In a dark time, the eye sees, as the proverb says, and Lucy Bullivant's latest book provides plenty of evidence that the most progressive architecture is produced in periods of economic and political crisis.

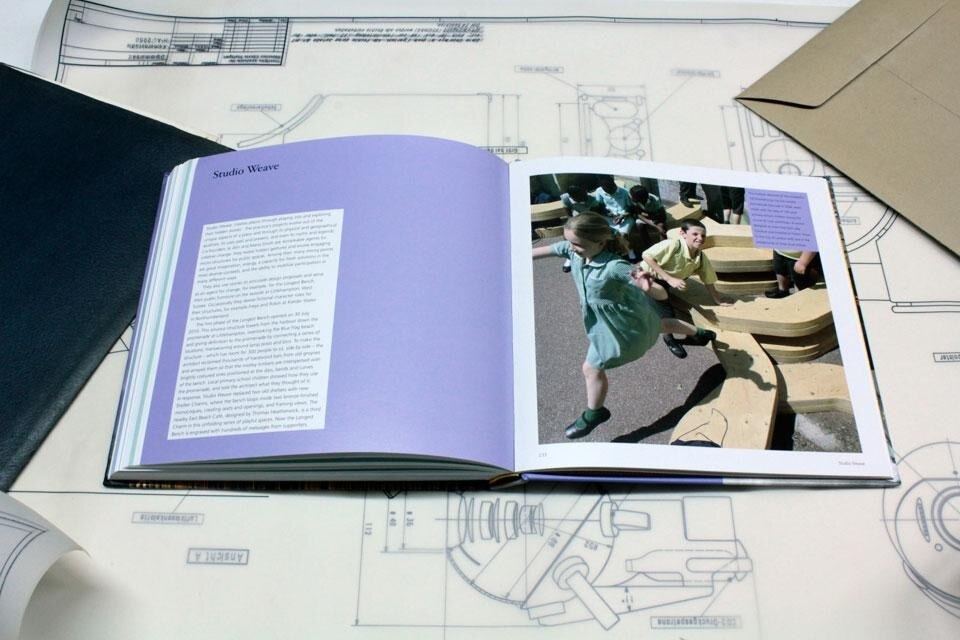

With climate change continuing, and the west's financial system under threat, young UK architects are again embracing a concern for the environment and a belief in the importance of civic values and public interaction, but they are also employing a bewildering array of new strategies to achieve their goals. "Pop-up" restaurants, moveable structures with varied programmes, and other buildings that defy categorisation are beginning to change the architectural language. It seems that the radical ideas formulated in the UK's world-renowned architecture schools are finally coming to fruition in the real world; it is no coincidence that some of the architects featured in the book have taught in those very schools. Even the UK's notoriously conservative local authority planning departments are catching the new mood by taking a more progressive approach to development on the green belt.

As Bullivant explained to me, "Today's younger practices are working in ways that are flexible and jumping the system now in a period of crisis. Responses to this crisis, as opposed to the last recession and its aftermath of improved conditions, bear signs of an even bigger deployment of means to create solutions cheaply, faster and in a more sustainable way."

