Fabrizio Pesoli : Let us start from the beginning. When did you decide or realise you would become an artist?

Francisco Brennand:It is hard to pinpoint your first contact with the ambiguous world of painting, and art in general. It is like asking a saint on what day they noticed their saintliness. As if saints could perceive their beatitude without somehow immediately losing all of it. Certainly, there must be influences that drive a young person to take an interest in what we call art but, for every artist, the inspiration does not originate in nature and all its impenetrable facets but in other artists — sometimes predecessors and sometimes others, much farther back in time. I see no interruption in this eternal chain of inspired people, from cave drawing to Michelangelo and on to the present day. They must, however, go through the essential and incontrovertible apprenticeship because art is primarily an officio, a craft. That is why we have the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence. In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, apprentices and their masters formed a perfect community. Everything produced in the artistic sphere in those days was based on the excellence of their craft.

We had collections of pictures and Oriental porcelain in the family home. My father was extremely erudite, in literature and music in particular. He played the piano and spent two years in Germany studying it; however, he inherited a sugar plant and ended up neglecting his vocation, which I believe then fell onto me, marking my destiny.

I was not precocious at drawing but produced caricatures of my least favourite professors, especially the Marist Fathers. I started reading about painting when I was very young, and was captivated by the trinity that forms the basis of modern art: Cézanne, Van Gogh and Gauguin. Before them, I was fascinated by Gustave Doré's engravings for the Bible and Don Quixote... In February 1949, I went to Europe for the first time, to Paris, and I already knew who my favourite artists were, and those I absolutely had to see and study.

My 1952 trip to Italy confirmed my admiration for Leonardo, Masaccio, Piero della Francesca and Donatello. I wrote a sort of "Italian diary", just a few pages to remind me of my stays in Genoa, Naples, Rome, Perugia, Deruta, Arezzo, Borgo San Sepolcro and Florence. I didn't visit Venice until 1990, for the Biennale, and I do not have to tell you the impact it made on me. I had long been an admirer of Vittore Carpaccio.

When I returned to Brazil, I had already come across the ceramics made by Picasso in Vallauris, in southern France, Joan Mirò's amazing experiments and the chapel in Saint-Paul-de-Vence. My contact with Italian majolica was equally important but, even more than this, I believe I was influenced by the unique atmosphere in certain Umbrian towns, with their small civic museums and fields of olive trees stretching as far as the eye can see.

You have met and admire artists such as Picasso, Brancusi and Balthus. Yet, you do not consider yourself "related" to any 20th-century avant-garde.

No modern artist — in the Western world, at least — can say he hasn't been influenced by the School of Paris. This certainly includes me, and this influence continues to work in my favour rather than against me. Clearly, I am related to all of them, otherwise I would be an alien!

It is hard to pinpoint your first contact with the ambiguous world of painting, and art in general. It is like asking a saint on what day they noticed their saintliness

