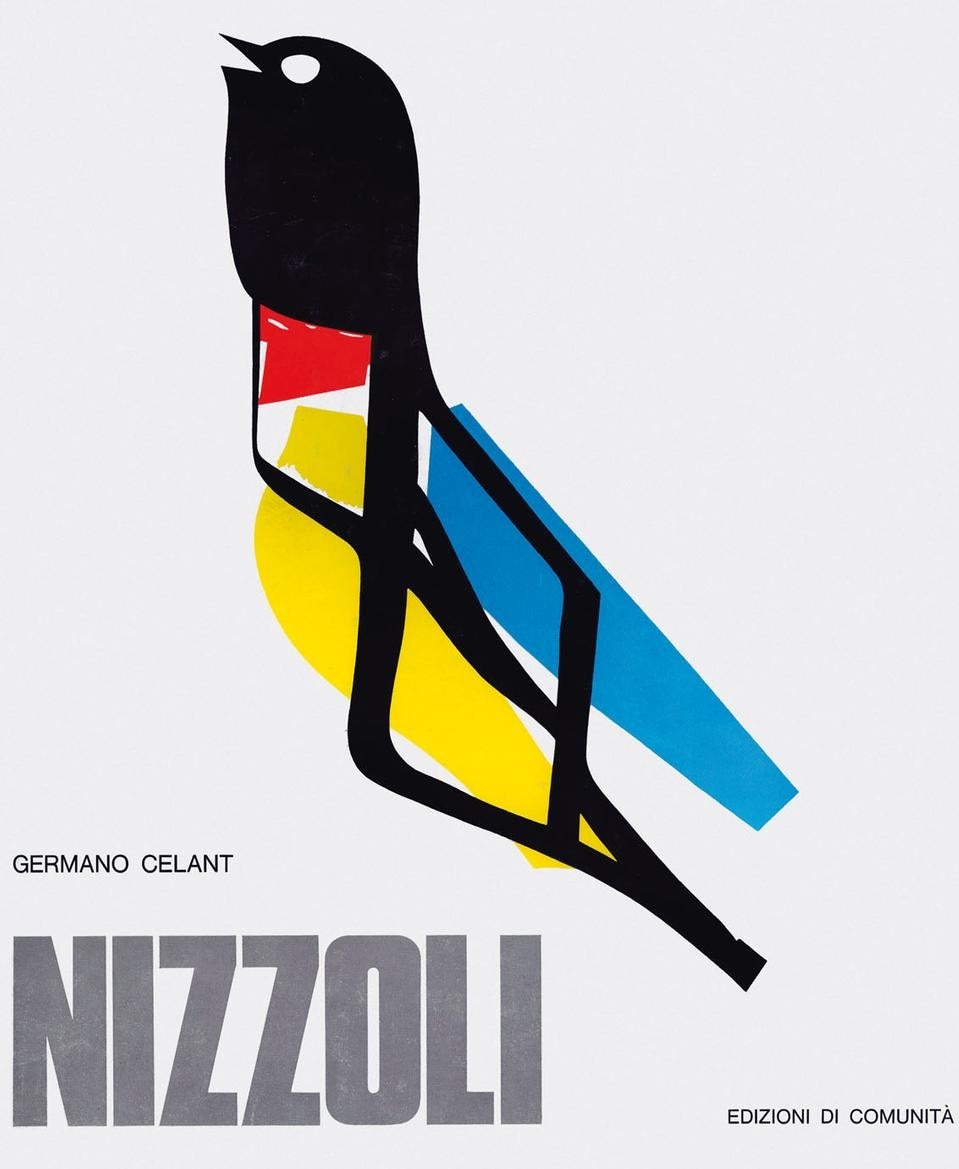

Germano Celant : My work is marked by a historical frame of reference. It is an approach that I learned at university from Eugenio Battisti. He believed that analytical consideration could be practiced on any artistic subject whatsoever – from watches to witches, from robots to Brunelleschi. Since then, I have studied my subjects from a 360-degree angle, whether art, design, architecture or any combination thereof. My nonpreferential attitude began when I worked for a few years as the editorial secretary of Marcatrè magazine (founded in 1963, first based in Genoa, then Milan). Marcatrè united the different realms of architecture, art, design, music and literature. Editors-in-chief were Paolo Portoghesi, Eugenio Battisti, Diego Carpitella, Maurizio Calvesi, Umberto Eco, Vittorio Gelmetti and Edoardo Sanguineti. That was when my interest in the cross-pollination between the arts began. Then I wrote the first monograph on Nizzoli, who started out as an artist and then became an architect-designer, corresponding perfectly with my interest in creativity that touches on different aspects of reality. Writing about Nizzoli brought me into contact with his office Nizzoli Associati. There I met Alessandro Mendini, who invited me to collaborate with Casabella, of which he was editor at the time. Working in the context of an architectural magazine stimulated me to find an osmosis between art and architecture. From then on, my interests blended. As a historian and theoretician I have been focused on the fusion and confusion of the arts since 1969: from Radical Architecture to Arte Povera, from thematic analysis (found in the exhibitions "Arte & Ambiente" at the Venice Biennale, 1976; "Arte & Moda" in Florence, 1996; "Arte & Architettura" in Genoa, 2004) to a historical, wide-ranging and non-sectarian reading of the arts (such as in the exhibitions "Identité Italienne" at the Centre Pompidou, 1981; "European Iceberg" at the Art Gallery of Ontario, 1984; "Italian Metamorphosis" at the Guggenheim Museum, 1994; "Vertigo, Arte & Media" at the MAMbo in Bologna, 2007).

D:After the "warm" phase of Arte Povera, your work necessarily became more complex, diversified and "cold". What models of art criticism have you applied over the years to the changing socio-political conditions in art and society?

