Le Corbusier wrote this in 1923 in his historic Vers une Architecture. Almost a century later, if we replace the word "machine civilization" with "digital civilization" we might say that architecture finds itself in a similar situation. In fact, there is no doubt that we are at the beginning of very deep change—at least to hear Antoine Picon in his latest essay, Digital Culture in Architecture. Picon writes:

Confronted with a series of [contemporary] technological innovations, the only certitude we have is that the change they are bringing is profound. It might prove as radical and enduring as the transformation that gave birth to the architectural discipline at the beginning of the Renaissance.

What are these momentous changes?

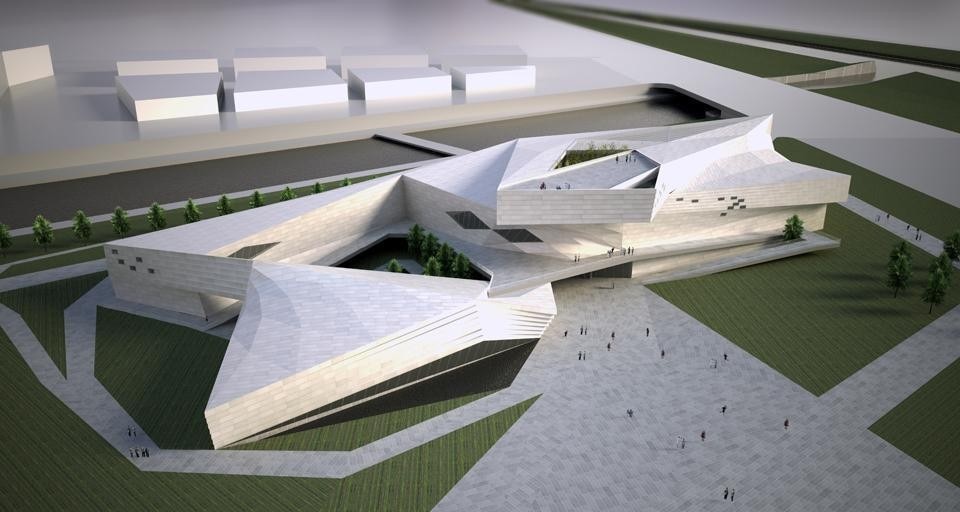

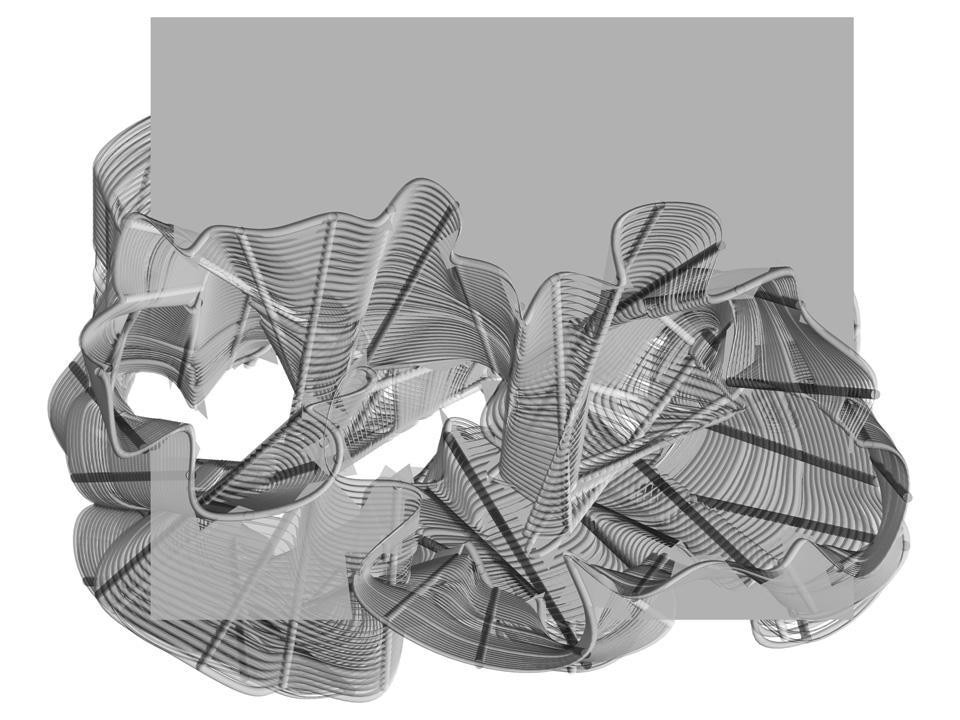

Common wisdom has it that impact of the computer and today's widespread use of digital technologies in the practice of architecture has created, above all, new formal languages. And it is doctrine that the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, designed by Frank O. Gehry in the 1990s, could not have been possible without the extensive use of the new three-dimensional modeling software and "digital assembly line" which allows the transformation of a three-dimensional model of an architectural component into its realization through numerically controlled machines; just as it would not have been possible to achieve the great formal variety that has characterized the leading architectural experiments of the last decade—by Frank O. Gehry, Zaha Hadid, UN Studio, among others—denominated in various ways: from Herbert Muschamp's "Digital Baroque"(1) to Greg Lynn's BLOBs (Binary Large Objects)(2).

