by Ramona Ponzini

Renowned for his unique and surreal vision, Yorgos Lanthimos returns, five years after The Favourite (2018), with a double bill: Poor Things!, the most talked-about and debated film of early 2024, Golden Lion winner at the 80th Venice International Film Festival, winner of two Golden Globes and four Oscars - in both cases Emma Stone was awarded Best Actress -, and Kinds of Kindness, presented at the 77th edition of the Cannes Film Festival, which crowned Jesse Plemons' performance.

His directorial and authorial approach has been instrumental in shaping the Greek Weird Wave, a cinematic movement that emerged in the early 2000s following the legacy of the master Theo Angelopoulos and born out of the socio-economic and political crises in the Hellenic peninsula. This cinematic wave finds its quintessential expression in Lanthimos’ Dogtooth (2009), renowned for its irreverent and groundbreaking experimentation with new linguistic and aesthetic conventions.

The director’s early films delineate a visual landscape characterized by asepticity and symmetry within environments. These films feature minimal set spaces, adorned with simple furnishings and stark interiors of dry design. Over the years, as his productions grow in scale, this spatial aesthetic undergoes a transformation. It moves from urban locations and typically Mediterranean settings to the bleak, dystopian backdrop of Ireland in The Lobster (2015), to the affluent environments of an enigmatic Cincinnati in The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017), to the creaky Jacobean interiors of Hatfield House in The Favourite. Finally, it erupts into a fantastical world, a fusion of organic Art Nouveau and surrealist steampunk, centered on the character of Bella Baxter in Poor Things.

Throughout his filmography, Lanthimos delves into distinct and disconcerting architectural spaces, seamlessly integrating them with the narrative fabric of his films. These worlds act as barriers, their boundaries magnified by the adept use of wide-angle lenses, particularly the extreme fish-eye lens, which compress and confine the actions of the characters.

1. On the beaches of Kineta

Except for the comedy O Kalyteros Mou Filos (2001, My Best Friend), which he co-directed with Lakis Lazopoulos, Kinetta should be regarded as Yorgos Lanthimos’ inaugural feature film. Set in the seaside town of Kineta, on the outskirts of Attica, the macro-environment becomes the backdrop against which the characters maneuver. Here, the director’s focus lies less on their motivations and more on how their obsessions become a manifestation of their personal lives.

The narrative tension is tightly woven into the construction of a fleeting and transient world, with production being its focal point. Is it mere coincidence that the first frame of the movie shows a character pinned to a wall? Kinetta’s story unfolds within the confines of spaces organized in a closed circuit: the hotel with its swimming pool, the recreation area with its tennis courts, and the go-kart track. The color palette exudes a cold, wintry atmosphere. The hotel rooms are depicted as beige and sparse, the bar is decorated with furniture reminiscent of the 1970s, and the exterior is characterized by desolate spaces punctuated by concrete fixtures. The handheld camera, in perpetual motion, leaves the viewer with a lingering sense of exclusion, reinforcing the notion of confinement.

One interesting note: The hotel that served as the focal point of the narrative was the Hanikian Beach Hotel in Agioi Theodoroi, an hour’s drive from Athens. Its recent modernization leaned toward a curvilinear design with rounded white frames, a departure from the stark, angular lines between modernism and brutalism that so effectively complemented Lanthimos’ debut film.

2. Dogtooth’s prison-house

Dogtooth is the story of a character striving to break free from a meticulously constructed and fictional reality. Much like the Baxter household in Poor Things, learning takes place within the confines of the home, albeit through very different methods and with very different results.

The film’s universe revolves around the domestic spaces of a wealthy family’s estate, where the children – a boy and two girls – are isolated and indoctrinated to believe that the outside world is fraught with danger and must be avoided. Their rare opportunity to leave comes unexpectedly when they lose a dog. The father is the only member allowed to venture beyond the confines of the house, commuting to a corporate job, while the mother, also sequestered but complicit, nurtures her children’s upbringing through a lens of enigmatic language and distorted reality.

The catalyst for one of the daughter’s attempts at freedom is the introduction of an anomalous element into the household: a VHS tape, which heralds a new visual narrative and potential means of liberation. In Dogtooth, as in Kinetta, one of the first scenes shows the son’s character pressed against the white wall of the house’s bathroom – a color ubiquitous in conventional European bourgeois interiors, layered with decades of disparate furnishings and acquisitions, with sporadic relics from the 1990s such as outdated televisions and contemporary furniture.

