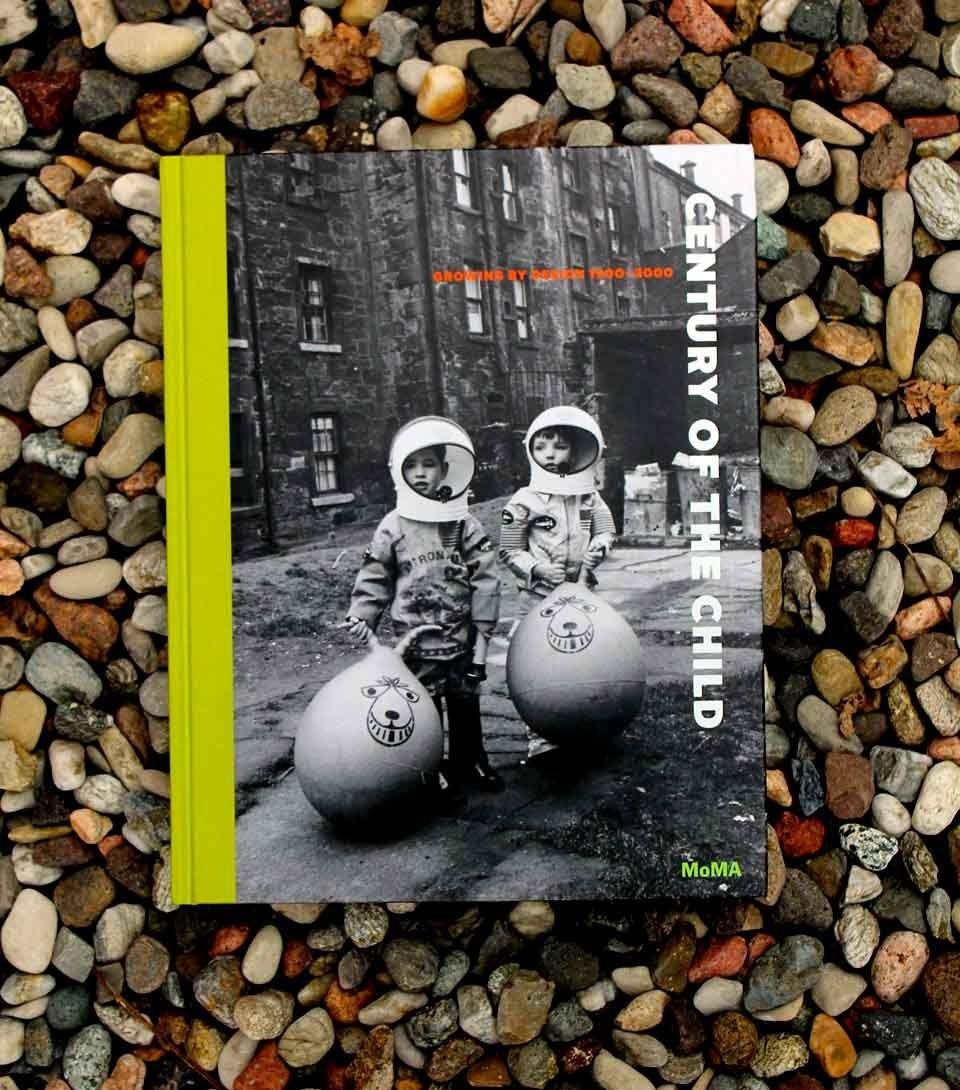

Between the 1900 publication of The Century of the Child, by Swedish design reformer Ellen Key, to the 1990 40th International Design Conference Growing by Design, childhood came from being regarded as a rigid, abstract idea anymore, to becoming an engine for the design tools of the 20th century. This evolution during a very rich century in ideological, social, political and economical changes is mapped chronologically in Century of the Child: Growing by Design, 1900-2000, an extensive, important volume on the many intersections of children and design, organised by MoMA Design CuratorJuliet Kinchin and Curatorial Assistant Aidan O'Connor on the occasion of the 2012 exhibition of the same title at the MoMA. With contributions by Tanya Harrod, Medea Hoch, Francis Luca, Amy Ogata, and Maria Paola Maino distributed through seven richly illustrated sections, the book seeks to advance the scholarly inquiry into the evolving relationship between childhood and design, tracking what Kinchin calls its "fascinating confluence".

At the beginning of the 20th century, society — and as part of it, designers and architects — began to slowly advocate that children are a good mediation between ideal and real; with their clean vision on everyday life, uncontaminated by social and cultural conventions, they will always elevate designers' thoughts to a better future.

