By the beginning of the millennium, we were on the road to the dematerialisation of culture and communication, more or less halfway between the machinist and early-numerical utopia of the Centre Pompidou and our smart contemporary era attempting to move into the metaverse. The Cyber- prefix stil used to sound up-to-datel, personal computers and video media were replacing paper and the last survivors of analog technologies, escorting us from the 20th century to the much anticipated 2000s. Toyo Ito created an architecture extending this phenomenon to the everyday cultural activities of an average city, assuming at the same time the value of a symbolic project for a whole era, with global relevance both for culture in the broadest sense ("it is a media suit, an externalised brain" the designer says) and for the architectural realm itself, involving then-emerging or recently established figures such as Kazuyo Sejima, Karim Rashid and Ross Lovegrove. Domus would then share all stories and reflections on this milestone in March 2001, on issue 835, with an essay by Toyo Ito himself and words by Deyan Sudjic.

Tarzan in the media jungle

by Toyo Ito

The curtain has gone down on the age in which museums, libraries and theatres were still able proudly to celebrate their role as cultural landmarks, as individual architectural archetypes.

Paintings on the wall and books printed on paper no longer enjoy an absolute, privileged position. The electronic media have turned them into objects measured by their relative value, not by absolutes. Paintings, books and films will in future be counted alongside electronic media such as compact discs and video tapes, without any discriminating sense of hierarchy. People will use both types of media in a complementary manner. Enjoying paintings and books through electronic media will demolish the once established, archetypal, form of the museum and the library.

They will all be fused into a single, seamless architectural type, and there will be no boundaries between the museum, the art gallery, the library or the theatre. They will all be reconstructed in a new form, the Mediathèque, which will be like a convenience store for the media, in which all forms of media are arranged together. This new form of convenience store-like public building will not be a symbolic presence, marooned on the far side of an empty plaza away from the life of the city. Rather it should be located close to a railway station, open until midnight seven days a week, ready to serve the public in their daily life.

In the 1960s, Marshall McLuhan said “clothing and shelter are an extended form of our skin”. From ancient times, architecture has served as a means to adjust ourselves to the natural environment. It functions simultaneously as an extension of skin, in relation both to nature and to information. Architecture has to act as a media suit now. People, when clad in the mechanical suit that is called the car experienced an expansion of their physical body. People wearing a media suit can be described as having had the capacity of their brains expanded. Architecture in the guise of a media suit can be described as an externalised brain.

In the context of the whirlpool of an information overload that threatens to drown us all, individuals can freely browse through information, attempt to control the outside world, and address themselves to that world. Instead of addressing the outside world, protected by the armour of a hard, shell-like suit, people are now in a position to do it by wearing a light, pliant media suit which is the embodiment of the information vortex. People clad in such a media suit are the Tarzans of the media jungle.

The information vortex

by Deyan Sudjic

Sendai is a quiet and orderly provincial city, a three hour train journey north of Tokyo, far enough away to feel that you have really escaped from the endless tentacles of Japan’s all consuming megalopolis. Its a grid city and by Japanese standards is far removed from the chaos of Tokyo. The skies in November are crisp and blue. The streets are lined with trees. There are Christian churches in the city centre. It is reassuringly comfortable, and yet just a little dull.

