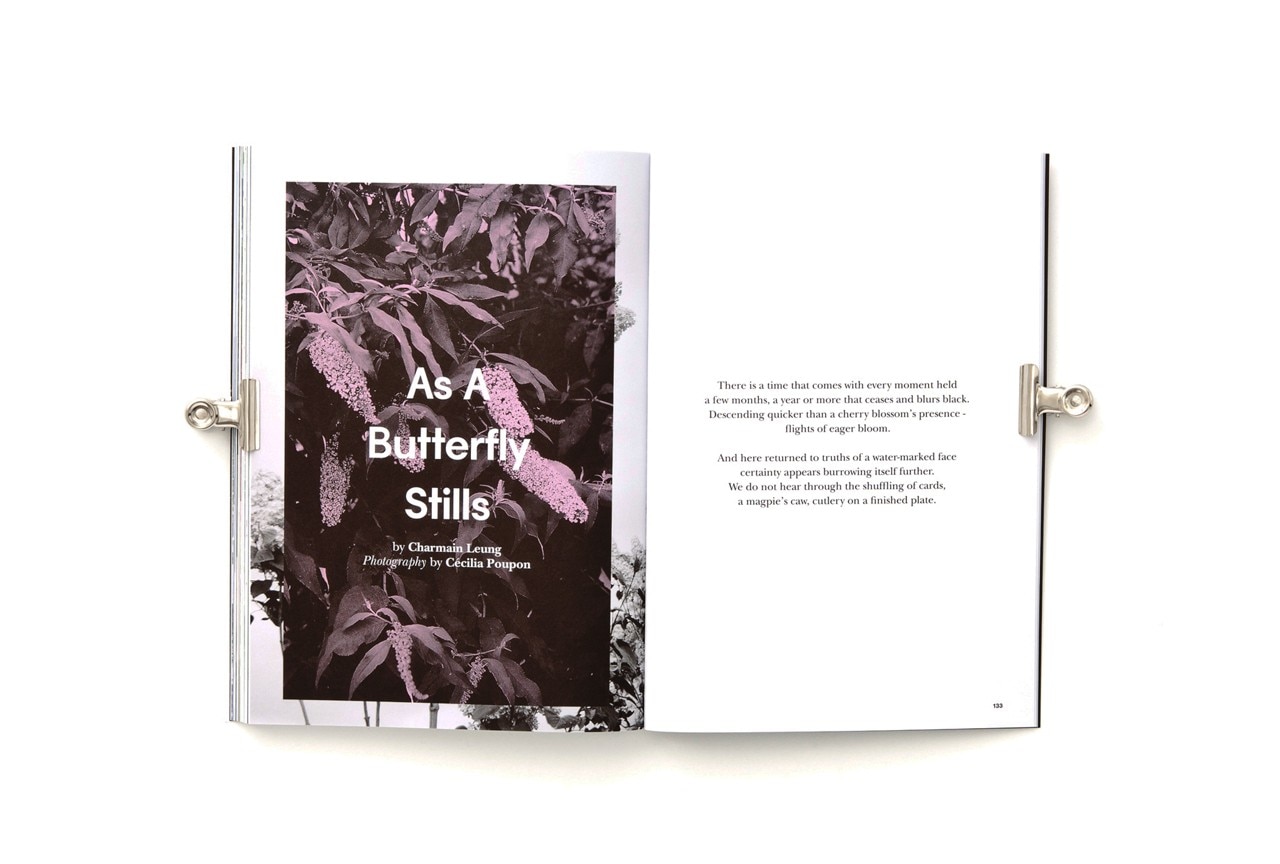

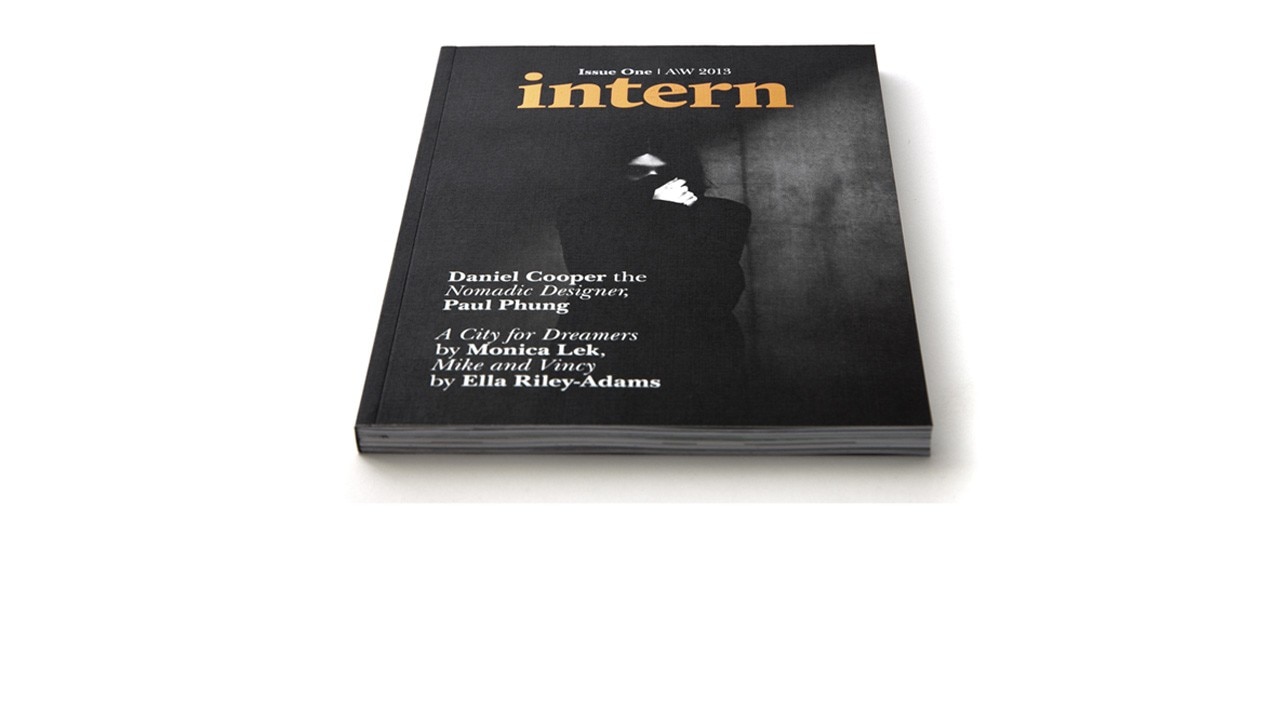

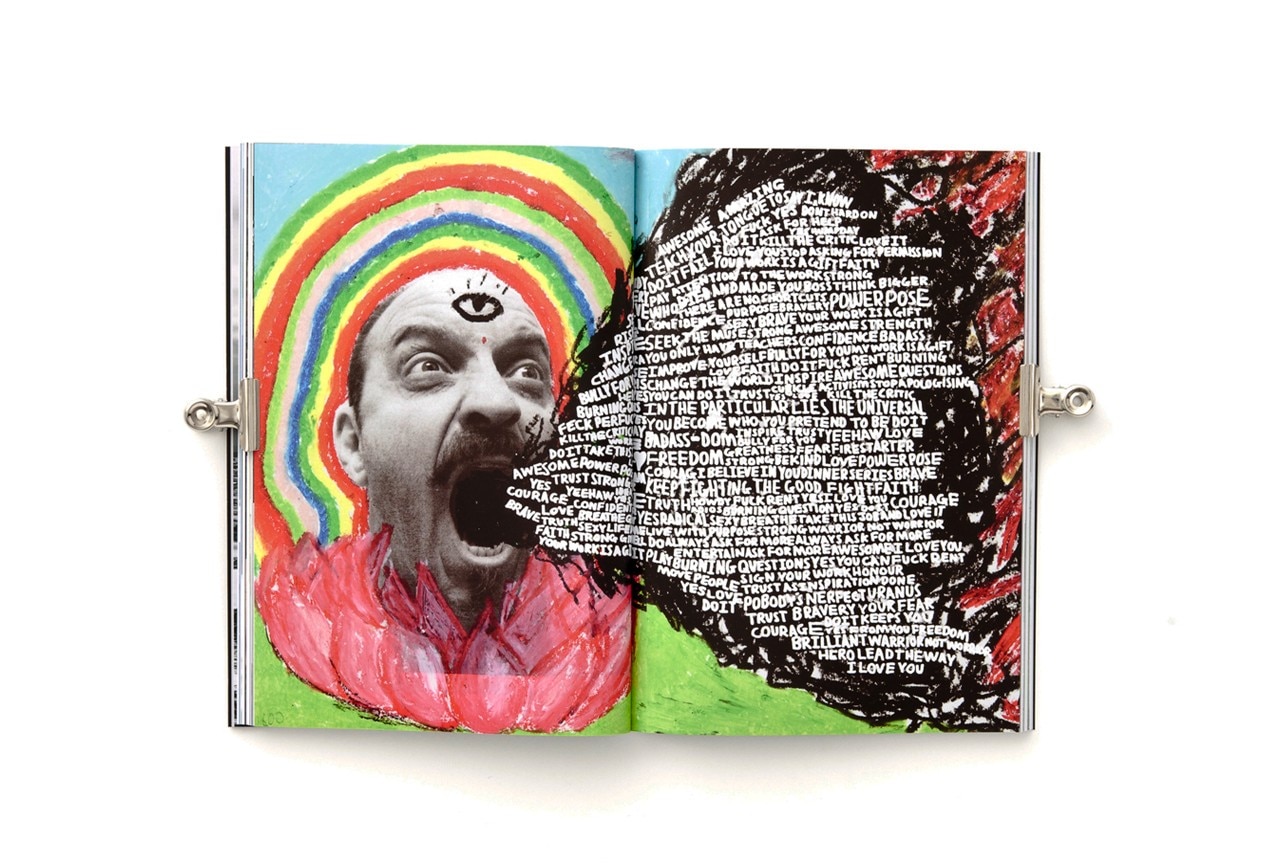

Financed through crowd sourcing and now at its Issue Two, Dudson’s editorial project tackles the invisible social and moral issue of unpaid work in creative industries. Beyond publishing a beautifully crafted magazine, that features the best crop of emerging creative talents, Dudson’s proposes a self-reflecting opportunity which aims to stimulate debate on this current issue.

Here below are extracts from a conversation we had with Dudson that capture the story behind the inception of Intern and frames a provocative snapshot on what he found in the grassroots of the creative internships world. The picture that emerges throws open a series of questions that go well beyond the contents of the magazine itself. Particularly, they make one reflect on how a new generation of creative talents – which are emerging in a period of recession – produce high quality work, yet have little pecuniary expectations.

Gian Luca Amadei: How did you get interested in print publishing?

