Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

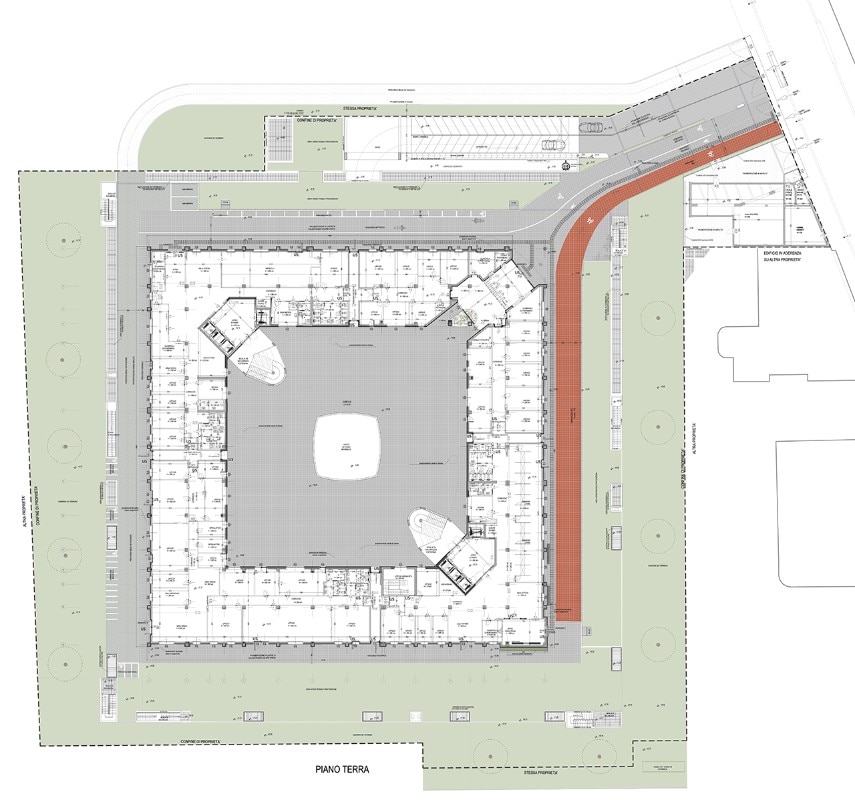

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, site plan

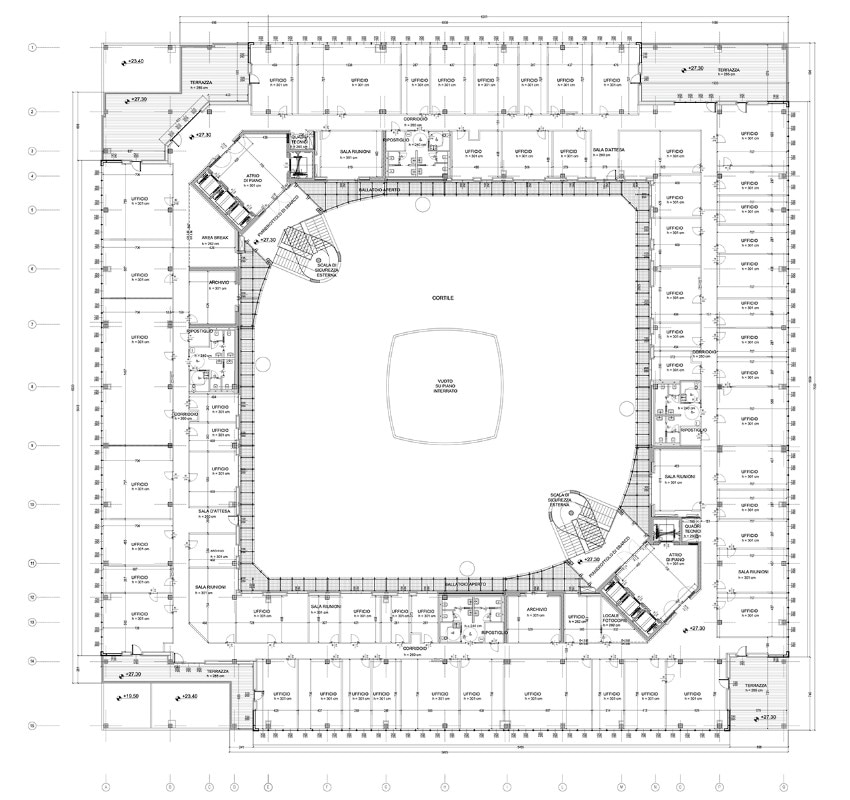

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, 7th floor plan

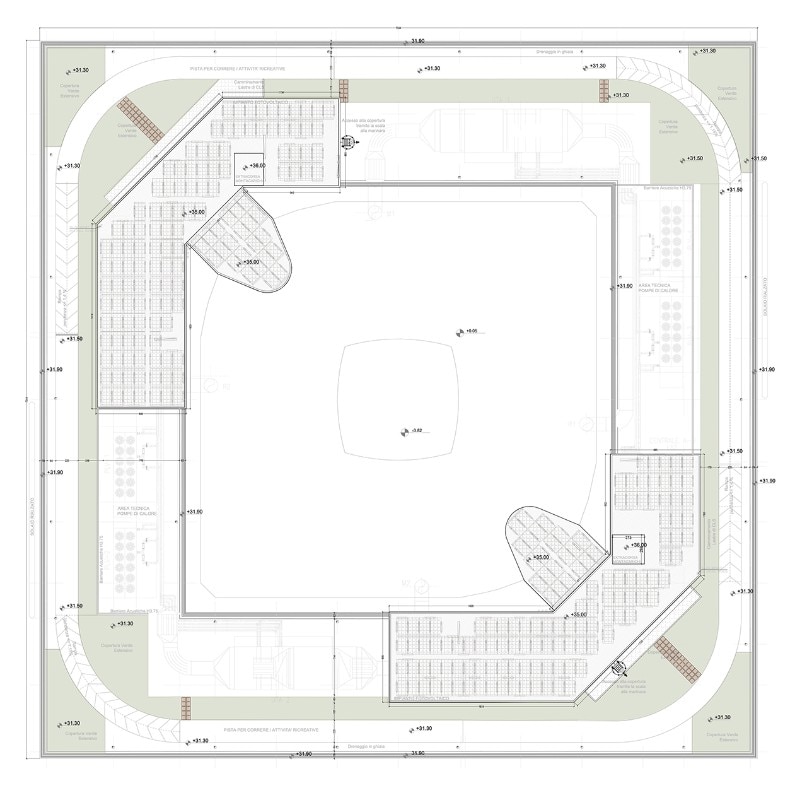