GC: My training as an art historian is inevitably reflected in my way of working, meaning that I treat each research subject with rigorous methodology and specific attention to historical context. I do this to distance myself from the creative and journalistic kind of art criticism that does not lead to a scientific and analytical contribution. At most it leads to a self-referential exercise dressed up in poetic writing that conceals a lack of analysis and interpretation. I am stimulated by work done here in Italy, and have found similar wavelengths in a group of artists that includes Mario Merz, Jannis Kounellis, Luciano Fabro, Giulio Paolini, Giovanni Anselmo, Alighiero Boetti, Giuseppe Penone and Gilberto Zorio. They work in an artistic dimension that is fluid and mobile, not rigid and static as in traditional painting and sculpture. The unpredictable and unstable advancing of Arte Povera, as well as land art, conceptual art or body art (all the subject of events and exhibitions that I organise) makes me understand how site-specific or context-specific work has its own logic when it comes to art criticism and "linguistics". Daniel Buren, Maria Nordman, Michael Asher and Hans Haacke have made this clear. This is where my contribution to the "language" of an exhibition or exposition originates: not a flat display of objects, but a picture book that tells a story in a certain place and time. In the early '70s, by putting into practice what I had learned while studying Nizzoli and working at Casabella, I observed how art critics and art historians were unable to interpret or linguistically manage the physical surroundings and the method of exhibitions. They proceeded by fragments of attention to single objects. I began collaborating with architects, interior designers and graphic designers in order to exchange ideas and create an in-depth display of art. In 1976, I was invited by Pontus Hulten and Vittorio Gregotti to be a curator at the Venice Biennale. Together with Gino Valle and Pierluigi Cerri, I staged the "Arte & Ambiente" exhibition. From there, I began my exhibition career, collaborating with Gae Aulenti, Jean Nouvel, Achille Castiglioni, Rem Koolhaas, Massimo Vignelli, Frank Gehry, Pierluigi Cerri and Renzo Piano. This was a transition from the "warm" exchange with artists to the "cool" studying of exhibition methods with architects.

