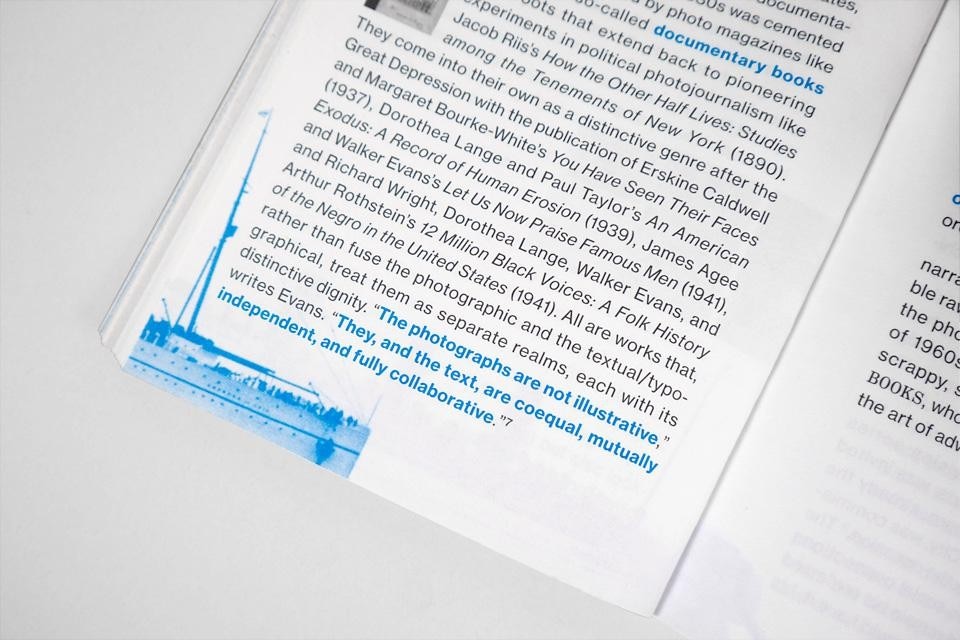

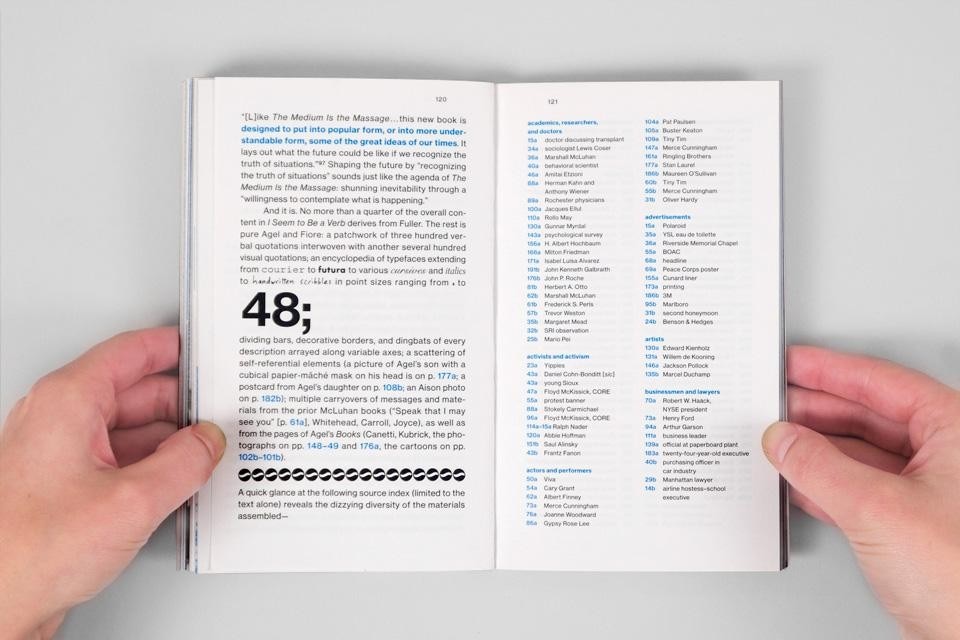

During the intense cultural ferment of the 1960s, a savvy and theatrical advertising guru named Jerome Agel combined previously disparate conventions and practices to transform one of the most populist publishing models of the modern era—the mass-market paperback. It was in this pulpy, constrained format that some of the most visionary thinkers of the time—Marshall McLuhan, Buckminster Fuller, Carl Sagan—found enthusiastic audiences whose emerging literacy in media and technologies was obviously affecting nearly every aspect of their lives. In addition, these books (notably McLuhan's The Medium is the Massage and War and Peace in the Global Village, and Fuller's I seem to be a Verb) dynamically combined type, photography, and design to create a new kind of (print-based) multimedia experience that both performed and described the hypersensory realities of the age.