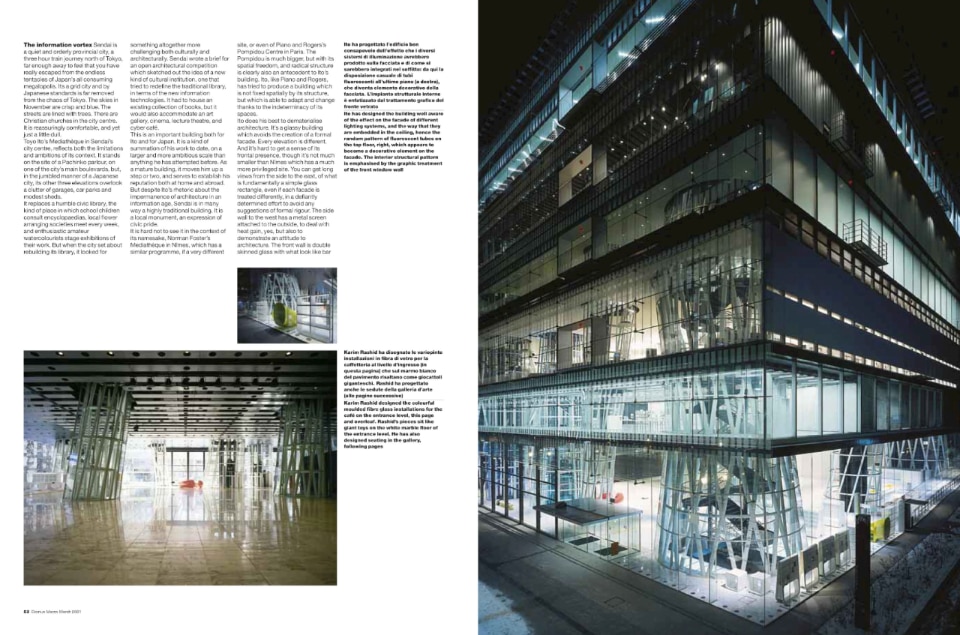

Toyo Ito’s Mediathèque in Sendai’s city centre, reflects both the limitations and ambitions of its context. It stands on the site of a Pachinko parlour, on one of the city’s main boulevards, but, in the jumbled manner of a Japanese city, its other three elevations overlook a clutter of garages, car parks and modest sheds. It replaces a humble civic library, the kind of place in which school children consult encyclopaedias, local flower arranging societies meet every week, and enthusiastic amateur watercolourists stage exhibitions of their work. But when the city set about rebuilding its library, it looked for something altogether more challenging both culturally and architecturally. Sendai wrote a brief for an open architectural competition which sketched out the idea of a new kind of cultural institution, one that tried to redefine the traditional library, in terms of the new information technologies. It had to house an existing collection of books, but it would also accommodate an art gallery, cinema, lecture theatre, and cyber café.

This is an important building both for Ito and for Japan. It is a kind of summation of his work to date, on a larger and more ambitious scale than anything he has attempted before. As a mature building, it moves him up a step or two, and serves to establish his reputation both at home and abroad. But despite Ito’s rhetoric about the impermanence of architecture in an information age, Sendai is in many way a highly traditional building. It is a local monument, an expression of civic pride.