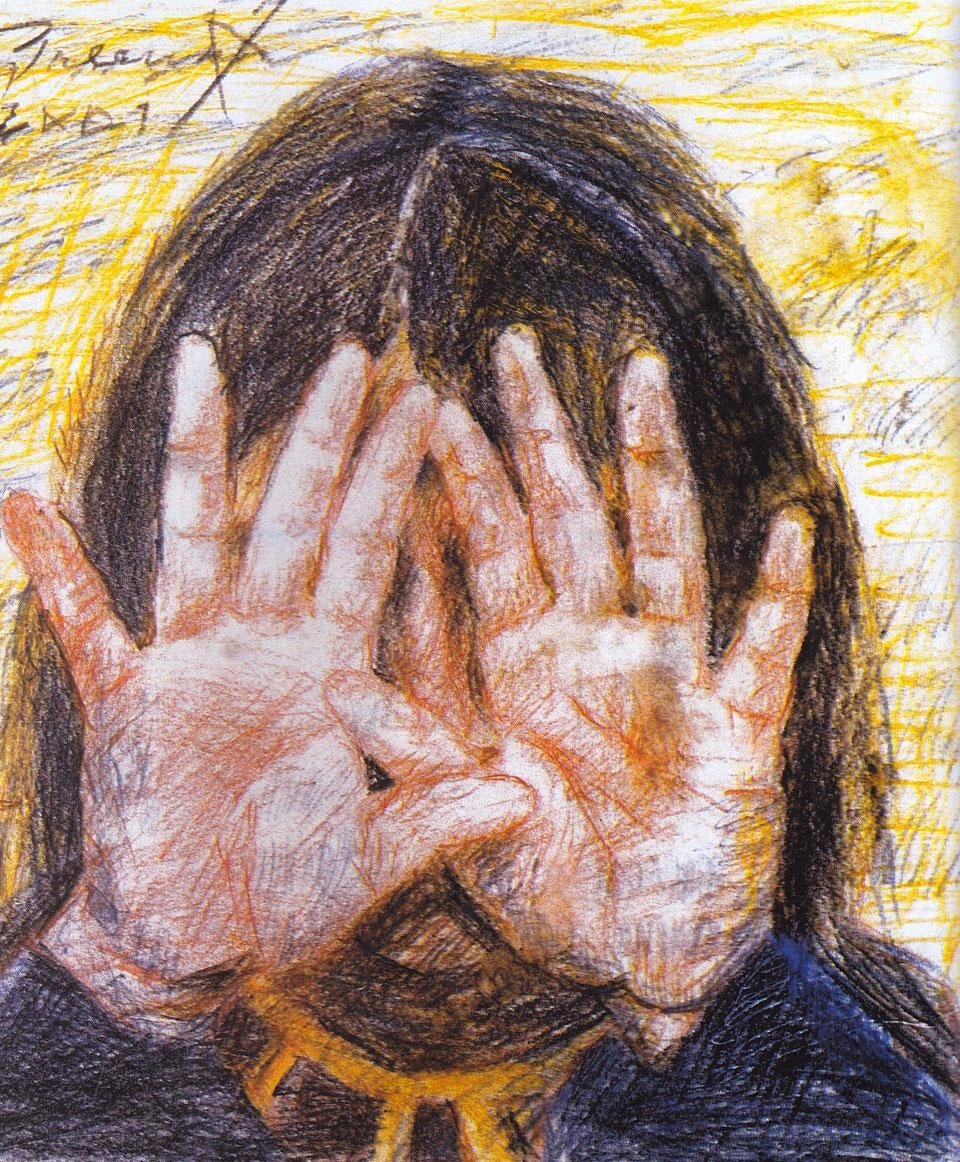

I am not a philosopher but a painter and sculptor. I do not claim to demonstrate anything, only to give myself to my craft and sometimes get it right. When I say things are eternal because they reproduce themselves and that eternity is reproduction, I want to remind people that we, too, are a part of the Universe which also reproduces itself. Whether modest or prudent, I am saying just one thing – we are looking at the Enigma.

Every apprenticeship is a form of slavery. I learnt to paint in Europe, in the broadest sense of the word, and so far I have failed to escape from its rigour. If I say that I have no mother country when I make ceramics, it is simply because when I work with earth and clay I tend to coexist with the primeval elements. "The future has an ancient heart", as Italy's Carlo Levi says. I do not see a more profound relationship with the artistic tradition of my country in my work, which in itself is closely bound to Europe. The Paulista Oswald de Andrade's "cannibalism" was more pose than artistic manifesto. San Paulo's Modern Art Week lasted three days and, more than anything else, was an attempt to reconnect with the old lost thread, which you Europeans already exhausted long ago: Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, Expressionism, Surrealism, Suprematism... All the "isms" had been used up by 1922, but it was a necessary event because things started to evolve from then on in Brazil.

The 18th-century Brazilian sculptor Aleijadinho is, perhaps, our only genius. I am not a genius so I cannot compare myself to him. I will, however, agree with the blood and terror...

In your L'Oracolo, you speak of the artist as of a shaman, "he who senses the mystery". Do you still believe this? Today, the mystery seems to vanish and the direct experience ("eating clay", as you say) is giving way to increasingly mediated forms of knowledge...

Scholars say that the shamans or the initiated would have produced the cave drawings. I do not believe that, today, mystery would ever bestow its charisma on any artist who conforms to the system of contemporary reality. The post-moderns are the epitome of the fallen angel... eating clay might be a path to salvation but how can you?

After so many completed works, what is your next project?

I have none. I stand alone, just as the day I was born, before what all of us must one day do. Accept the inevitable.