View gallery

View gallery

Fences reappear throughout, as does a predilection for square surfaces, evident in window textures and the tiling of the pool. Exteriors never offer expansive vistas but remain circumscribed, typically by hedges and towering walls. Dogtooth’s totalitarian and dystopian microcosm is materialized through the juxtaposition of interior and exterior spaces, within the anonymity of a house and garden where contemporary man’s loss of identity is consummated.

3. The locations of The Lobster’s sentimental dystopia

The systematization of coercion extends to a broader societal level in the dystopian realm of The Lobster, where singleness is strictly forbidden. Those who defy this mandate are sent to a hotel, where they must find a mate within forty-five days or face the grim fate of transformation into an animal. The film marks Lanthimos’ transition to major international production and distribution, and boasts a cast that includes Rachel Weisz and Colin Farrell.

View gallery

View gallery

In stark contrast to Kinetta’s austere hotel and sparse furnishings, The Lobster’s “correctional hotel” is a cacophony of drapes, carpets, upholstery, and quilts – an abundance that set designer Jaqueline Abrahams skillfully accentuates to reinforce the boundaries of this universe, which found physical manifestation in locations throughout Ireland, from Dublin to County Kerry and County Cork. The interiors are primarily those of the Eccles Hotel in Glengarriff, while the exteriors feature the Parknasilla Resort & Spa in Derryquin. Here, the dichotomy of home and retreat from Dogtooth’s narrative evolves into a juxtaposition of hotel and forest, introducing a new element to Lanthimos’ visual repertoire.

Inhabited by a cadre of dissidents opposed to the dictatorship of couplehood, the forest offers no real refuge as a regime of non-love and solitude prevails. The third setting shifts to the modern urban landscape of Dublin, where a subjugated population navigates among the residences, eateries, and shopping malls reminiscent of the Romerian memory.

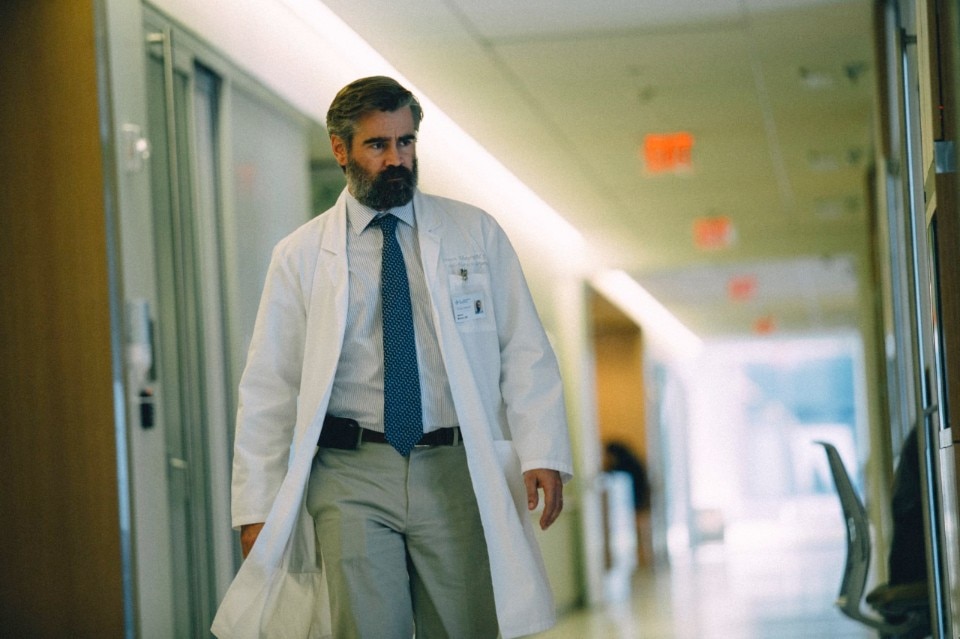

4. The Killing of a Sacred Deer’s Cincinnati

The initial setting of the 2017 film, which marks Lanthimos’s second collaboration with Colin Farrell, cast here as a heart surgeon, is inside the human body – an exposed yet meticulously delineated and confined pulsating organ awaiting surgery. A palpable visceral quality pervades the entire film, which deftly transposes elements of Euripides’ tragedy Iphigenia in Aulis into a contemporary context. As Lanthimos physically distances himself from Greece, he paradoxically draws closer to his cultural roots.