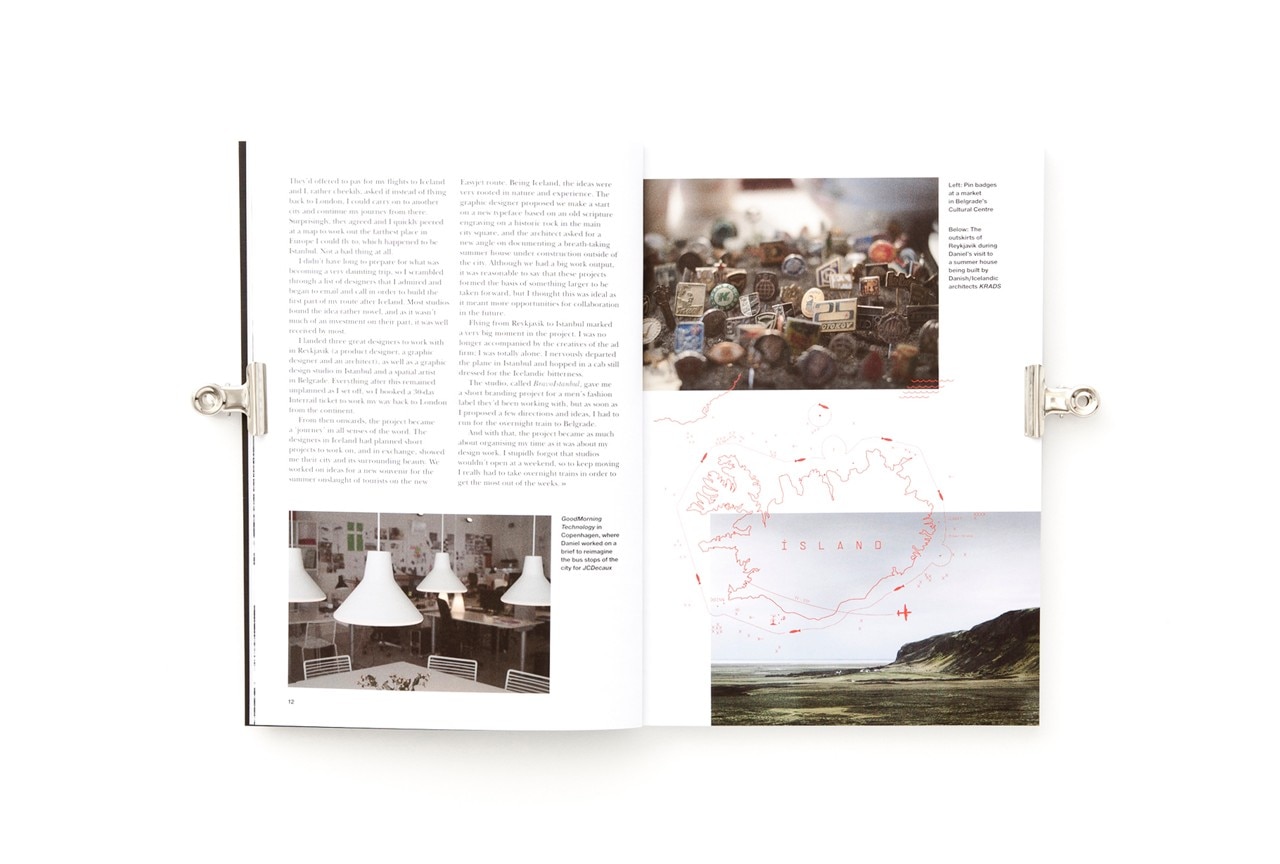

Alec Dudson: It started when I returned from a two-month trip around the US after my Masters. I had heaps of photographs and a friend was just starting up a new website and asked me to join. That became a platform to disseminate my work online, that eventually it evolved into an editorial project. After nine months I started hunting for internships with publications that I really admired. I guess at that stage, I was looking to figure out if this hobby was something that could become a career.

G.L.A.: How did you come up with the concept for Intern, what were your aims for it?

A. D.: The idea was to put something together that could represent this burgeoning class of workers while also demystifying the world of internships for those in or around it. The concept for Intern was something that I spent a while contemplating. No matter what other ideas I played around with, this one about interns kept coming back to me.

