Quant was among the key figures of a libertine, yet never vulgar England. That of the Swinging London which, since the mid-1960s, keeps on to inspire and ignite music, fashion, costume and the whole of design.

Born to a family of teachers, Quant studied art at Goldsmiths, where she met her future husband Alexander Plunket Greene: as broke as he was stylish, histrionic and fundamental to the designer's career.

When in 1955, at the age of 21, he inherited a sum of £5,000, the couple's fortunes changed fortnightly with the decision to take out a mortgage for a property in Chelsea: in the basement he opened Alexander's Restaurant, on the ground floor Bazaar, Mary's first boutique.

Before that, though, Quant went through training at Erik's in Mayfair. Money was tight and the future fashion designer lived on a diet of one chocolate biscuit a day. As Cecil Beaton hyperbolically noted: “There were weeks when only an aspirin touched Mary’s lips and, but for the Jamaicans in nearby Claridge’s kitchens handing over their refuse bins, she would have starved.”

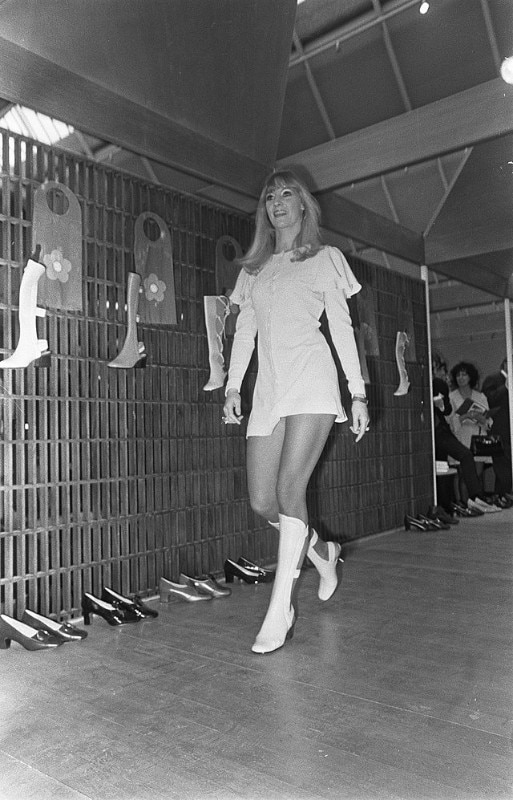

The 1960s would pay her efforts back, consigning Quant to international fame thanks to her most significant garment: the miniskirt. The design thrilled and shook the West, where everything became 'mini': from cars (Quant herself drove a black Mini with a black leather seats) to songs, such as that 'Mini Mini' with which Jacques Dutronc became a pop idol in Paris. In the designer's creations there was a desire to update the lexicon of women's fashion, breaking with the couturier tradition that Dior's New Look had imposed in the second half of the 1940s. Quant's silhouettes and patterns spoke to an entire generation, the one that had endured the post-war austerity and that reclaimed their right to fun.

The miniskirt, in fact, more than an invention was an intuition, which is what is required of great designers and statesmen. The ability, that is, to interpret the needs of the population. Quant intercepted the buzz in the London air and turned it into legend. As designer Nanda Vigo recalled in her biography ‘Giovani e Rivoluzionari', she wore the miniskirt on the French Riviera as early as the 1940s and 1950s, in a spirit of liberation of the body which followed the oppression brought on by the Second World War.

After all, Quant had already opened Bazaar, his own boutique, in the mid-fifties, merging her research on slim and essential silhouettes with American sportswear and the Beatnik and Pop culture that was permeating the London Art Colleges of the time, the true avant-garde of the Swinging London that was soon to follow. A Chelsea girl long before Nico and Twiggy.

Quant herself said that she grew up “not wanting to grow up, growing up seemed so terrible, children were free and sane.”

This attitude explains how it was the zeitgeist that had to catch up with the designer and not, as it is usually the case, vice versa.

In the wake of the philosophy of democratisation of design that permeated post-war culture, the fashion designer was one of the first to market a line of products - from cosmetics to accessories - that would make the imagery she created accessible across social social classes.

They were defined by a powerful yet essential coordinated image: a black daisy on a white background, ta flawless synthesis of modernism and Op Art, as well as – one could note – a predecessor of flower power.