The exhibition on the subject of surroundings, from futurism to body art, was connected to the theme of the Biennale – the environment – and I treated the subject matter in a historical way. I started with the Italian and Russian futurists, from Balla to Tatlin, and developed the story with more spectacular examples: El Lissitzky, Mondrian, Kandinsky, Duchamp, Van Doesburg and Schlemmer. Then I covered the '70s with Fontana, Arman, Warhol and Pistoletto. Flanking the historical overview, I invited contemporary artists to make a site-specific piece of work: Nauman, Irwin, Merz, Kounellis, Acconci, Buren, Asher, Wheeler, Nordman, Beuys and Palermo. This way of presenting – to give a strong historical matrix to contemporary work – marked all the following exhibitions that were combinations of art and fashion, architecture, media, etc.

D:You are senior curator at the Solomon Guggenheim Museum, artistic director of the Fondazione Prada, and director of art and architecture at the Milan Triennale. How do you combine these roles? Besides conceiving the contents, what types of venue does an intellectual manager need to design/ activate/use these days?

GC: It was precisely from the way architecture and design offices operate that I learned that work needs to be done in teams and each project needs to be structured and shared in its creative, curatorial and production aspects. The principal establishes the general lines of a project. Then he or she coordinates and controls the work method and its development according to his or her view. The principal lets a group of collaborators carry out the project, systematically verifying progress (and sometimes drastically changing the initial idea) until the final phase where things become concrete. Since 1989, when I became a curator at the Guggenheim in New York and then the artistic director of the Fondazione Prada in 1995, I have applied this pluralist, fusionist approach, where the theme is finalised, along with the historical and artistic line, together with the people from the institutions: Tom Krens in New York, and Miuccia Prada and Patrizio Bertelli in Milan. Then teams of assistant curators and researchers execute the plan. This is how it works at the Milan Triennale, directed by Davide Rampello, and the Fondazione Emilio e Annabianca Vedova, too. For each event (such as Frank Gehry at the Milan Triennale, Gio Ponti at the New York Triennale, and the Louise Bourgeois show at the Fondazione Vedova in Venice) an internal team of researchers is expanded with specialised collaborators for the interior displays, graphic design and communications. This is yet another interweaving of different languages that is not normally practised by academics, theoreticians or art historians. My experience at the Guggenheim Museum under Tom Krens was pivotal, because it showed me a museum's cultural broadening and design-related openness. There is not a museum in the world that succeeds in covering the history of contemporary art from 1968 to today in a dignified fashion. An enlargement of scale and the use of deserts and outdoor landscapes make it necessary for museums to widen their territories. They need to be able to display minimal sculpture, where each piece of work needs its own room, land art, and have a permanent hall for performances. As recently seen with Marina Abramovic, museums can show live re-enactments of performance art and happenings. This makes it clear that new museums need an enormous amount of space. The Guggenheim is travelling this road, widening its territory, by first aggregating Bilbao, then Berlin, and now Abu Dhabi. The latter will cover 50,000 square metres (five times the Bilbao Guggenheim) for global art, including Asia, from the Middle East to China, and the Western world, from Africa to Europe and the Americas. Naturally, there are alternatives to this globalisation and gigantism, and perhaps they will lead to a change in the identity of single museums. This might entail moving away from the all-encompassing art approach to take a specific, unique stance – like the old-fashioned museums of armour, science or transportation – only with subjects that represent a moment in contemporary history, meaning a slice of the last 50 years. To follow a thread and become specialised would mean becoming an "absolute" hub of land art or media art or performance art or conceptual art. Such focus would lead to a uniqueness that would, hopefully, be recognised all over the world. In addition, varying temporary events could maintain the public's interest and attention for that specific institution. This is what the Vedova Foundation is doing: its mission is to kindle interest in the artwork of Emilio Vedova, therefore it organises exhibitions of his contemporaries, from Louise Bourgeois to Luigi Nono.

