On social networks, there is a graveyard that almost no one talks about. Considering the decades-long history of the platforms we share much of our personal and professional lives on, it is not surprising that an increasing number of profiles belong to deceased people.

As one of the oldest, born in February 2004, it is also not surprising that Facebook is the social network most affected by this inevitable phenomenon. Today, there are already hundreds of millions of accounts belonging to deceased people, which could surpass the number of living users by 2070 – assuming Facebook still exists – and reach 4.9 billion people by 2100 (after all, almost all of the current 2.9 billion users will no longer be on Earth by the end of the century).

As morbid as it may seem, the aging of the generation that first participated in the social media era is a phenomenon full of practical consequences that, in most cases, we are not yet equipped to cope with. For instance, you may have received a notification reminding you of the birthday of someone who is no longer alive, while some have even received messages sent from deceased friends (of course, these were cases of identity theft).

On the other hand, Facebook is not automatically informed of the death of its users, meaning that these accounts remain visible and accessible, as well as appearing indefinitely on friends lists and in groups they were subscribed to. In order to cope with an increasingly pressing issue, the first solutions have emerged in recent years that allow users not to leave their personal accounts to their fate.

Today, there are already hundreds of millions of accounts belonging to deceased people, which could surpass the number of living users by 2070.

The first and most intuitive solution is to give the account password to a highly trusted person, who will then follow our instructions in the event of our death (for example, by deleting the profile). However, with the advent of two-factor authentication, this simple method may become almost impractical, as well as violating the platforms’ terms and conditions in some cases.

Facebook memorial accounts

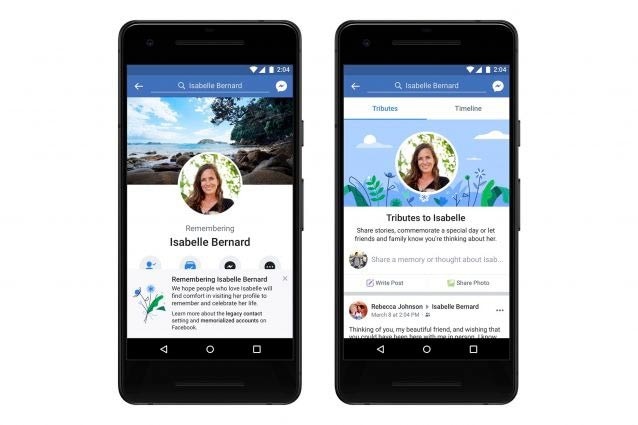

As a result, it is the social networks themselves that have begun to take control of the situation. In this regard, Facebook is undoubtedly the platform that has most actively sought solutions. First of all, Facebook stipulates that, upon being notified of a user’s death, the profile of the deceased will become a "memorialized" profile, and the word ‘Remembering’ will appear next to the person’s name.

In principle (there may be differences depending on privacy settings), people can write on memorial profiles and view existing posts and images, but these will no longer appear (understandably) among suggested friends or birthday notifications.

There is also the possibility of choosing a legacy contact who can write a pinned post (usually a commemorative one), update the profile picture, respond to new friend requests (perhaps from a relative who was not previously added as a friend), and other similar actions. Most importantly, the legacy contact can decide whether they want the profile to remain on Facebook or be deleted entirely (according to a survey, 50% of users want their Facebook profile deleted after their death, 25% want it left as is, and another 25% want it transformed into a digital memorial).

The value of a digital profile

However, not all social networks are as equipped as Facebook. For example, Twitter (later rebranded as X) has decided to delete long-inactive accounts. This has raised a lot of protests as it has prevented friends and followers from continuing to visit them and see the memories stored within them.

For instance, you may have received a notification reminding you of the birthday of someone who is no longer alive.

Not only that: since almost all of our correspondence and interactions are via digital means today, thoughtlessly deleting an inactive account is the digital equivalent of throwing away a box of photos stored in the family attic. Even worse, the risk in some cases is erasing the modern-day equivalent of the correspondence between Einstein and Freud on war or between Goethe and Schiller (all private exchanges that were not intended for publication). Who can rule out the possibility that within an as-yet-unknown Instagram profile there might be a treasure equivalent to the trunk of photographs of Vivian Maier?

The limitation of this parallelism is that today’s messages, writings, and photos are no longer stored in the attic of the grandparents’ house, but in the servers within colossal data centers owned by companies like Meta, Google, Amazon, etc. In short, storing our data not only takes up space but costs money. Unless there is an economic incentive, it is inevitable that, sooner or later, some of this material will be deleted (a decision already made, for instance, by Flickr and others).

The digital afterlife industry

So, how can we preserve our content for posterity? First of all, it is already possible today to download all data from Facebook and save it for our children and grandchildren (preferably on a hard drive, as storing it in the cloud would pose the same exact issues). To help people navigate the various difficulties they may encounter along the way, a new flourishing sector, dubbed the ‘digital afterlife industry,’ has emerged for some time now.

It is a fledgling market with limited data (some estimate the business to be worth around $350 million), including startups like the American GoodTrust and the Japanese Hanamaru Syukatsu. These companies help people choose who to entrust their accounts to, decide how to transform or delete them, where to archive the material, and most importantly, how to handle the bureaucratic complexities involved.

In short, storing our data not only takes up space but costs money.

As Rikard Steiber, founder of GoodTrust, has explained to Rest of World, managing the digital afterlife ‘presents a series of unique challenges that tend to be contingent on where the person lived. In the U.S., for instance, when a person dies, it is necessary to get a court order to access an online account. And that’s just one account. If you want content from multiple sources, you need to have multiple court orders in multiple formats.’

Among the 57 startups active in the field, there are also some that do not focus on managing our social media but on creating interactive digital memories. For example, HereAfter periodically sends messages read in the voice of the deceased person, while StoryFile allows you to ask questions to a deceased friend or relative, automatically selecting the most suitable response from those recorded while they were still alive.

The most ambitious of these ventures is MyWishes, which allows users to freely specify within a personal profile how they want their social media to be managed, indicate which songs should be played at their funeral, the achieved – or missed – milestones of their lives, and, most importantly, leave a final message for their loved ones.

When MyWishes receives information that one of its users has passed away, all the wishes indicated become accessible to anyone searching for the user’s name on the platform. Indeed, the profiles are not reserved for trusted contacts but are public. This, after all, seemed inevitable: we started by discussing the abundance of deceased accounts on Facebook and concluded by describing what appears to be a new social frontier: digital graveyards.