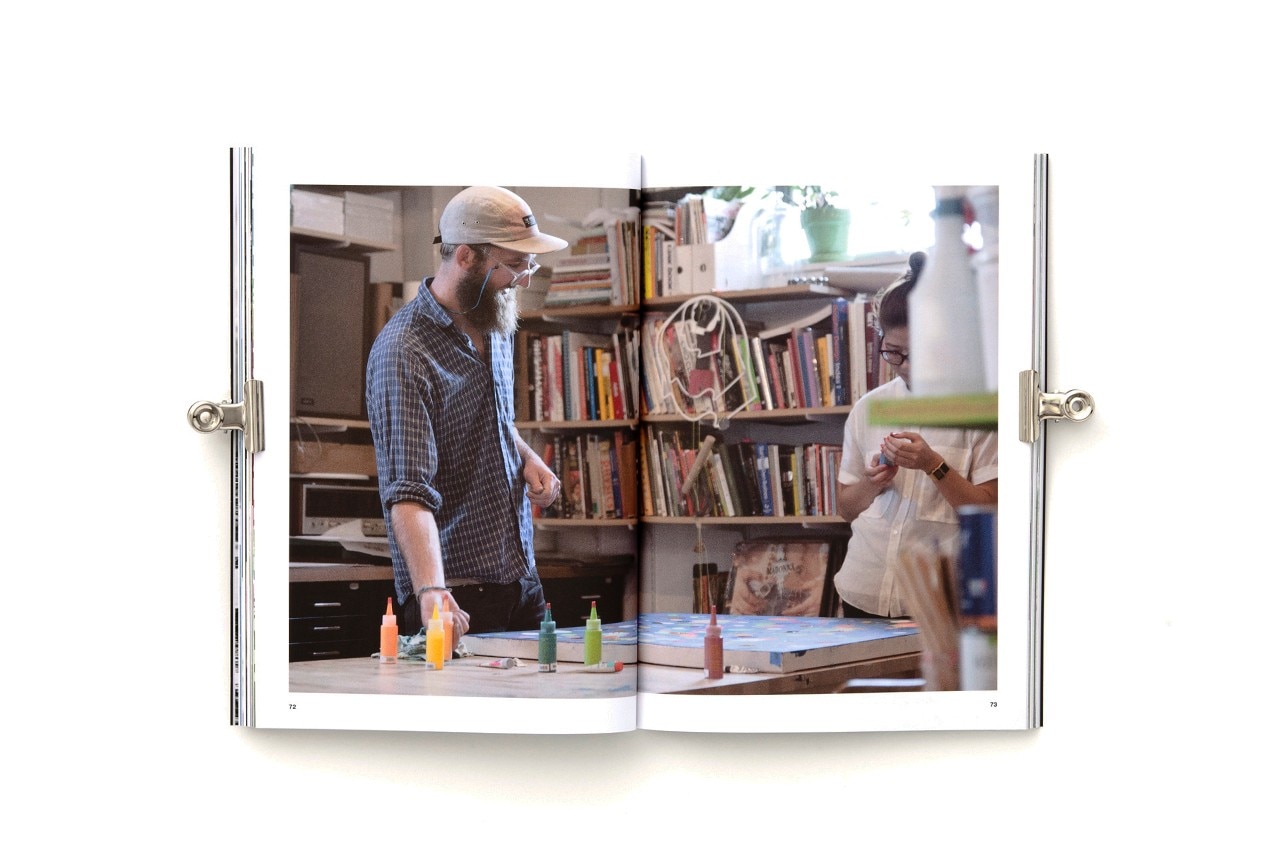

G.L.A.: Could you tell us something about the process you use to put each issue together?

A. D.: Once the concept was outlined, the biggest challenge was to decide on the tone of the magazine in terms of its contents. For Issue One, I sourced the content myself, finding contributors at the right stage of their career to feature. The selection criteria I adopted were based on the question: are these interns and students or otherwise working in the creative sphere unpaid? If that was the case, I checked their work and ideas and see how they could contribute to the issue. For Issue Two, however, we decided to open up for. While this is a bit of a step into the unknown, will allow for contributors shape the sort of angles and issues we cover.

G.L.A.: Tell us more about your experience with crowd sourcing?

A. D.: Our Kickstarter campaign had a great response and has been key in the magazine’s success to date. One of the positive aspects of crowd sourcing is that it gives individuals or start-ups the chance to see their idea come to life on their own terms. Another huge positive for us was the press coverage that the campaign attracted. Essentially, that allowed us to establish the brand all around the world and tap into what would become our initial readership. In terms of disadvantages, it’s nerve-racking, but I suppose any means of raising initial capital would be.

G.L.A.: Why not a digital magazine?

A. D.: I will always be one of those people that appreciate a photograph when it is displayed in a gallery or printed on a page, far more than on a beautifully designed website. Although print publishing is a difficult industry, there is a great independent mag scene at the moment, as there are plenty of purists of around like myself. That said, we will be releasing soon an iPad edition of Issue One. Digital can’t be ignored, but I see it as a companion format to our flagship print endeavour.

G.L.A.: How are you going to make the magazine economically self-sustainable without compromising your editorial integrity?