View gallery

View gallery

The hell in which the Murphy family – Steven, Anna, and their children Bob and Kim – find themselves, cursed for sacrificial purposes by the unnervingly sinister Barry Keoghan, unfolds as an inescapable labyrinth. It is articulated through sterile, endless hospital corridors, diners, and the urban sprawl of an unrecognizable Cincinnati, transformed into a realm of opulent single-family homes and 1970s structures that diverge from the sun-drenched allure of California or the sleek modernity of New York.

At one end is the public sphere – a futuristic hospital where Farrell’s character practices medicine and his children are admitted. At the other end is the domestic sphere – the opulent and bourgeois Murphy mansion, decorated with upper-middle-class American sensibilities amidst white wooden furnishings with classical touches. A four-poster bed, stiffened by the director’s frame and stripped of its comfort function, floral curtains, perpetually whirring ceiling fans, a checkered kitchen floor (a motif revisited in The Favourite), and square lattice windows reminiscent of those glimpsed in Dogtooth.

A recurring element that reinforces a delineated geometric boundary is the ceiling paneling in the hospital rooms and restaurants. Further perpetuating the theme of confinement and inevitable destiny, the layering of floor, carpet, and pool table in the basement of the Murphy home acts as a physical barrier, witnessed during a tragic sequence that spirals inward, much like the singular ritual Farrell’s character inadvertently performs to identify the family member destined for sacrifice.

5. The immense Jacobean spaces of The Favourite

The film’s narrative is based on the true story of Abigail Hill, Baroness Masham, who rose to the court of Queen Anne Boleyn of England at the expense of her cousin Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough – ancestor of the famous Winston Churchill – arguably one of the most influential noblewomen in English history. Set against this historical backdrop, the Greek director’s penultimate film boasts an all-star cast, including Emma Stone, Olivia Colman and Rachel Weisz, and was shot primarily in England. Locations such as Hatfield House in Hertfordshire, Hampton Court Palace in Surrey, and Oxford University serve as cinematic backdrops.

View gallery

View gallery

Lanthimos employs quintessential elements of the Jacobean style – the pinnacle of English Renaissance – and reinterprets them through the lens of wide-angle and fish-eye cameras. This stylistic choice is intended to convey the profound isolation of the characters, caught in the trap of blind and ruthless ambition, which brings fleeting triumphs but fails to alleviate the misery of their fate. The interior of the mansion is characterized by intricately carved wood, elaborate furnishings adorned with floral motifs, sumptuous fabrics draping the walls, grandiose fireplaces, four-poster beds, alcoves, and sculptural elements that heighten the sense of opulence.

Scenic designer Fiona Crombie strategically strips the rooms of Hatfield House down to their bare essentials, rearranging furniture to further isolate the characters, while costume designer Sandy Powell opts for black-and-white ensembles for the protagonists, echoing the checkered marble floor on which Horace, the fastest duck in town, navigates through competitors who cement his fame. The lighting choices favor natural or candlelight, recalling the period dramas of another cinematic luminary: Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon.