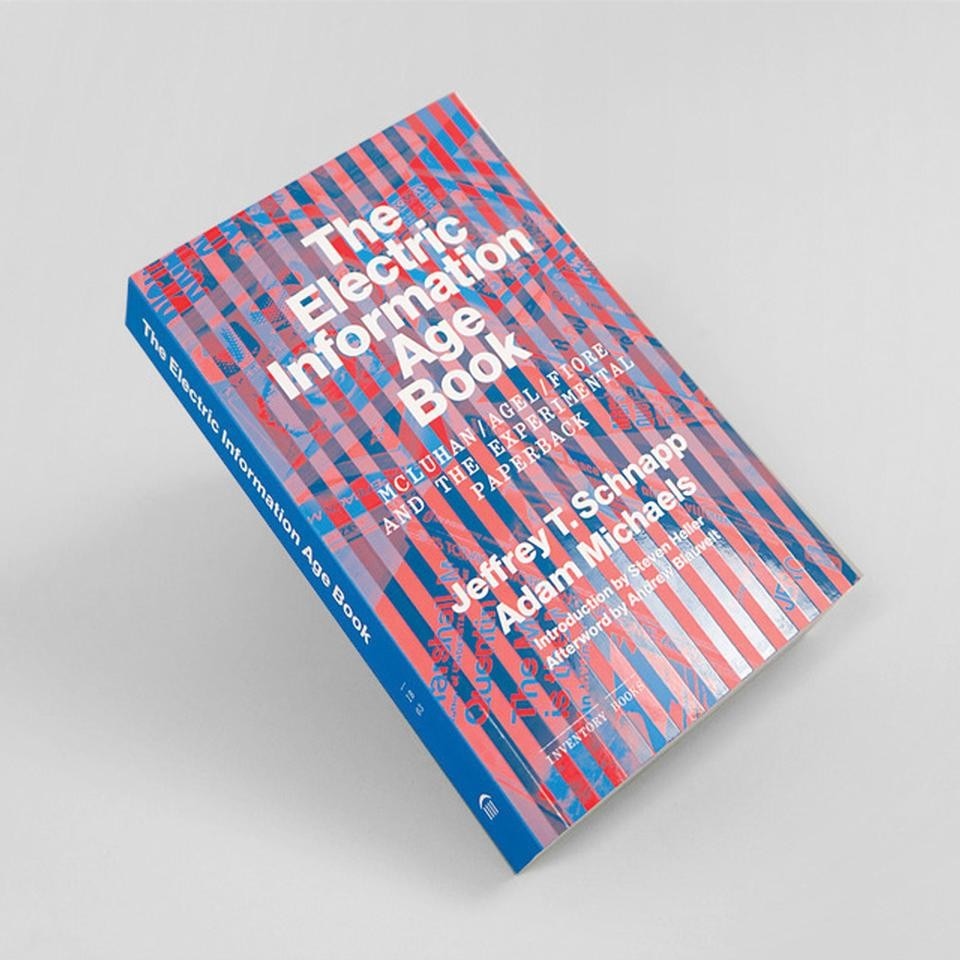

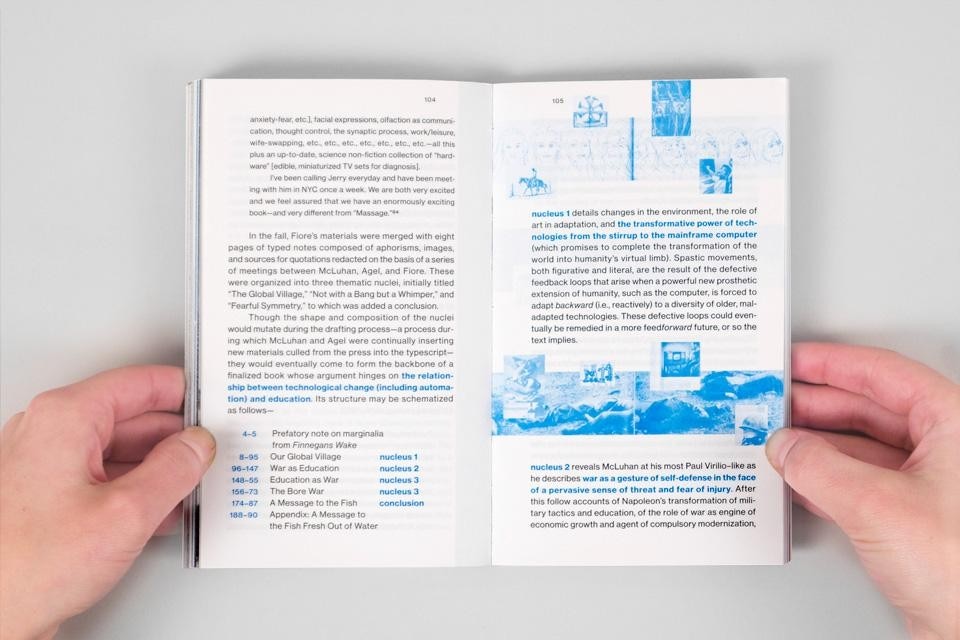

In the recent The Electric Information Age Book, media scholar Jeffrey Schnapp and designer/editor Adam Michaels (whose Inventory Books imprint are all in the same mass-market paperback format) revisit this relatively brief moment in publishing history (and the history of ideas), whose implications for the future of books still resound today.

Jeffrey Schnapp: Of the two, Agel played the larger role with respect to the publishing industry, with Fiore playing the shaping role with respect to the graphic texture and composition of their collaborative book projects.

Though a journalist by training, Agel was an industry insider whose deepest ties were to the advertising culture of Madison Avenue, which he preferred to the starchy gentility of the upscale book trade. His revolt comes out into the open with the foundation in 1964 of a scrappy newsprint monthly entitled Books, The Monthly Misnomer. Promoted as "our advertising agency" by Agel Publishing (which was, indeed, an advertising agency), it sought to wed the New Yorker with Book World, but within a madcap, eclectic, cartoony mold designed to deliver the unpredictable in every issue. This experimental subscription-only venue served as the incubator and launch pad for the collaborations with Fiore. What it lacked in polish, it made up in exuberance. Fiore introduced the polish into the book projects.

Like Books itself (which ceased publishing in 1968), the conceptual genre of books that Agel and Fiore devised would ultimately fail by the mid-1970s. But together they inaugurated a fresh and irreverent televisual cut-and-paste style of communication that was influential during its era.

Its contemporary legacies are as rife in the field of advertising as in internet culture, especially in those zones within the web where high- and low-brow forms occupy each others' ground.

