Asking “what a profession can do” is an interesting litmus test for gauging the degree to which a professional practice is universally understood and defined. Ask what dentistry can do, or accounting, and you’ll get some funny looks. Isn’t it obvious? But what can design do? The enduringly ambiguous word and its recent trend as a suffix to almost anything — business design, network design, relationship design — makes it perfect fodder for existential interrogation.

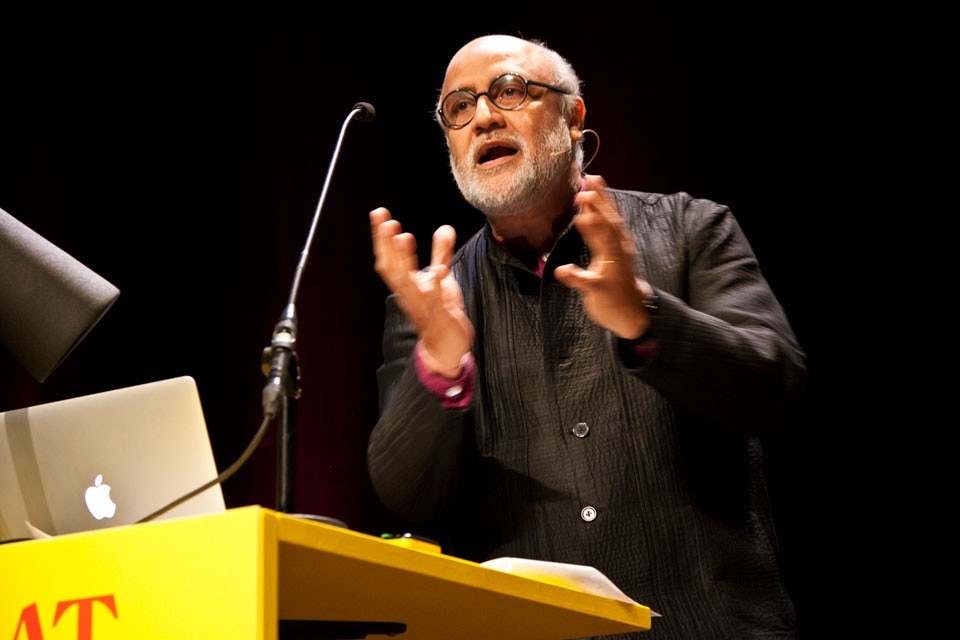

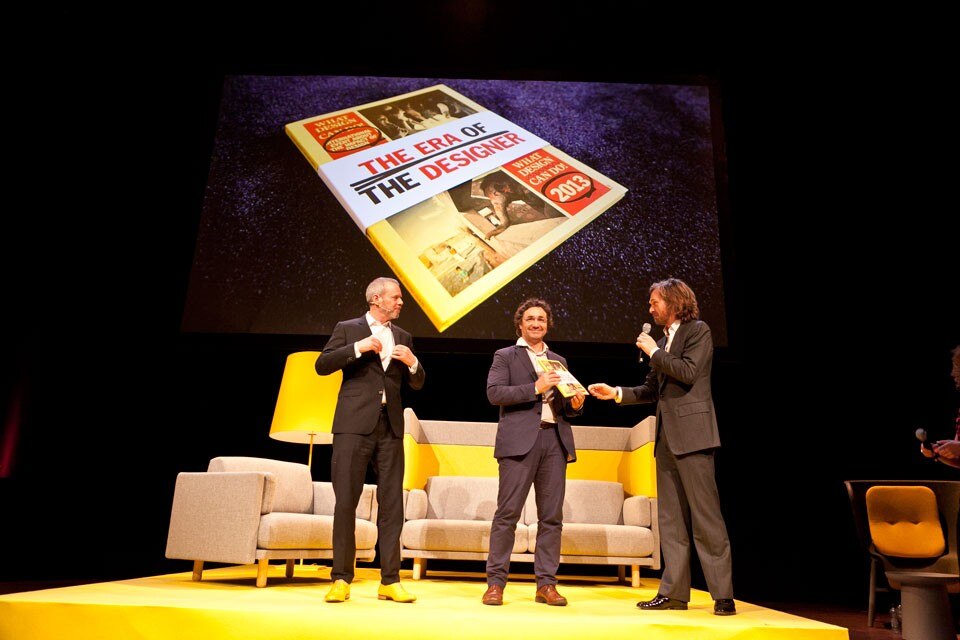

Enter What Design Can Do (WDCD), a two-day conference held every May in Amsterdam that attempts to answer that question by pointing to an expanded field of agency and outputs. The event consists of speakers, workshops, and plenty of networking opportunities. It also has big ambitions: conference founder Richard van der Laken hopes that it becomes “the biggest multidisciplinary design conference in Europe, with an international audience.”