6. Bella Baxter’s world

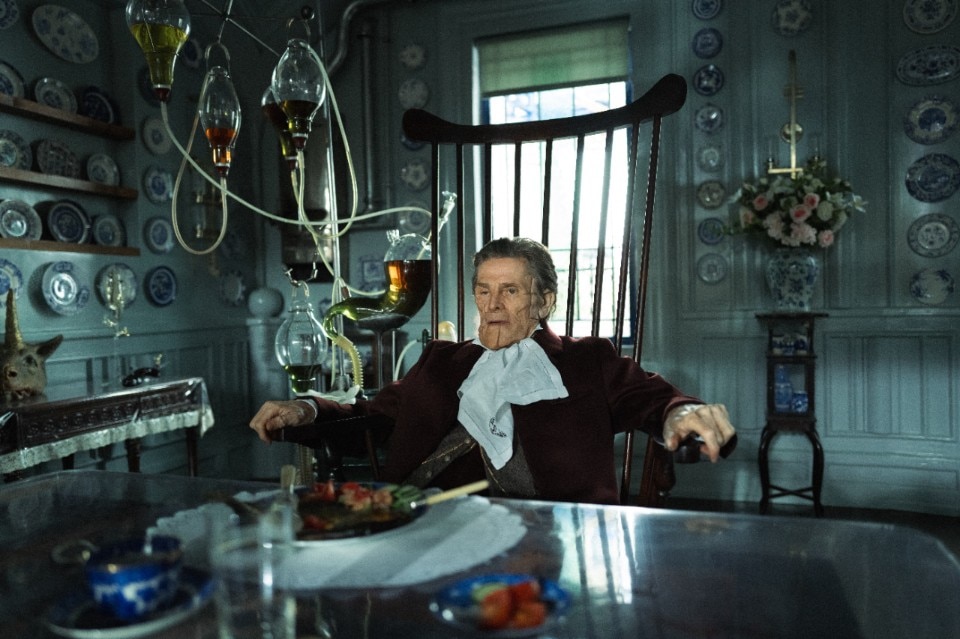

Poor Things unfolds as a narrative centered around Bella Baxter – a universe shaped by, with, and for her. Scientist Godwin “God” Baxter, portrayed by Willem Dafoe, revives Bella, played by Emma Stone, by transplanting the brain of her unborn child, and embarks on a journey of nurturing and guidance as she undergoes remarkable growth before venturing out to explore the world.

Lanthimos, in collaboration with set designers Shona Heath and James Price, crafts unique and extraordinary sets mirroring Bella’s wild imagination as she transitions from infancy to womanhood. The outcome is a fantastical realm reminiscent of Powell and Pressburger films, replete with miniatures, hand-painted backdrops, and rear projections.

View gallery

View gallery

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Yorgos Lanthimos, Povere Creature!, 2024

© 2023 searchlight pictures. all rights reserved. property of searchlight pictures

Bella’s odyssey begins in a surreal Victorian London infused with contemporary nuances, her lavish home decorated with eccentric furniture, oversized chairs, ceilings decorated with colossal ears, her father’s whimsical inventions, and a garden inhabited by hybrid creatures – chicken-bodied, bulldog-headed pets. As she ventures beyond, her travels take her from Lisbon to Alexandria to Paris and back, initially bathed in vibrant colors before descending into darker realms as the realities of the world unfold.

The transition from vibrant hues to darkness almost chiastically reflects the progression from early monochromatic scenes to full-color landscapes. Art Nouveau intertwines with steampunk, pushing organic and anatomical elements forward in a frenetic collage where Brutalist architecture converges with the universes of Schiele, Bosch, and Bacon. A visual amalgamation culminates in an idealized queer garden, a sanctuary where a liberated coexistence of styles and characters thrives – a departure from Dogtooth’s oppressive environment – where one can pursue study and enlightenment serenely, devoid of coercion.

7. How deep is your labyrinth: the triple New Orleans of Kinds of Kindness

One and Three is the New Orleans that Lanthimos chooses for his return to collaboration with Efthimis Filippou, former co-writer of Dogtooth, Alps, The Lobster and The Sacrifice of the Sacred Deer. The reunion brings the director back to turn his disenchanted and sadistic gaze on a humanity struggling with the dynamics of freedom and submission, fiction and reality. One and Three is also the interpretation of Emma Stone, Jesse Plemons, Willem Defoe, Margaret Qualley and Hong Chau, who, in the three films that revolve around the MacGuffin R.M.F. and make up the macro-film, play different characters whose actions are nevertheless united by the impossibility of exiting the labyrinths that the Greek director reserves for them, trapping them in a mythological universe articulated in the visual dimension of the most typical American indie cinema. Three stories, three declinations of relationships of dominance and submission: at work, in a couple, in the religious sphere.

Lanthimos dissipates the cadence of framing with a redundant approach to environments, attacking his puppets with shots that make them appear passive, whatever action they perform. Environments that reinforce the immobility of the characters' fate. In the first episode, it is the skyscrapers of the Central Business District and the sumptuously furnished mansions of contemporary American upper-middle-class style that encapsulate Robert's (Plemons) subservience to his boss, Raymond (Defoe), the 'director-god' who oversees each of his mini-films.

View gallery

View gallery

In the second episode, we move to a suburb immersed in nature, with humble wooden houses surrounded by trees naturally decorated with air plants that float suspended. Here lives Daniel (Plemons), a police officer who has moved to live with Liz (Stone), a researcher lost at sea who returns after months but whose identity does not seem to convince her husband, who subjects her to increasingly atrocious home tests in a deadly paranoid spiral.

The third episode takes place in the motels and on the roads of Louisiana, crossed at high speed by the already iconic eggplant-colored Dodge Challenger driven by Emily (Stone) in the compulsive search for a healer (Qualley) to be delivered into the hands of a sect founded by the gurus Omi (Defoe) and Aka (Chau). The center of the labyrinth and the common denominator of the locations is the hospital, to which all the characters return in some way, and for different purposes, in the various episodes. While the colors - red, blue and yellow - of the hot dog stand in the epilogue give the titles their chromatic tripartition.