A. D.: We operate on a sponsorship framework. Currently there are eight sponsors per issue, we design the pages in-house so that they don’t disturb the flow of the publication and so our readers feel more inclined to check them out. It is still considered an “ideal” to have no advertisements or sponsorships but I have to prioritise and my first priority, is to pay my contributors.

G.L.A.: How does intern fit within the existing editorial landscape?

A. D.: I hope that intern has given the tens of thousands of people working in creative internships something that they can identify with. So many magazines today take on interns who do far more behind the scenes than they are recognised for. I felt that something that made them centre stage was severely lacking.

G.L.A.: What is the current debate about internships?

A. D.: It’s the lack of debate that needs addressing at the moment, we’re doing our bit to try and keep the debate constant, rather than something that the press picks up and subsequently dropped when they deem it to be ‘newsworthy’. The big challenge at present though, is changing the attitude of students and graduates. They think nothing of working unpaid and that creates a problematic situation. Personally, I think this is a morally perplexing situation for the design world: gentrification can only stand to restrict creativity.

G.L.A.: Your position is a privileged one being in direct contact with so many creative emerging talents, which changes do you see emerging in the role of the architect and the designer?

A. D.: Contemporary culture is making many young people tremendously resourceful and that is always a quality that will work well with both design and architecture. Although architecture, in the UK at least, has brought internships under control to a degree, I wouldn’t be surprised if collectives will start to form, much like they have in the design world. If young people’s regular route into their chosen field is blocked, some will find an ad-hoc solution. It happens time and time again in history and the current wide-spread nature of internships is just the sort of thing that could inspire that kind of action.