"Blobs", folded surfaces, topological singularities have flourished, often giving the impression that architecture was entering a new baroque condition. But this morphological complexity is not the only dimension to be taken into consideration.

And in an uncharacteristically argumentative vein, he states:

In some cases, what seems left to architects is a task akin to fashion design, a perspective evoked a few years ago by Ben van Berkel and Caroline Bos with an enthusiasm that one is not obliged to share.

What, then, are the consequences of the digital revolution in architecture? Here Picon jolts the architecturally trained reader, who, for a moment, might think he or she is reading the wrong book. He rears up, in fact, with a long historical exegesis going back to the ostensible origins of digital civilization to first define when this phenomenon began:

[Historians] generally agree on the fact that digital culture has been made possible by the emergence of an information-based society at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a major transformation that corresponds roughly to what specialists of technology often call the Second Industrial Revolution.

Starting from the most interesting twentieth-century experiences, he identifies the potential for tomorrow's digital architecture

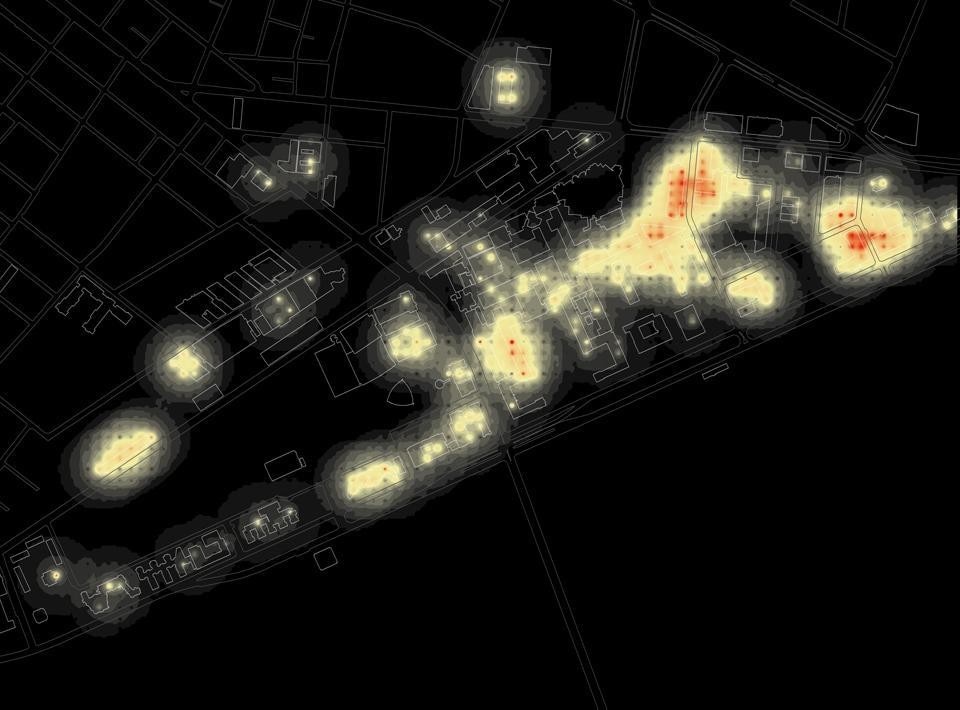

In connection with the rise of digital culture, [the architects'] main contribution may very well lie in the domain of augmented reality, that is, dealing with the interface between the physical and the virtual, rather than focusing almost exclusively on the latter.

Indeed this is the strength of Picon's book: starting from the most interesting twentieth-century experiences, he identifies the potential for tomorrow's digital architecture.

Aldo Van Eyck said that there is something similar in the concept of time held by both antiquarians and by technocrats—the first are sentimental towards the past, the second towards the future(3). Antoine Picon, in his dual role as historian and technocrat trained in the French Grands Écoles, surprisingly manages to combine both: to get excited about the past and about the future, composing one of the most complete and fascinating pictures of the architecture to come.

(1) The definition "Digital Baroque" was coined by Herbert Muschamp, New York Times architecture critic, in "When Ideas Took Shape and Soared", in: The New York Times, Friday, May 26, section B, p. 32.

(2) Greg Lynn, Folds, Bodies & Blobs: Collected Essays, Bruxelles, 1998.

(3) Carlo Ratti, Chandigarh Fifty Years Later, Domus, 814 Aprile 1999.