D: After your felicitous coining of Arte Povera, it has become increasingly difficult to describe artistic movements meaningfully with just one or two words, although you did invent "Inexpressionism". How do you invent these definitions? What definitions would you give to current art movements?

GC: Since the globalisation of art in the '90s, the parameters of interpretation and codification have been annulled, because the coordinates have become too dilated. Direct knowledge of all that is going on has become impossible. One would have to include Europe, the US, China, Latin America, India and Africa. The process of popularisation and "registering" by trends (pop art, minimal art, Arte Povera, transavantgarde, etc.) has given way to national groupings. There have been waves of art that was Russian, Chinese, Indian or African, usually related to those countries' emerging economic power. Once national recognition has been acquired, art is inevitably forced to seek ulterior "evaluation", not only abstract but also concrete and recognisable by all. Museums and art historians have been unseated by auction houses that are implicated in rising market prices, whether those prices are manipulated or not. They began quoting international prices that were gradually accepted on a global scale. The art chain is still made up of artists, gallery owners, art critics and museums, but it has been lengthened to include art fairs and auctions that "announce" the real consecration: money worth. This is the singularity of artists who have turned into stars (Hirst, Koons, Cattelan): they follow the mindset and practice of Andy Warhol, meaning that most of their interest goes out to media coverage and business. It is interesting to note that these same artists are now operating on the other side of the marketplace: they manage their own appearances at auctions, they speculate in real estate like stock brokers, and invest in the art of young artists who represent future developments. This self-management demonstrates extreme financial lucidity. Corresponding to the individualist explosion in art today is an equal idolisation of the collector's personality. It used to be that art collectors (Rockefeller, Guggenheim, Panza di Biumo and Lauder) aspired to placing their acquired pieces in museums. Now, they build their own museum (Eli Broad, Dakis Joannou, Pinault, Arnault, Boros and Rubell) and are their own curators, seeking to exalt their own ideas and preferences, leading to a real estate of art. The consequence is that city museums and national museums will suffer a lessening of their economic and patrimonial power until they can no longer survive without the support of private citizens, who will then turn them into an outlet of self-promotion. Trustees will increasingly oblige these museums to accommodate artists whom they deem important, delegating to directors and curators the management of the building and the presentation of their selection, which is personal and sometimes devoid of any historical interest. This is happening in Italy in a less professional way: politicians command the funds for survival and impose directors and cultural strategies that are highly local, in view of being elected.

D: What is your relationship with magazines, considering you have never wanted to direct one?

GC: I enjoy working with people, not institutions, be they museums or magazines. I like to share my passions and research with others on a personal level. It is difficult for me to think of directing such a complex entity as a museum or magazine, because it calls for a kind of attention that doesn't end with the project at hand, but continues with daily commitment, tight time schedules and planned events. I have preferred to work on projects where I avoid taking on tasks that I'm unfamiliar with and that might disappoint me because they don't correspond to my vision, or better my obsession. By doing this, I have been able to express myself and find my own niche. By branching out from there, I have created my identity, working in osmosis with magazine directors such as Alessandro Mendini and Ingrid Sischy, and museum directors such as Hulten and Krens.

At the same time, intellectual and aesthetic common ground has brought about intense exchanges with artists and architects, with whom I have shared the vital role of laboratory, applying it to my linguistic realm: exhibitions and books that are custom made together with each single artist.

D: How does an "art designer" interact with a space designer in the economic context of a large ephemeral-cultural enterprise (you, Koolhaas and Prada)? And how much has your work been influenced by your relationship with Gehry, whom you helped to discover?