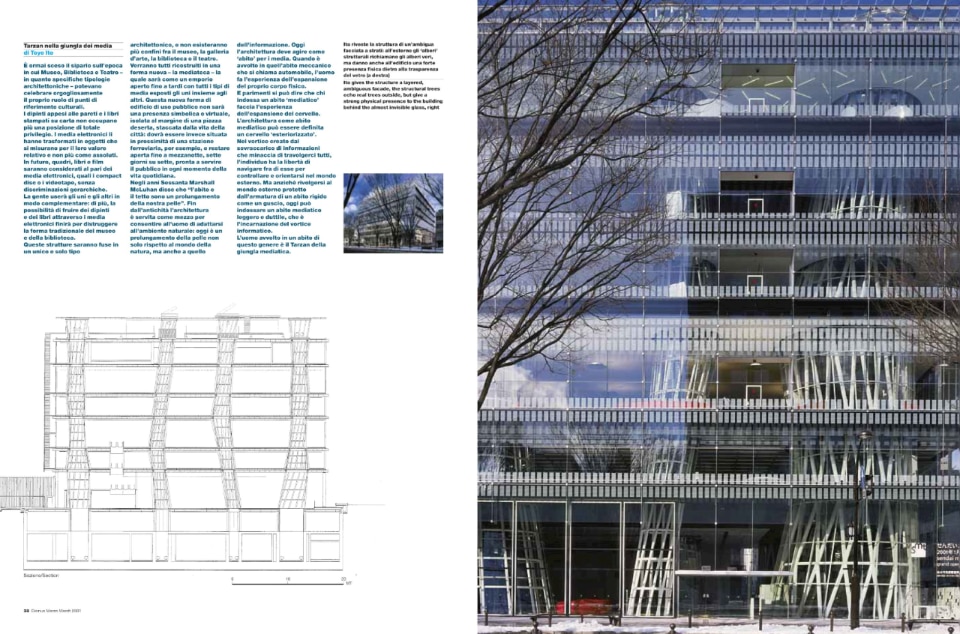

It is hard not to see it in the context of its namesake, Norman Foster’s Mediathèque in Nîmes, which has a similar programme, if a very different site, or even of Piano and Rogers’s Pompidou Centre in Paris. The Pompidou is much bigger, but with its spatial freedom, and radical structure is clearly also an antecedent to Ito’s building. Ito, like Piano and Rogers, has tried to produce a building which is not fixed spatially by its structure, but which is able to adapt and change thanks to the indeterminacy of its spaces.

Ito does his best to dematerialise architecture. It’s a glassy building which avoids the creation of a formal facade. Every elevation is different. And it’s hard to get a sense of its frontal presence, though it’s not much smaller than Nîmes which has a much more privileged site. You can get long views from the side to the east, of what is fundamentally a simple glass rectangle, even if each facade is treated differently, in a defiantly determined effort to avoid any suggestions of formal rigour. The side wall to the west has a metal screen attached to the outside, to deal with heat gain, yes, but also to demonstrate an attitude to architecture. The front wall is double skinned glass with what look like bar code marks tattooed on to them. They are basically decorative, though they probably have an impact on thermal performance, and certainly help to heighten the sense of ambiguity of the facade. There is a moire pattern as you look out from the inside.

