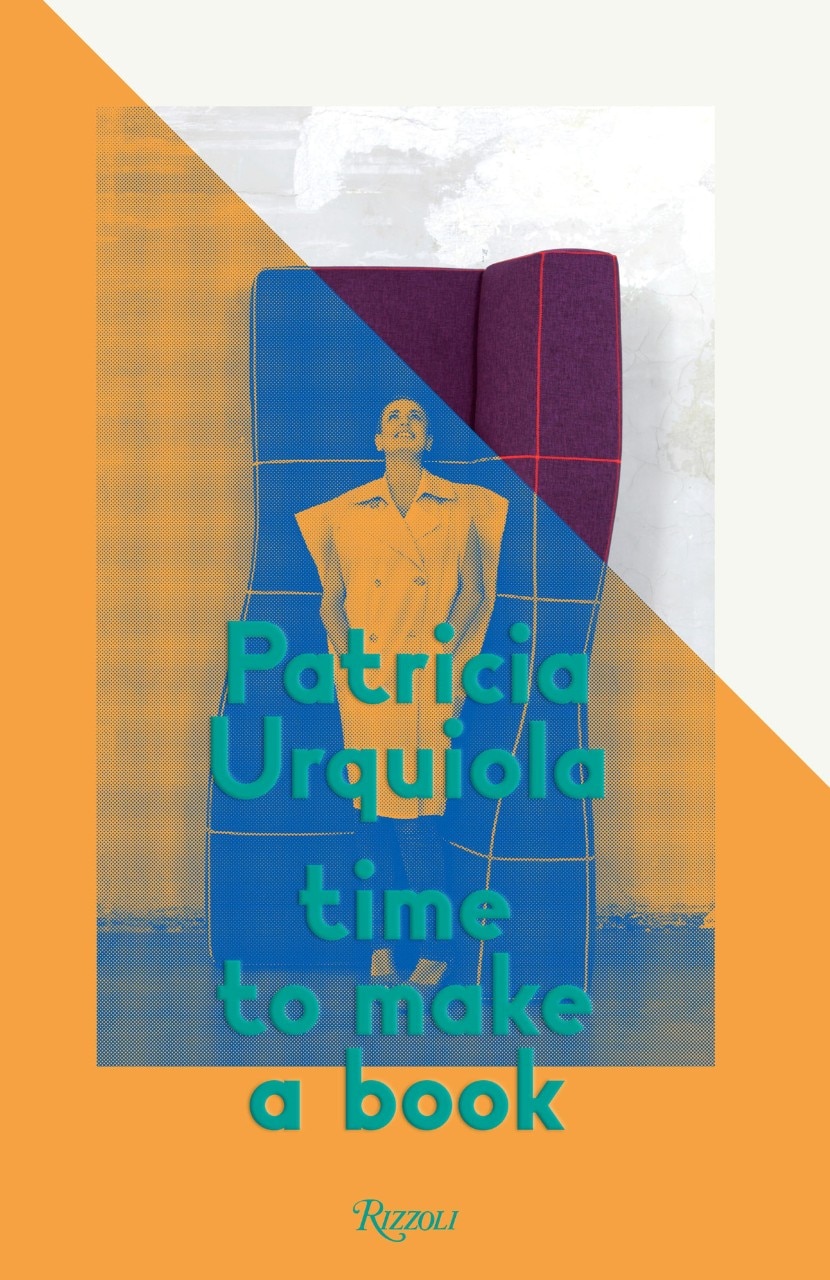

The first monograph to present the rich and multi-faceted work of Patricia Urquiola already reveals a declaration of intent in the title: to seize the day, the moment and the time necessary for a deeper look at her work, to lay down in black-and-white the milestones in an articulated journey. Most of all, to open up many doors and spark off many ideas and many interpretations for the future. To, indeed, make a book, where in the term “make”, so in keeping (and so present) in her work as a designer one can perceive the direct continuation from the mind to the hands, from the idea to the thing. The “thinking with the hands” that so effectively sums up the Spanish designer’s working method.

For Urquiola it is time to make a book “at just the right moment – in the historic caesura that the digital revolution will impose also on design” as Gianluigi Ricuperati so acutely grasps in the interesting essay that ends the book.

But at the same time, it has not been easy to define in the closed form of a book Urquiola’s complex, projective and many-layered work, little given to labels and categories. “I prefer everything to continue to grow, to not be finished. I prefer an open-ended narrative”. Like an antenna always on the alert, Urquiola is often ahead of the times with her avant-garde intuition and professional rigour, she dares to take directions that anticipate trends yet to come. Her working method is an experimental process that is at times tortuous, other times very quick.

For this reason, the book twists and turns through chapters – or rather conceptual stories – that bring together by affinity and analogy not only families of objects but also ideas, relationships and maps. Fragments of private life, journeys and quotations. It is only through this indivisible complexity that her work emerges, exuberant and consistent in terms of quantity, density and depth.

Urquiola is therefore not interested in presenting a chronological catalogue or even a hagiographic celebration of work that already enjoys wide critical acclaim but in creating a book that acts like a magnifying glass, examining themes that go far beyond the objects and things, a book that germinates, virally, new ideas.

In a rhythm that is “andante con brio”, woven with countless fils rouges, an original, iconographic account appears that demonstrates not only the Olympus of finished products but delves “behind the scenes” showing through more ordinary photographs of the work the uniqueness of the process, the phases of work and the many reconsiderations and adjustments that this kind of work implies. Patricia “folds, twists, models, coils, cuts and weaves” material, skilfully manipulates it to the point that it does not correspond, inventing forms that derive from the material itself.

At the end of the book is an essay and visionary conversation by Gianluigi Ricuperati who speaks of Patricia Urquiola’s “joyful restlessness”, tracing new points of view, amid selected reading, travel and visits home. “Patricia Urquiola has two different eyes, the first fixed on a solid, clear, well-known past; the second sees an electric and confused future, exiting and ready to be rethought”.