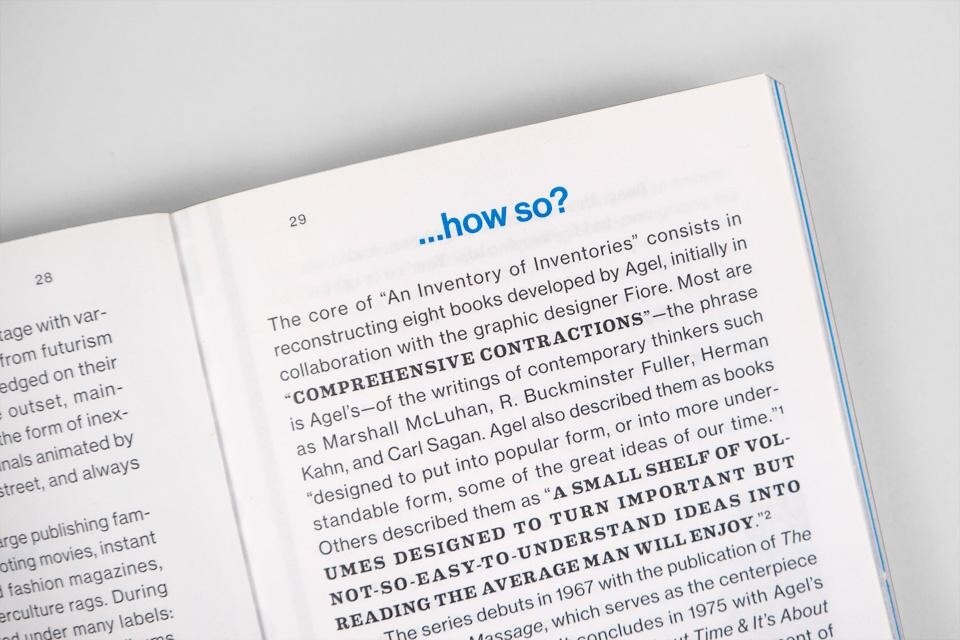

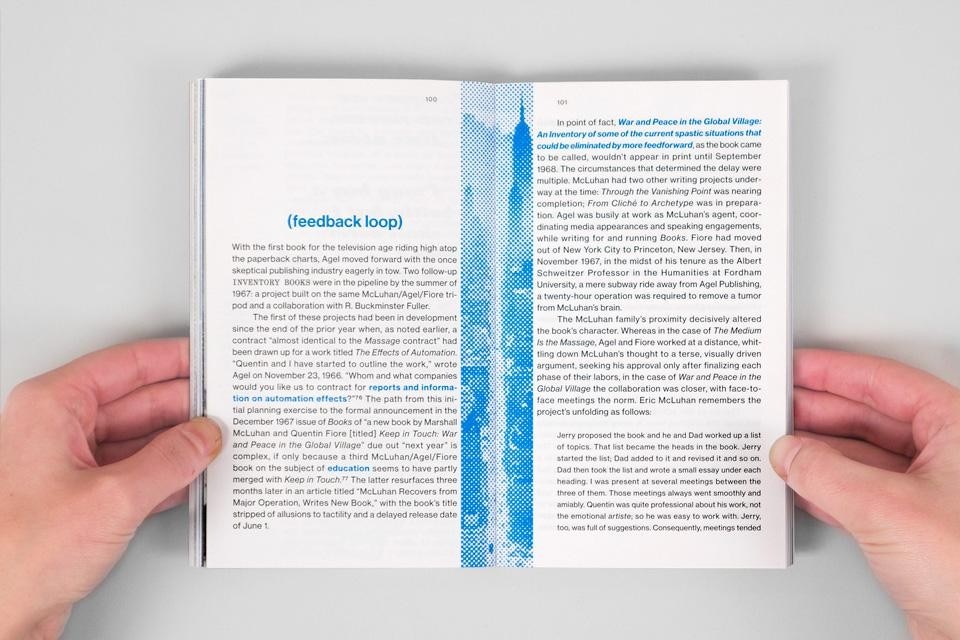

Part of the genesis of the Inventory Books series was the realization that work of this sort—in which images and text, and editorial and design processes, are closely intertwined—goes against dominant logics of how the publishing industry typically produces books. So the creation of the series was a way of establishing a situation in which these working methods could be productively explored, while retaining the goal of communicating to a wide audience, in this case through Princeton Architectural Press's existing distribution network.