If the miniskirt represented a watershed, so did the image with which Quant presented herself to the public. A bob cut as essential as it was instantly recognisable: just like her creations.

If the miniskirt represented a watershed, so did the image with which Quant presented herself to the public. A bob cut as essential as it was instantly recognisable: just like her creations.

The demiurge, hairdresser Vidal Sassoon, created a revolution within a revolution with a hairstyle that was as much a design object as it was harmonious in its sharp synthesis of volumes. It would end up, like the miniskirt, defining an entire generation: from model Peggy Moffitt – the face of Optical fashion and muse of many photographers – to actresses like Elsa Martinelli and singers like Caterina Caselli. Her bob, sculpted in Jill Vergottini's Milan salon, was in fact fundamental in decreeing her disruptive pop success in the Belpaese.

Many are the anecdotes about the impact the miniskirt had on the lives of young women. From schoolgirls who used to take the skirt length in by stitching an impromptu hem with safety pins to reveal their knees when leaving home or classes, to Italian socialite and fashion designer Marina Ripa di Meana, who was arrested for showing her thigh in public in front of a giant Lenin artwork from under a mini-dress when travelling in Russia with her companion, the artist Franco Angeli.

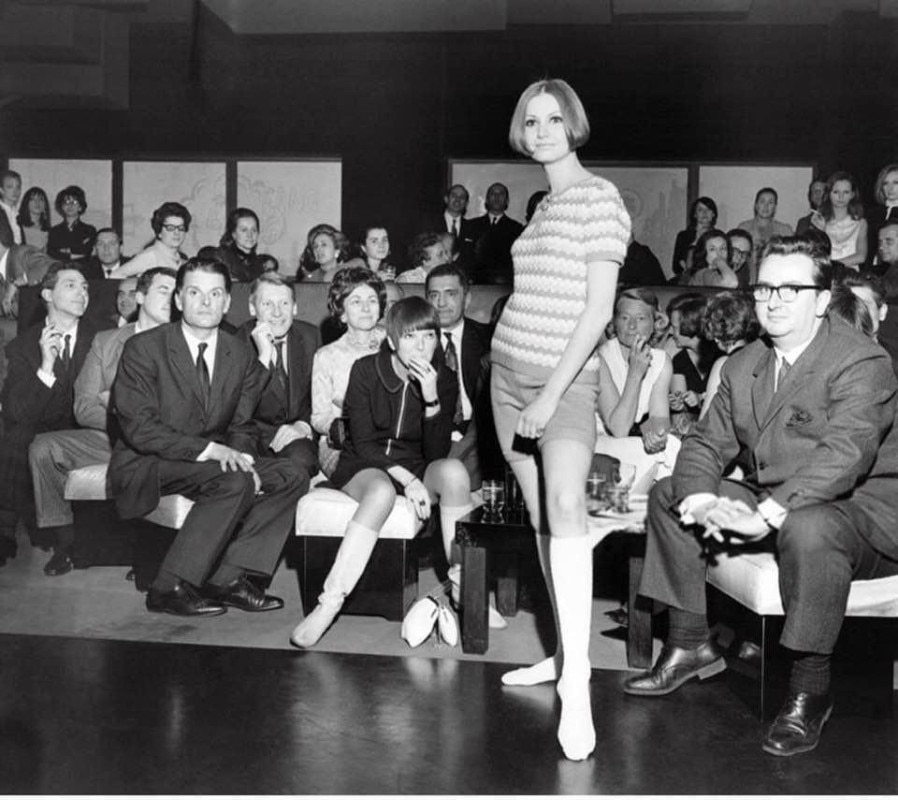

It was in 1967, at the height of Swinging London, that Quant's first fashion show took place in Milan, jointly with the presentation of her cosmetics line.

Her Bazaar on Kings Road closed its doors as early as 1969, after international success, making way, not many blocks away, for another incipient costume revolution: that of Vivienne Westwood.

By this time Quant was already crystallised in British pop culture. The first retrospective dedicated to her dates back to 1973, followed by one at V&A in 2019, whereas her OBE dates even back, to 1966. Quant was later made Dame in 2015 and Companion of Honour just a few months ago.

Opening image: Mary Quant fashion show, Milan, 1967. Courtesy Archivio Ragazzi di Strada