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, roof plan

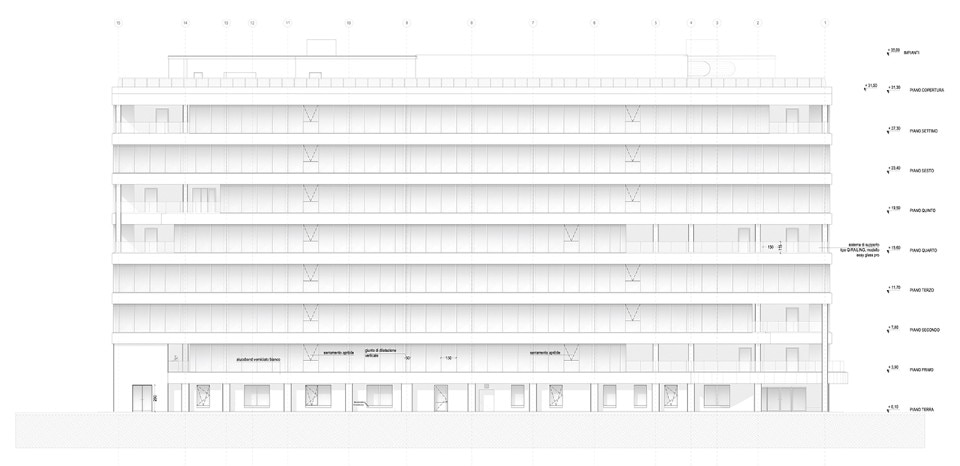

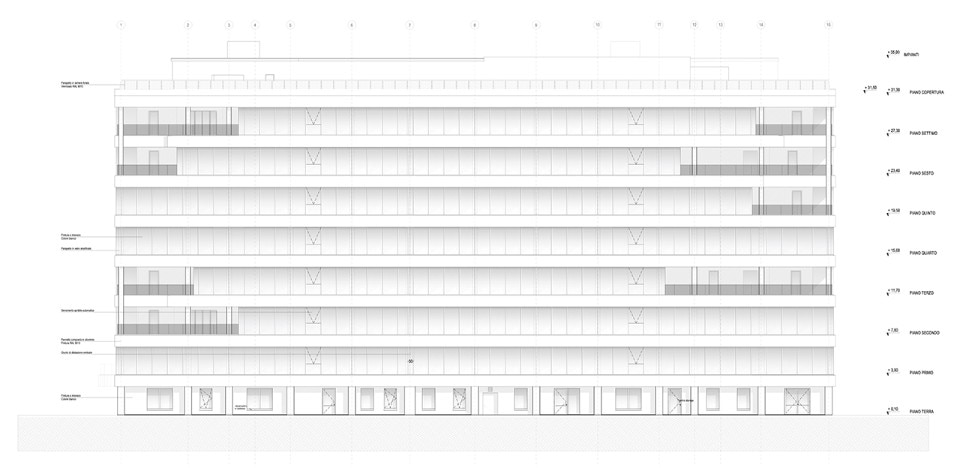

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, north-east elevation

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, south-west elevation