It was in this pulpy, constrained format that some of the most visionary thinkers of the time—Marshall McLuhan, Buckminster Fuller, Carl Sagan—found enthusiastic audiences whose emerging literacy in media and technologies was obviously affecting nearly every aspect of their lives

AM: As Richard Kostelanetz interjected from the audience at a recent book talk that I gave on the EIAB, it's important to mention that The Medium is the Massage was also published in a larger hardcover format, in addition to the mass-market paperback.

Richard thinks the hardcover is the superior, more serious edition (he also wrote as much in a then-contemporary review). However, I've always been far more drawn to the paperback, primarily for its accessibility: a considerably lower price (both at the time of release, as well as for used copies), and easier portability—and thus greater potential for usage. I also love the complete surprise of opening up a cheap paperback and finding something as thoroughly unexpected as the textual and visual complexity found in Massage.

JS: Agel was very much engaged with the work of Toffler and cites him frequently. Both worked in and around the Random House circle. But Toffler was a skilled journalist who was more than able to handle his own mass media packaging. Wiener was also known to Agel, omnivorous as he was in his reading interests. As you note, the technical character of much of his work on cybernetics may have made him a less promising candidate but the principal reason was doubtless that Wiener passed away a couple of years before The Medium is the Massage hit the best seller charts.

Agel's authors form a relatively cohesive set. All either traffic in aphorisms and slogans or their work is readily translatable into short forms. A susceptibility to puns or word twisting of the shameless kind is pretty much a given, with McLuhan leading the pack. And among all there's a shared conviction that it's crucial that high-level thinking break out of its disciplinary molds and spill out onto the television screen and streets.

Agel was so committed to mass-market translations of this sort that when Elias Canetti's Crowds and Power found its way onto his desk, he immediately wrote to propose his usual media massage. (I've been unable to locate a response and suspect that there was none. Imagine the brooding, brilliant, introverted Canetti playing Marshall the Media Clown in The Jerry Agel Circus!)

AM: The mass-market paperback format has appealed to me since I was a kid, when I had a voracious reading appetite and nearly no money—I fondly recall reading everything from Stephen King to Friedrich Nietzsche in this format. For me, the appeal is simple and clear: the mass-market paperback is the least expensive and most portable of any standard book format. While the publishing industry tends to treat the mass-market paperback as obsolete, I hold the apparently anachronistic view that it remains the ideal format for serious reading. I might suggest that the ascent of the Kindle and similar devices is related to the publishing industry's neglect of the format; e-book hardware and software offer the portability and reduced prices that readers miss from their old paperbacks, albeit without the sensual qualities and specificity found in engagement with actual, individual objects (even if mass-produced ones).

AM: On page 188, a 1973 letter from Agel to McLuhan is quoted, in which the former proposes a new book building upon the success of Massage; Agel writes: "Quentin will not be involved in this production. I will be the sole responsible design, production, and contract party, per my recent successes." It appears that Agel felt an increased sense of confidence following books such as Herman Kahnsciousness. Also, Agel and Fiore each had a substantial amount of other work happening at the same as their collaborations, so the separation may not have been so dramatic.

The separation, in turn, accentuated temperamental differences. Agel continued along the same path massaging the media of the Mass Age. Fiore gradually returned to his abiding passion for traditional forms of craft, from bookmaking to artisanal paper production to the conventional luxury editions with which he concluded his career.

AM: While there is a good deal of pleasure to be found in both Agel and Fiore's separate works, their books together are stronger, and certainly more deliberate in appearance, than those created apart. While this is due to a wide range of factors (for example, the distinct advantage of working with McLuhan's words over Herman Kahn's), it does suggest that there are greater advantages to be found in collaboration than solitary work—especially in the case of Agel and Fiore, in which a skilled editor/producer, with an ear for a catchy phrase, and a sophisticated visual practitioner combined their talents to create something that they wouldn't have been able to achieve on their own.