Between Earth and Heaven. The architecture of John Lautner

Edited by Nicholas Olsberg Rizzoli International, New Yor k 2008 (pp. 234, $ 60.00)

Some buildings outperform their own designers. They become part of the collective cultural humus, diffused via popular media systems that lack the filters of academic status or committed criticism. This may simply be because they form the backdrop to a successful film or a music star’s video, or because a top fashion house did their latest photo shoot there. Some buildings are a bit like those songs whose chorus everyone knows, but no one can ever remember the name or face of the singer. John Lautner’s buildings are a bit like this and perhaps it is no accident.

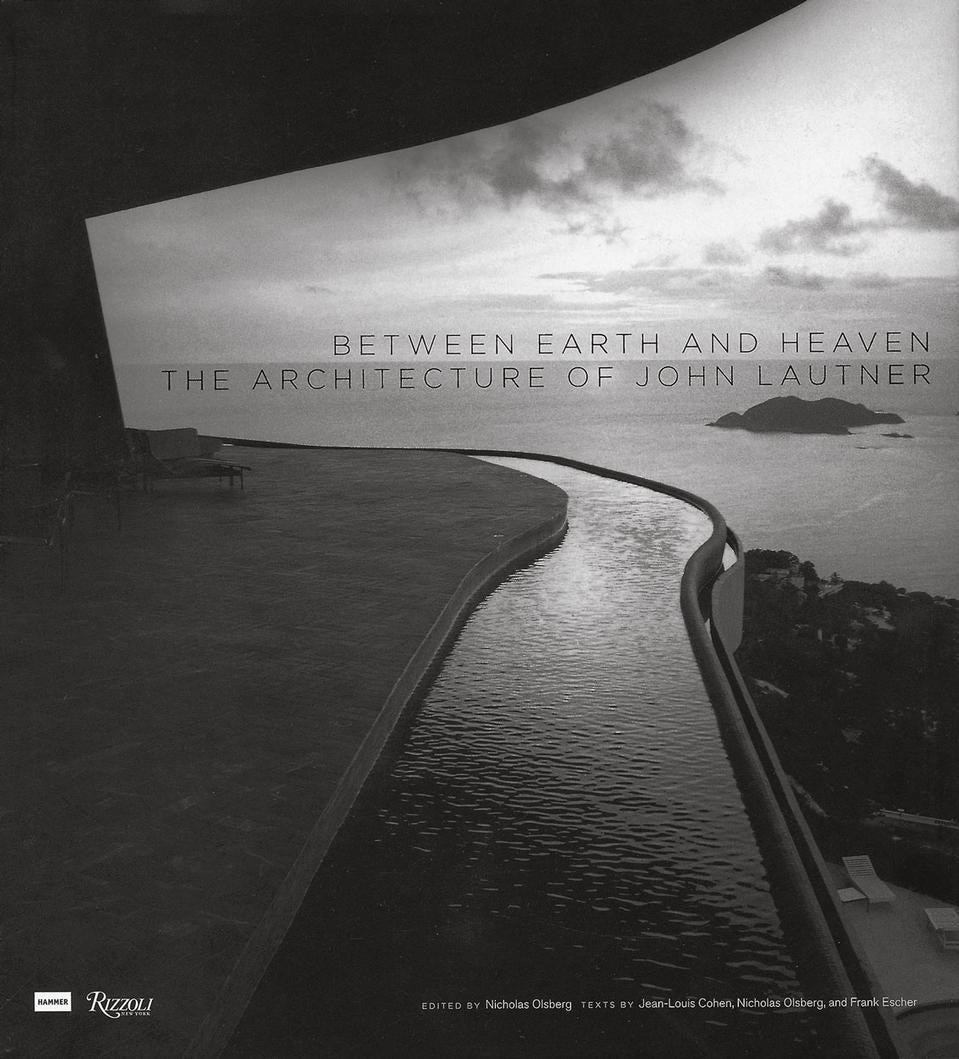

Lautner spoke of architecture in terms of structural invention, in which the components of the structure converge to develop the space. Its inhabitants are mere shadows, to be left blurred in the background, perhaps that of Acapulco – surrounded by the unbroken lines that fuse together the sky, sea and terrace of the Mar Brisas Residence, built in 1973. Lautner was always in search of the spectacular and, indeed, a certain thread can be discerned between his and Gehry’s most recent works.

It is therefore no surprise that his buildings, such as the Chemosphere, could rapidly mutate from dream to nightmare, albeit a whimsical one. However, the extremism of a house designed to resemble a UFO, hovering in midair above a single central mushroom-like pillar, is proof that, in organic architecture, Wright’s essence is not to be found in the forms but in the spirit behind them. Zevi stated this on observing the architecture of Lautner, who was a former pupil of Frank Lloyd Wright and an interpreter in his own right of organic design. The substance may lie elsewhere, far removed from the snapshots of these spectacular buildings that were so loved by Hollywood film stars and that still today are perfect and favourite locations for film and musical productions.

Between Earth and Heaven, a monograph edited by Nicholas Olsberg, examines the boundaries between form and substance, design and intuition, artifice and nature in Lautner’s architecture. His ambiguity is clear in the involuntary confusion we feel when looking at the photographs of his built projects and mock-ups. The distinction between true and fake is not always clear when you have concrete walls that turn suddenly like pieces of cardboard, and wooden beams that stretch out like sticks of balsa wood. Even those living there sometimes look like cardboard cut-outs. The chapter entitled “Structuring Space” illustrates projects that show how organic unity does not stem from the form but rather from the normality with which even the most refined structural calculation or the most ingenious technological application yields to the brutal force of nature. In the Pearlman Mountain Cabin, for example, the tree-trunk columns are a forest within the forest and seem to have difficulty in holding up the projecting terrace; in the Walstrom House, the solids and voids are glass and wood, and the house seems to carve its spaces directly out of the shrubs and leaves that surround and penetrate it. It is no coincidence that Lautner’s designs are based on refined engineering invention; Hope House looks just like a shell poking out of the sand of Palm Springs, without revealing the nature of its structure.

Yet, in these snapshots – which are almost metaphysical, but then also geometric – you realise that the architecture’s spectacular effect is produced via human-scale dimensions. No sudden drops are needed to instil a sense of the monumental in a cantilever roof or pilework; the comparison with the landscape is manifested in the symbiotic relationship between design and nature, observed exclusively by the onlooker. In this sense, we can perhaps say that it is the inhabitant who is really behind the camera, the involuntary photographer of a film that permits no other presence

It almost signifies a privileged relationship between architecture, landscape and, finally, the inhabitant. It is unbelievable if not experienced personally, like a blurred shadow against the backdrop of the Acapulco seafront.