Dutch borders

by Robert Such

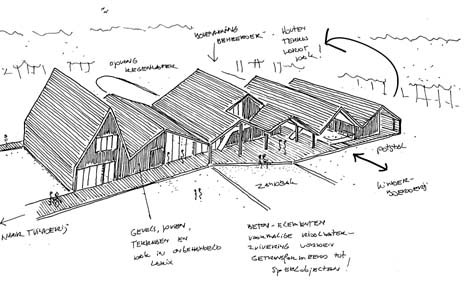

In summer, trees screen the Mikkelhorst ecological farm building from the neighbouring residential houses to the southwest. In the colder months, gaps between the wintry skeletons reveal the wooden structure to passers-by. The bare tree trunks become bar lines, visually punctuating at regular intervals the zigzagging line of pitched-roofs. Designed by Dutch practice Onix, the eco-farm for the disabled is located near Haren, five kilometres south of Groningen. In this northern region of the Netherlands winters are harsh. But to the eye the natural materials used in the making of the eco-farm impart a warmth that one appreciates on arrival. Up close, one sees deep reds, greens and blues in the wood beneath the sheen left by the rain. From the adjacent fields the architects appear to have built a row of terraced buildings. Viewed from the northwest, the picture is different.

The eco-farm resembles a barn, and a partially dissected one at that. In plan view, the pitched roofs at the south end have been sliced into diagonally. At ground level one sees both ridge lines and a cross-section at the same time. It takes a moment or two of walking around to resolve this visual conundrum. Rather than remove all trace of the water treatment plant that had been bulldozed to accommodate the construction of the eco-farm, Onix incorporated the in-filled concrete basins into the work. The main axis of the longest basin and the long axis of the building now meet at a right angle. This juncture, one edge of the basin in fact, delineates the border between the people-oriented spaces to the north and the animal stalls to the south.

In 2001, Onix referred to establishing such a link between site and architecture in the practice’s DogmA 01 rules. “The design must be made specific for the location. No pre-designed parts or details must be used”, is the first rule of the Vow of Chastity, a tongue-in-cheek mission statement that is the practice’s contribution to the debate about regional-specific architecture in the Netherlands. Onix aims to construct buildings that are never isolated objects, while making “durable and low-maintenance architecture that ages gracefully”. The DogmA 01 manifesto embraces non-standard architecture, and rejects, among other things, facadism, historicism, catalogue architecture and pure digitally-designed architecture.

Rules seven and ten have practically the same wording as Danish filmmakers Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg’s Dogme 95 rules, on which Onix’s rules are based. Disappointed with mainstream, particularly Hollywood, films, Von Trier and Vinterberg published their list of ten rules in 1995. In the previous year Haiko Meijer and Alex van de Beld had founded Onix. The name derives from ‘Generatie Nix’, which was coined by the Dutch writer Rob van Erkelens. The etymology of “Onix” goes something like this: Generatie Nix is the Dutch equivalent of Generation X . “Generatie Nix” is also referred to as the “Nothing Generation”. From zero, or 0, Nix, one arrives at Onix. Onix assembled the eco-farm’s various functional spaces that the client (the Foundation Ecologische boerderij De Mikkelhorst) specified in the brief – a children’s zoo, a garden market, offices, changing rooms, a tea room, a kitchen, a stable and a barn – under one roof, creating what it calls a “roof-top village”. It is one building that can be read as a collection of buildings.

A feeling of spatial and material continuity runs throughout the work. While the wooden walkways that skirt the front and the rear of the structure allow wheelchair access, behind the building the wooden surface abruptly turns upward at the point where building and sewage basin cross paths. One has the impression of an envelope having been cut and folded. The form of projecting metal gutters further enhances the folded aspect of the building, which has multiple entry points from which to begin exploring. The main entrance on the southwest side leads into the entry hall and the reception area beyond. Here, inside, the sloping wooden roof is visible high above – there is no false ceiling to hide it from view – and the high east-facing windows opposite create a large, open and well-lit space. Turning left out of the eco-farm’s reception takes one through a number of rooms, including the farm shop, that are connected by insulated sliding partition doors.

Above these rooms are the offices. Returning to and passing through the reception area, one enters another set of rooms that include the tea room, activity room and changing rooms. On leaving the changing rooms disabled users move outside to visit the animals in the stalls, which are connected by a covered boardwalk. On leaving there is the familiar tug of a place that has left a positive impression. This is not spectacular architecture, but it is a space one could enjoy working in. And since Onix wishes to construct buildings that “age gracefully”, it would be nice to return to the farm in a few years to see how it has matured.

The new ethics of caring

by Patrizia

Mello When we cast our minds to the subject of the disabled, our most immediate reference is a closed place with boundaries created around a personal state to contain a type of physical or mental complaint. This architecture is not usually very cheerful and ends up producing a certain distance in one’s behaviour and rituals. The functions conjured up by the spaces are not very stimulating either, as they lack references to “normal” everyday living. These care facilities are designed for brief stays, with no particular attention paid to the life that will be lived inside.

The Dutch group Onix proposes a highly unusual solution for the type of spaces needed for disabled patients. These patients live with different types of disability – they are visually impaired, in wheelchairs or have mental problems and their age can varies from 18 to 60. The type of architecture created is a neutral receptacle, constructed using natural, untreated materials, where patients can, over a whole day, rediscover living rhythms that are in perfect harmony with the surrounding nature. From the outside, the farm appears to be made up of different volumes. But the interior has a continuity of large spaces opening onto the exterior, all linked to each other. The residents can move about freely, without the burden of finding themselves in a closed space or having to cope with traditional architectural barriers.

In order to facilitate the orientation of visually impaired patients, graphic artist Peter de Kan will complete the finish on the inside floor by marking all the spaces with a blue colour, which is also easily identifiable and recognisable in the evening. Here, the inhabitants will once again feel useful. The principal ecological message is using farm spaces to spend time together, growing organic produce and selling it to the public and caring for the animals. The aim is to allow the disabled to perform enjoyable, relaxing activities, during which there is constant contact with nature, thanks partly to large picture windows and a patio in front of the structure. These spaces – equipped with few furnishings to facilitate movement – enable people to feel integrated and, at the same time, protected by the “natural” type of architecture and the suggested life rhythms.

What better place than a farm to help you perceive the simple life and reconnect with your inner self? Another important element that completes the “ecological” message of this project is the perfect integration between the farm and life in the nearby towns. While the patients conduct domestic rituals, which are educational and “curative” for their minds, the adults and children from the local area can come to visit the farm, play with the animals and encounter a world similar to the one we see on a daily basis. The project also aims to gradually integrate the “pathological” into a normal existence. The Onix farm is a point of departure.

It inaugurates a different attitude, one of a greater understanding of the disabled. Neutral environments combine with the use of warm protective materials such as wood, facilitating one’s orientation through spaces with different functions as well as through the specific nature of a place fixed in the common imagination, namely the farm. These are all aspects that create an alternative microcosm to the better-known hospital structures for the disabled. Moreover, the simplicity of this microcosm clearly conveys the passing of time to the inhabitants and helps them psychologically to rediscover a sense of purpose in their lives. And that is something far better than any therapy.

With Titano, design meets performance

The Titano aluminium range by Oknoplast continues to stand out thanks to its high-performance and minimalist design — especially when combined with the Lunar Square handle.