The catalogue accompanying the exposition of the permanent collection at the Design Museum's new building in London is expected to reflect the institution's programmatic approach. Hence in its perusal, the central question regards the direction that the entire museum has chosen to follow, and more generally what the function of a design museum might be today.

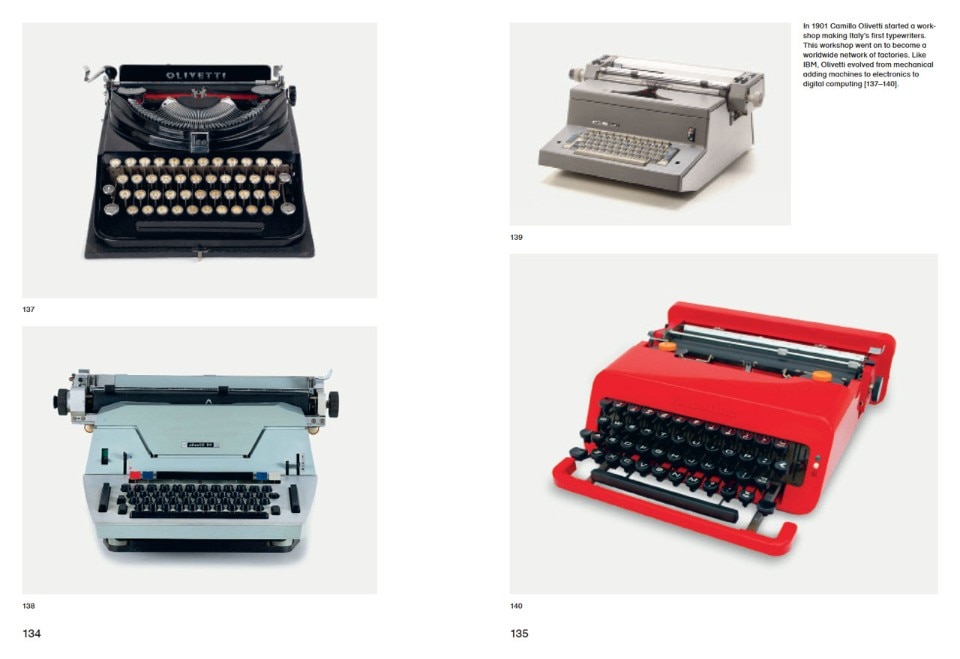

Upon reading, the catalogue leaves several of its discussion subjects open. The principle one, as mentioned, regards the museum’s general cultural strategy. What emerges is only an indirect answer to the question that opens the first chapter, “What is design?” The solution adopted here is that of selecting answers coming from many agents of the discipline: designers, manufacturers, curators and critics. And it is symptomatic that when Paola Antonelli, the senior curator of the New York MoMA (one of the Design Museum’s main competitors), is quoted, the catalogue underlines her bias for speculative or anonymous design. In effect, the Londoners’ choice seems to tend toward a more classical definition of design, the kind that traditionally is called Industrial Design. The mass-produced product, or the product conceived for the masses, remains an important design discriminant.

Which is not to say that the London Design Museum does not conduct research as one of its activities – on the contrary. Its programme “Designs of the Year”, one of the liveliest on an international level, involves experimentation and the promotion of young talent. However, it is only one element of the wide range of initiatives organised on a yearly basis. The range is wide, because the museum's ambitions regarding visitor numbers are big. In this sense, the slogans it uses on the website are eloquent: “Design is a way to understand the world and how you can change it” is one. This is an inclusive and extremely open way to create a dialogue with the public at large. Then again, historically seen, this is a typical, established way of behaving in the English design culture. Not by coincidence, one of the most quoted theoreticians in the catalogue is Henry Cole, a deus ex machina of design in the English-speaking world and a reference point for any historical dissertation on the subject.

Simultaneously, Cole created the first large international trade show of design (the 1851 Great Exhibition); ordained the United Kingdom's design schools; founded the first nucleus of the Victoria and Albert Museum; and headed the most important design magazine of his times. This meant uniting in a single professional figure the critic, the curator, the teacher, the design expert and the political consultant. In short, he represented everything taking place in design behind the scenes. This picture allows us to understand how a product is part of an integral process in which design has ties to the economy, politics, customs, philosophy and the culture of its times.