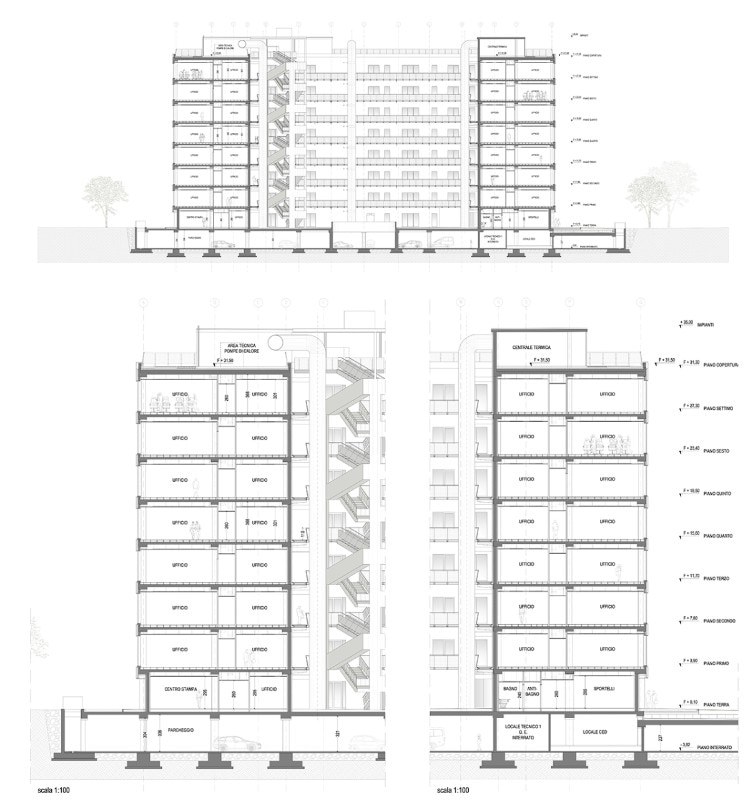

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, sections

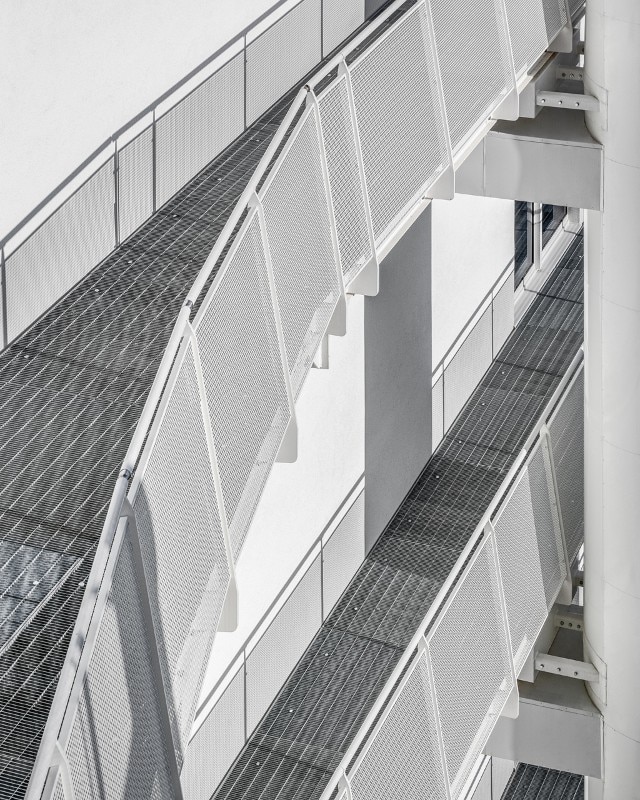

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo

Studio FZ, Municipal office building, via Sile 8, Milano, 2021. Photo © Davide Galli Fotografo