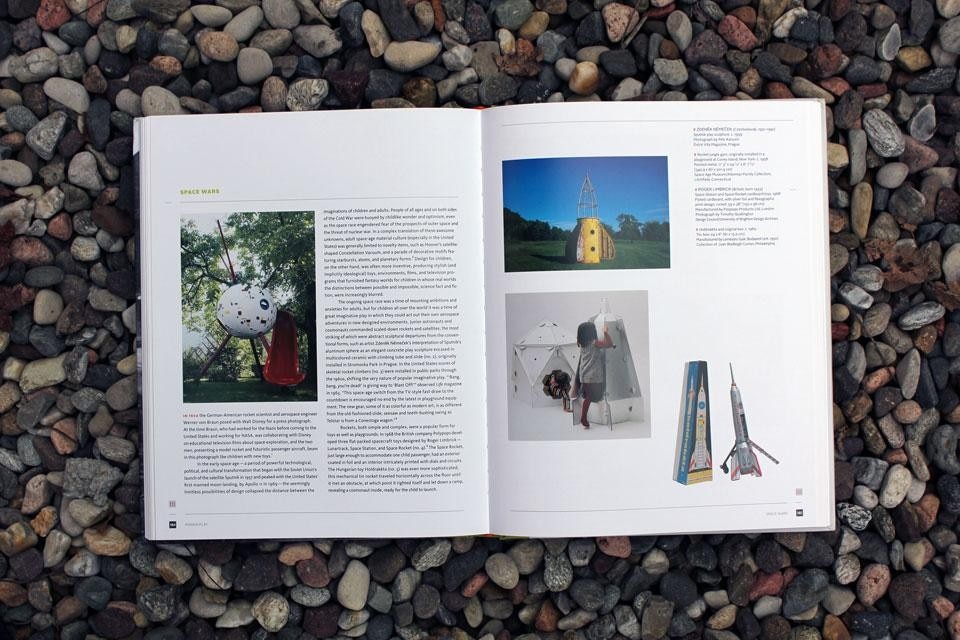

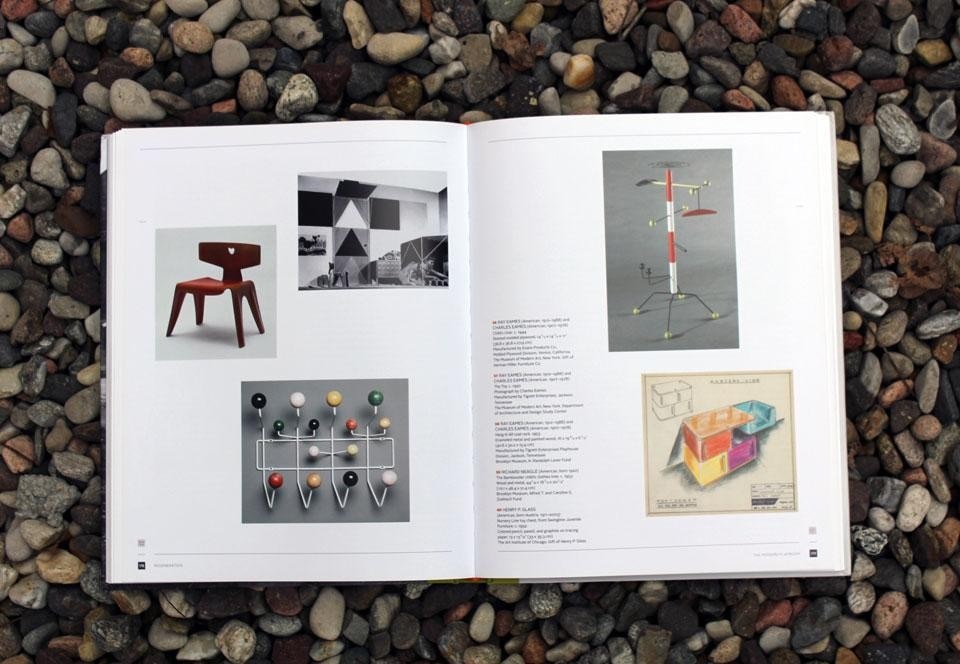

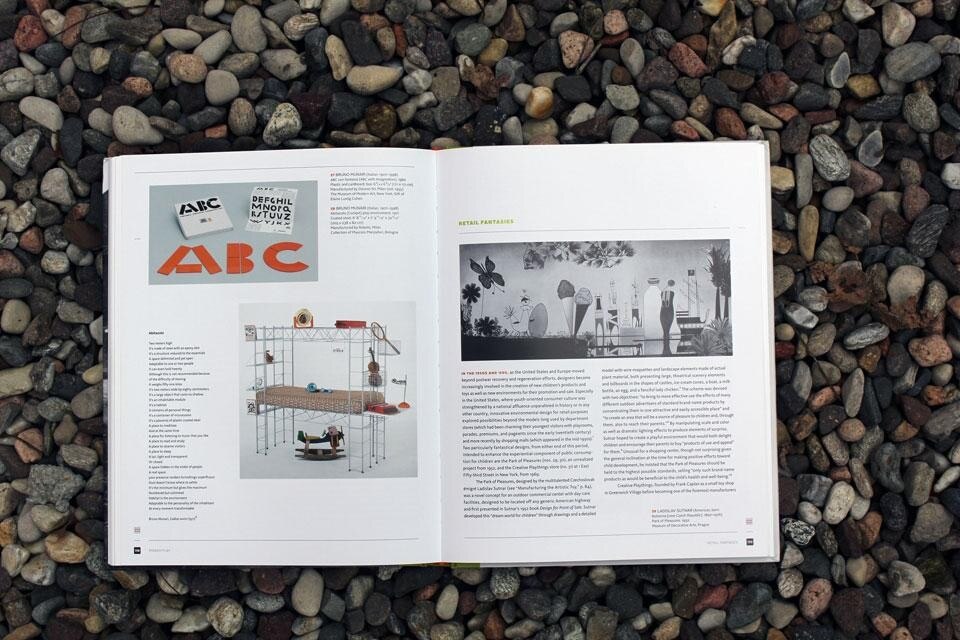

The creation of a learning environment for children was accompanied by a dynamic, inventive approach to the most important items in a child's existence: toys. As German pedagogue Friedrich Froebel remarked, "play is the highest stage of the child's development", and during the entirety of the 20th century, designers seem to have abided by this rule, creating many iconic exploration in toy design. While the first