This article was originally published in Domus 1052, December 2020.

Itali’s decree of the 3 November 2020 has once again imposed a (temporary) nationwide closure of cultural spaces. This is yet another act during the Covid-19 emergency that stresses the distinction between interior and exterior space: the former problematic, the latter curative (or at least safer).

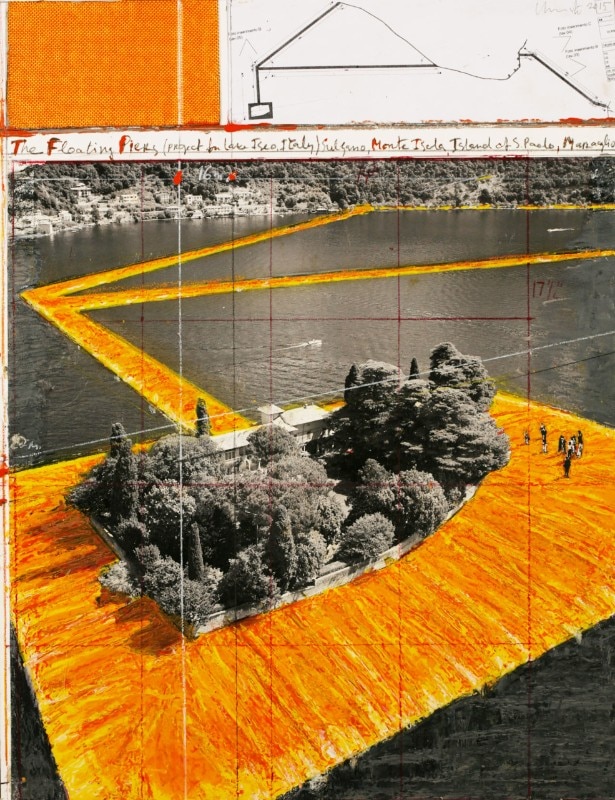

Nothing new on the horizon compared to what happened in other epidemics recorded in history, when isolation in the countryside was the alternative to the shared space of the city. In this sense, the great interiors of museums – not to mention houses, subways, trains and aeroplanes, which we frequented and boarded quite naturally until a year ago – are being undermined by their own spatial condition. From places of preservation and optimal enjoyment, interiors have become inaccessible, hence a system of imprisonment and exclusion. There were already signs of a return to the environment in art before the pandemic turned up and constrained our reality. Suffice to mention the monumental work of William Kentridge in Rome and of Christo on Lake Iseo. In 2016 the South African artist reverse-stencilled an imposing mural procession titled Triumphs and Laments on the walls lining the Tiber, by removing parts of the black dirt that had built up on the stones. In the same year, crowds of visitors walked on water courtesy of Christo’s The Floating Piers. Each certainly unique and conceived by a single artist, these two environmental works highlighted existing architectures and geographies.

In this strange summer of 2020, two projects took shape “without an interior”: an exhibition and a floating cinema. Featuring installations and films usually presented in interiors functionally designed to host them, these initiatives flipped our perspective by presenting their contents out in the open. Both experiences responded to the limitations imposed by the emergency, translating them into characteristics that already belonged to these specific places: a large summer residence and a fragment of Venice’s lagoon, whose configurations meant adapting to the architecture of the environment.

The imposing Villa Imperiale in Pesaro, with its park and some rooms left open, was taken over by the exhibition “Against Sun and Dust”, curated by Cornelia Mattiacci and Alessandra Castelbarco Albani (20.8-3.10.2020). The exhibition’s setting was an active part of the scene, and the works on display were devised to reread the villa’s dense spatial and temporal stratification. The original core of the complex, commissioned by Alessandro Sforza, was completed in 1469. In the following century, Francesco Maria Della Rovere and Eleonora Gonzaga invited the architect Girolamo Genga of Urbino to restore and extend it. The 16th-century wing, laid out on the hillside with a system of terraces, is defined by loggias, gardens, courtyards and open spaces (recalling the courtyard of Bramante’s Belvedere and Raphael’s Villa Madama). It culminates in an articulated terrace, from which a new and different landscape emerges, with architecture and trees competing at a distance. The exhibition’s title references and reinterprets the inscription on the courtyard wall of the Rovere wing that reads “pro sole, pro pulvere”. The visit was organised to reverberate with the motivations that inspired the creation of this summer theatre of leisure en plein air, erected “to compensate for the sun and dust” and the military life programmatically left outside its walls. Site-specific works marked the exhibition route, juxtaposing and appropriating the villa’s spaces and periods with the contemporary languages of the visual arts, literature, architecture, design and music. The experience of the place was therefore also a discovery of the reflections overwritten on it through time. Wandering around it was like a treasure hunt where the destination and path were both parts of the story. The works were exposed to the changing light and falling leaves, and visitors were plunged into a maze of narratives.

“Unknown Waters” was the title of the initiative by Edoardo Aruta and Paolo Rosso (Microclima), which spawned a floating cinema in Venice last summer (27.8-5.9.2020). Conceived as a way to rethink the city starting from the lagoon, the project was supported by some of the most important cultural institutions active in the historic centre. It was an opportunity to work together to create a new place exposed to the tides and winds. Two floating platforms were built in the shallows behind the island of Giudecca, by the Rio de Sant’Eufemia: one for the projection equipment and the other for the audience. Spectators could also watch from their own private boats, anchored in a designated area. The screened films included stories by local and international directors and artists, both historical and contemporary, such as Zbigniew Rybczynski’s Tango (1981), Peter Greenaway’s Making a Splash (1984), Caterina Erica Shanta’s A History About Silence (2018) and Antoni Muntadas’s In Girum Revisited... (2016). Clearly, the films were shown at night, in darkness, to give substance to the projections. The project sought to inhabit the lagoon and make it accessible even to those who do not own a boat, transforming an open space into a cinema.

Floating or amphibious architecture is a Venetian archetype. Etched in the memory is Aldo Rossi’s Theatre of the World, created in 1979, as well as the Pink Floyd concert in 1989, and the beautiful Croatian Pavilion designed for the 12th International Architecture Exhibition in Venice. The latter never reached its destination, after collapsing while crossing the Adriatic in 2010. Building in the lagoon implies dealing with the stack of rules that define the ways of using it, along with the technical problems dictated by instability and motion, and with an extended horizon in contrast to the compact mass of architecture in the historic centre. These were the uncharted waters that were fitted out as a cinema-laboratory for a few nights. Located outside the city that invented quarantine, it was an experimental space in the lagoon that was once dotted with leper hospitals, and where people rethought the relationship between construction and environment, between the real and the imaginary.

The exhibition and the floating cinema directly engaged with the shadows of trees, the wind and the water. Sometimes the scenes of reality surpassed those of fiction. One evening in Venice saw a Werner Herzog film having to compete with the rising of a large red moon amplified in the waters of the lagoon, distracting many viewers. For architecture one note remains: the urgency to reopen, to build new alliances with the exterior, which should be seen not just as a horizon to be framed but as a living and changeable material with which to coexist. In other words, to face up to the return of the environment.

Sara Marini (Urbania, 1974), architect and PhD, is full professor of architectural and urban composition at the Università Iuav in Venice. Since 2020 she has headed the Iuav research unit for the PRIN national research “Sylva”.

Opening image: a film being shown in the “Unknown waters” festival in the Venetian Lagoon, 27.8-5.9.2020. The initiative, by Edoardo Aruta and Paolo Rosso, was developed in collaboration with Ocean Space/TBA21−Academy, Pentagram Stiftung and Palazzo Grassi - Punta della Dogana, Pinault Collection. Photo Chiara Becattini