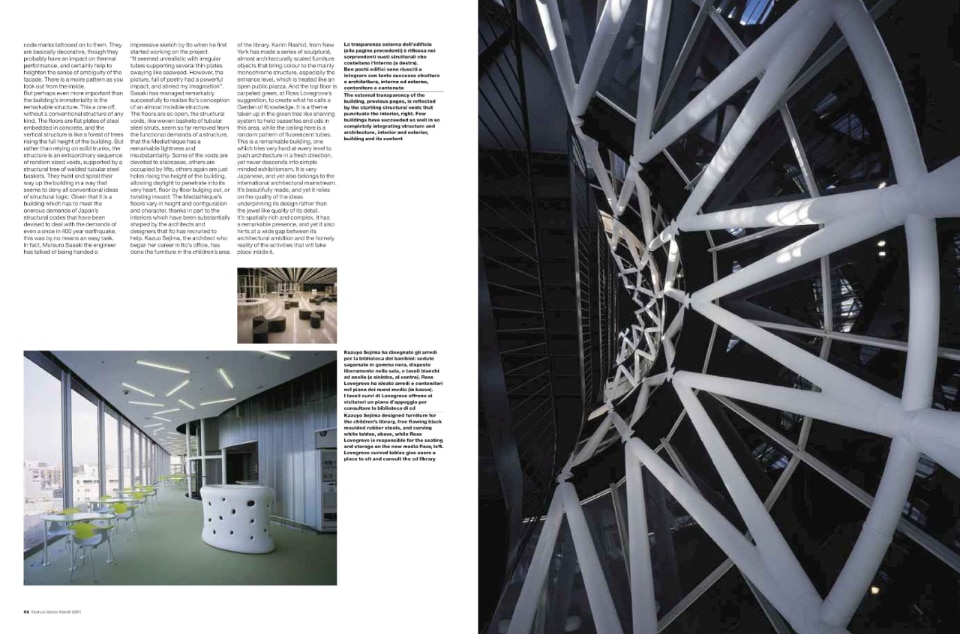

But perhaps even more important than the building’s immateriality is the remarkable structure. This a one off, without a conventional structure of any kind. The floors are flat plates of steel embedded in concrete, and the vertical structure is like a forest of trees rising the full height of the building. But rather than relying on solid trunks, the structure is an extraordinary sequence of random sized voids, supported by a structural tree of welded tubular steel baskets. They twist and spiral their way up the building in a way that seems to deny all conventional ideas of structural logic. Given that it is a building which has to meet the onerous demands of Japan’s structural codes that have been devised to deal with the demands of even a once in 400 year earthquake, this was by no means an easy task. In fact, Mutsuro Sasaki the engineer has talked of being handed a impressive sketch by Ito when he first started working on the project. “It seemed unrealistic with irregular tubes supporting several thin plates swaying like seaweed. However, the picture, full of poetry had a powerful impact, and stirred my imagination”.

Sasaki has managed remarkably successfully to realise Ito’s conception of an almost invisible structure. The floors are so open, the structural voids, like woven baskets of tubular steel struts, seem so far removed from the functional demands of a structure, that the Mediathèque has a remarkable lightness and insubstantiality. Some of the voids are devoted to staircases, others are occupied by lifts, others again are just holes rising the height of the building, allowing daylight to penetrate into its very heart, floor by floor bulging out, or twisting inward. The Mediathèque’s floors vary in height and configuration and character, thanks in part to the interiors which have been substantially shaped by the architects and designers that Ito has recruited to help.

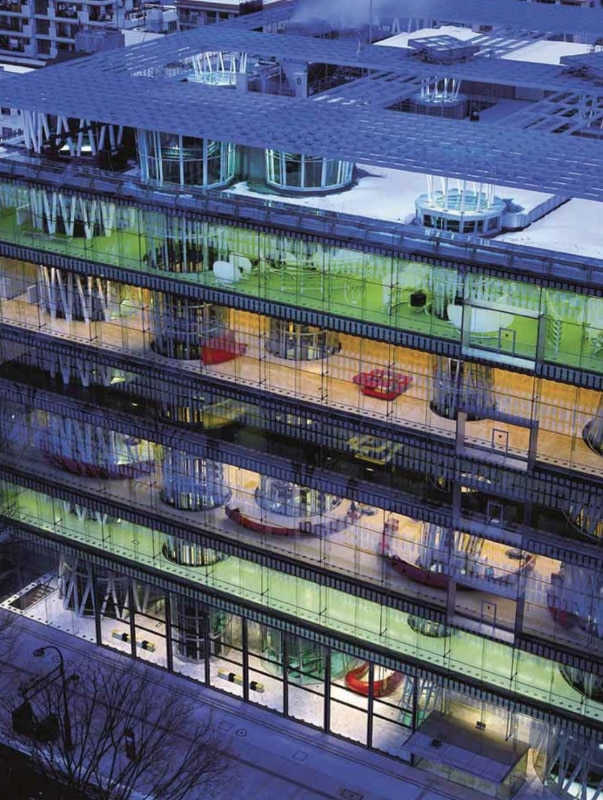

Kazuo Sejima, the architect who began her career in Ito’s office, has done the furniture in the children’s area of the library. Karim Rashid, from New York has made a series of sculptural, almost architecturally scaled furniture objects that bring colour to the mainly monochrome structure, especially the entrance level, which is treated like an open public piazza. And the top floor is carpeted green, at Ross Lovegrove’s suggestion, to create what he calls a Garden of Knowledge. It is a theme taken up in the green tree like shelving system to hold cassettes and cds in this area, while the ceiling here is a random pattern of fluorescent tubes.

This is a remarkable building, one which tries very hard at every level to push architecture in a fresh direction, yet never descends into simple minded exhibitionism. It is very Japanese, and yet also belongs to the international architectural mainstream. It’s beautifully made, and yet it relies on the quality of the ideas underpinning its design rather than the jewel like quality of its detail. It’s spatially rich and complex, it has a remarkable presence, and yet it also hints at a wide gap between its architectural ambition and the homely reality of the activities that will take place inside it.