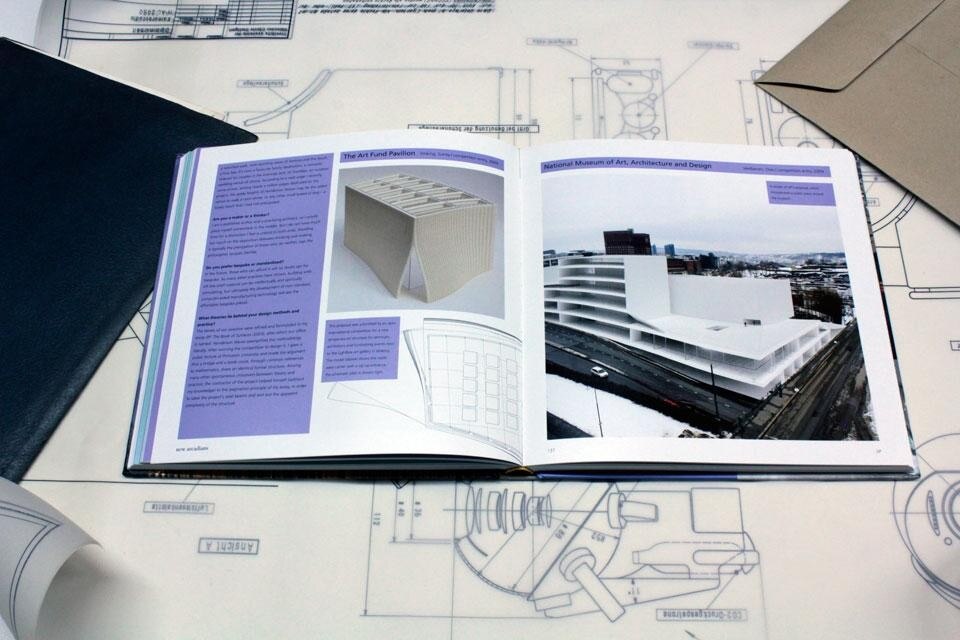

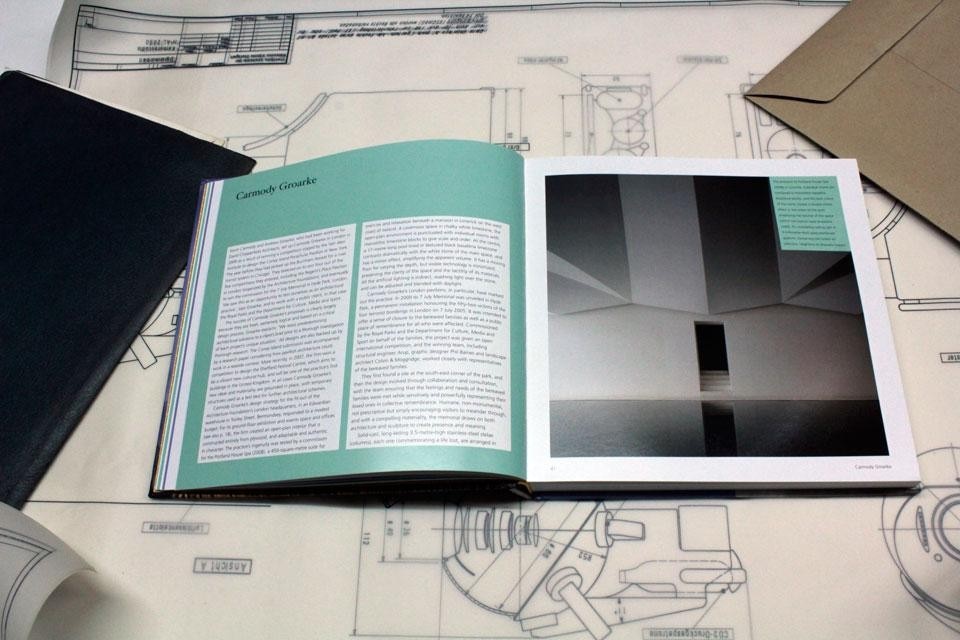

Often a writer's claims for an architect prove unwarranted when you see pictures of the work. That is not the case with Bullivant: firms such as IJP and Plasma Studio prove that the UK is at the cutting edge of architectural practice. The best images bring out the multifaceted nature of a design: for example, the section drawing of David Kohn Architects' A Room for London, perched on the roof of the Queen Elizabeth concert hall in London; AOC's elevation of its all-star hotel and rooftop park in the seaside town of Weston-super-Mare; and the perspective of Gort Scott's viewing platforms in the Lea Valley. I would have liked the book to include more such drawings; perhaps we have to wait for the first monographs to appear. Although the New Arcadians have received plenty of attention in the specialist and even national press, none of them has yet built a very large project, or been the subject of a big show.

It is not all passionate advocacy: in her introduction, Bullivant shines a discerning light on restrictive planning laws, the bland use of brick, narrow-minded eco-activists and the identikit cappuccino street culture, to name just a few examples