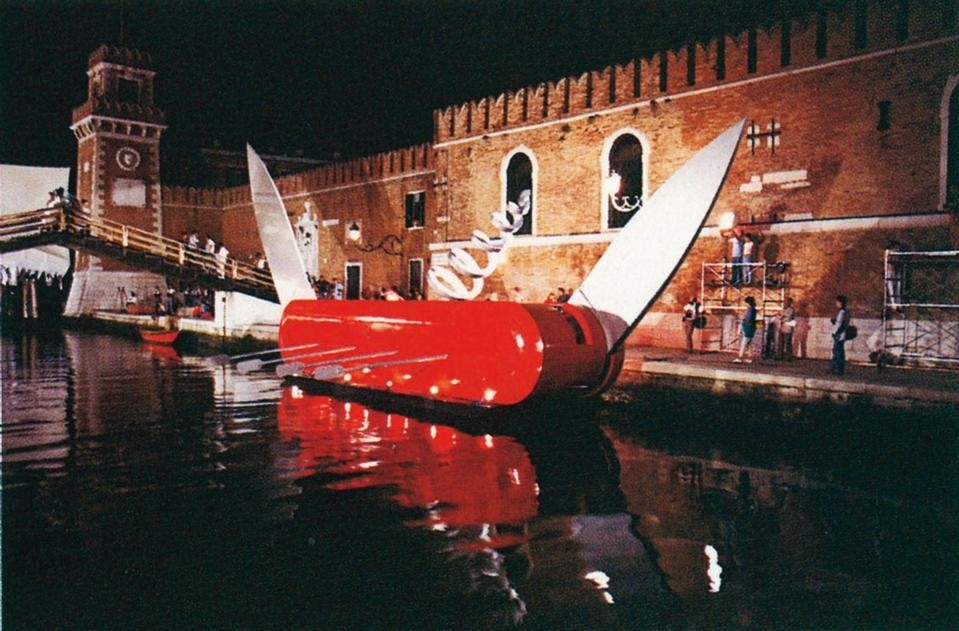

GC: Having begun with Nizzoli and Arte Povera, my perception of aesthetics in architecture, fashion, design and photography is wide open to all kinds of solutions, both functional and not, and all kinds of "linguistic exceptions". That is why my career has been characterised by working with such diverse personalities as Robert Mapplethorpe and Piero Manzoni, Joel-Peter Witkin and John Wesley, Michael Heizer and Miuccia Prada, Joseph Beuys and Frank O. Gehry, Emilio Vedova and Louise Bourgeois, and young artists such as Tobias Rehberger, Nathalie Djurberg, Thomas Demand, Tom Friedman, Francesco Vezzoli, Andreas Slominski and Carsten Höller. I have always worked in an interweaving of visual languages and multiple approaches. So, when I was living in Los Angeles in the '70s, it was natural for me to be interested in Frank Gehry. Then I edited and wrote the introduction for the first Gehry monograph for Rizzoli International. In Italy, I was the curator of his first anthology at the Museo di Rivoli; I helped to organise the performance Corso del Coltello with Claes Oldenburg, Coosje van Bruggen; and in New York, I introduced him to Tom Krens, for whom he designed the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. Frank represents precisely the kind of cross-pollination of form and function, materials and space that belongs to the fluid attitude with which the 21st century began. He has also influenced the road I travel as a historian and theoretician, part of which we have shared in the name of friendship as well as history.

My familiarity with Gehry, his way of working harmoniously with artists (Donald Judd, Richard Serra and Claes Oldenburg) and how he meets museum requirements in his designs (first with Krens for Bilbao, and now for the mega-Guggenheim in Abu Dhabi) helped me become one of Renzo Piano's interlocutors for the Fondazione Emilio e Annabianca Vedova in Venice, and now one of Rem Koolhaas's, who is designing the new Prada Foundation buildings in Milan (in Largo Isarco). This project is full of cooperation, and is based on the fundamental input of Miuccia Prada and Patrizio Bertelli. Decisions are made in consideration of each party's linguistic requirements: the artwork, the collection's logic, expositional methodology, design proposals, size and functions, the conveying of the foundation's image, cost feasibility, innovation in communication and all the other elements that make up an experimental museum building. Here again, teamwork is key, based on mutual openness to suggestions and specific requirements in order to design a dream together.(from a conversation with Stefano Casciani).