decade of the century was marked by interest on enriching the creative potential of the children through arts-and-crafts lessons, the following decades bring Swiss puppets and colourful, modern toys in Czechoslovakia, among many others.

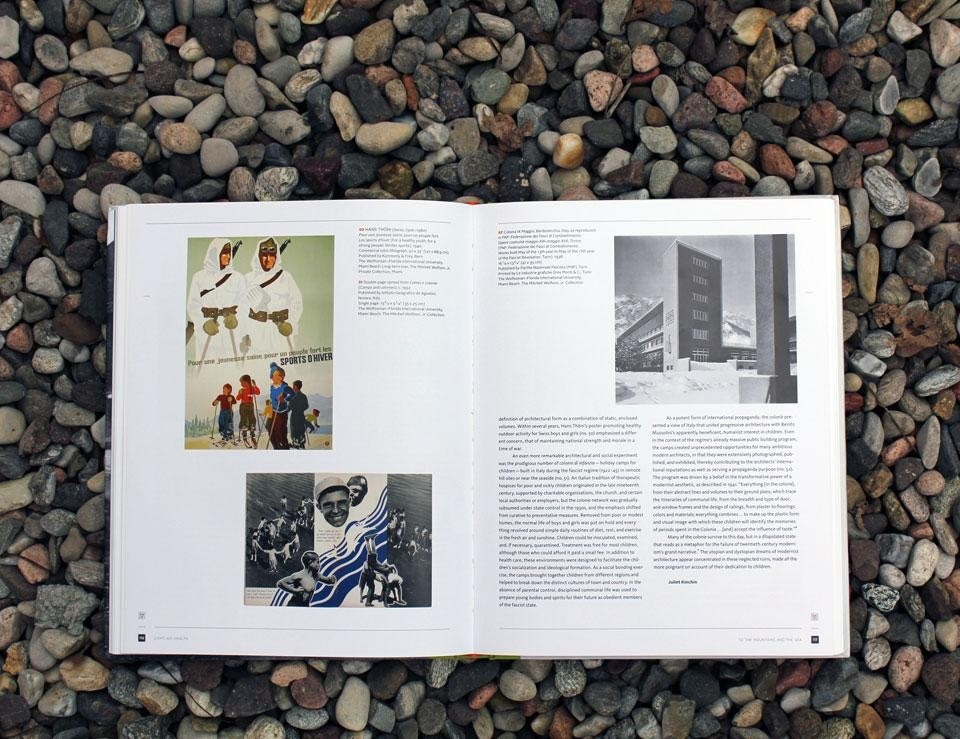

The educational paradox that arose in the years between the World Wars makes the reader aware that despite the reformers' wish to protect the child from the burdens of the adult life, the youngest were deeply implicated in the political events of the 20th century