This article was originally published on Domus 816, June 1999.

Founded in 1903, the Ford Motor Company was classified in 1996 by Fortune 500 as the second biggest company in the world. Annual sales are close on 7 million vehicles, produced or assembled in 30 countries and distributed in more than 200 through a network of 10,500 dealers.

The corporation, made up of Ford, Mercury and Lincoln, also owns Jaguar, Aston Martin Lagonda and Volvo, and has capital interests in Mazda and Kia. It employs more than 370,000 people worldwide. Among the first to believe in the international car market, Ford is now launching a strategic design programme that will need to be matched by a new global product image for the third millennium. And naturally its goal is once again to become, as it was in the days of the mythic Ford T, the world’s leading car maker.

Henry Ford and the universal car

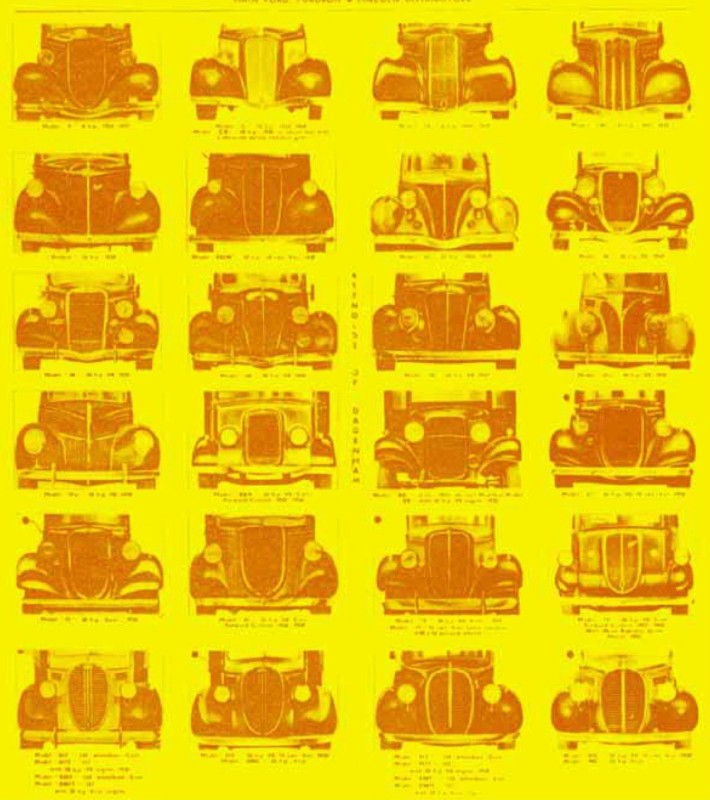

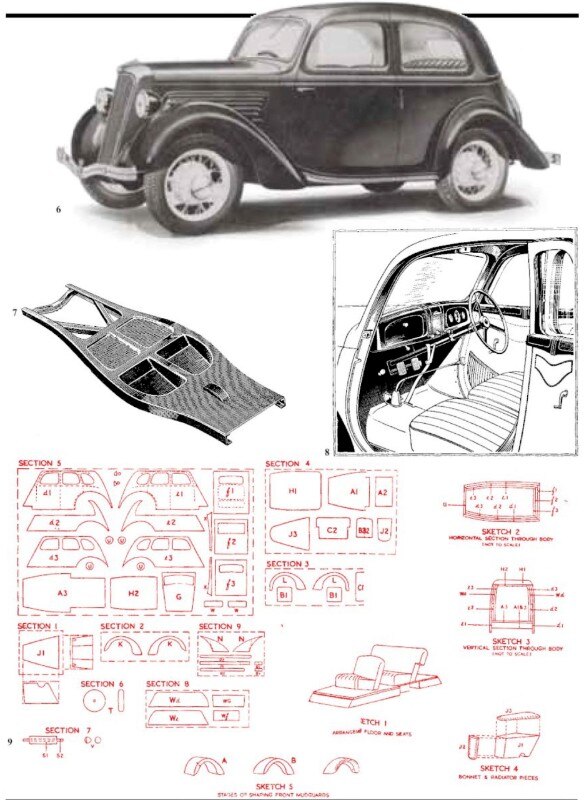

Henry Ford did not invent the automobile or the assembly line. Inspired by a personal vision that put him in a vanguard may ahead of his contemporaries, Ford invented mass mobility. “I will manufacture an automobile for the masses, made with the best materials by the best workers. It will have to be so cheap that nobody will be unable to afford it”. To achieve that end, after twelve years of widely assort engineering designs, he came up with the Ford T, a car whose appearance and design were as anonymous as its manufacturing principle was peculiar, based as it was, on “complete interchangeability of parts and simplicity of interlocking”. Associated with this principle, today taken absolutely for granted, war a constant restructuring of the production cycle In accordance with Taylor’s methods, this was broken down into elementary operations: with the average cycle of a Ford assembler dropping from 514 minutes in 1908 to 2.3 minutes in 1913. At Highland Park that same year, the first experiments with assembly lines were carried out (the idea having been got from Chicago’s slaughterhouses). As a result the cycle further reduced to 1.19 minutes. Production immediately rose. Chassis assembly times were shortened from 12 hours to one and a half, and every ten seconds a finished vehicle came out of the factory. To avoid dead production times, all cars were painted the same rapid-drying, Japan black. In compliance with the legendary directive in force until 1925, when nitro-cellulose paints were introduce, anyone could buy a Ford T in any colour — “as long as it was black”. The results were even more amazing considering that Ford, in contrast to Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” theory pursued a fully vertical production policy: from the mining of raw materials to their processing and transport to the plant, everything was owned by Ford.

The advantages were reflected economically for the company, which in 1914 sold more automobiles than were produced worldwide by all the other makers put together; for the consumer; who saw prices steadily drop— from the initial $850 to the $450 of 1914; and for the workers, who in the same year were offered a daily wage of $5 for eight hours’ work which, dismal though it was, was nevertheless more than twice the going rate in industry at the time. Herein lay the keystone of Fordism, whereby increased exploitation of labour spelt higher productivity and proportionately lower prices to be offset by larger numbers of buyers. And the greater consumer power was in its turn made possible by better wage conditions. All this certainly sped the United Staes on its way toward the economic miracle and grandiose politico-cultural growth of the early 20th century on which modern Americanism was built. On a parallel however, the speed of social and economic revolution was one of the causes of the slump in 1929. From the ashes of that great depression a more modern consumerist behaviour evolved. This had to be match, by a more flexible production system, which Ford only partly managed to exploit. Ford’s idea of a “universal model” — right for everybody and forever —did not in reality withstand the evolution of tastes and the attention to style induced by that very same prosperity that the Fordist market expansion had establish. Alfred Sloan, who had been summoned in 1920 to direct General Motors, realised the importance of ‘appearance’ auto sales. Combined with a corporate restructuring geared to less bureaucracy and more flexibility, he set up a department named Art&Color. To run it he brought in Harley Earl, the inventor of modern car design. Albeit at higher prices, GM succeed in offering aesthetically more attractive cars and with its Chevrolet in 1926, it overtook Ford’s sales and turned out nearly a million cars in that one year alone.

It was the end of a myth. Nineteen years and fifteen million cars after its first appearance, the T, the “Tin Lizzie”, by that time selling at $260, finally left the stage. Production in the 35 Ford plants came to a halt, workers were laid off, and nobody knew what the new model would be like. Marketed, in 1928, that next car, signifying the company’s new face, was called Model A. It was available, needless to say, in seven colours and six different types of bodywork.

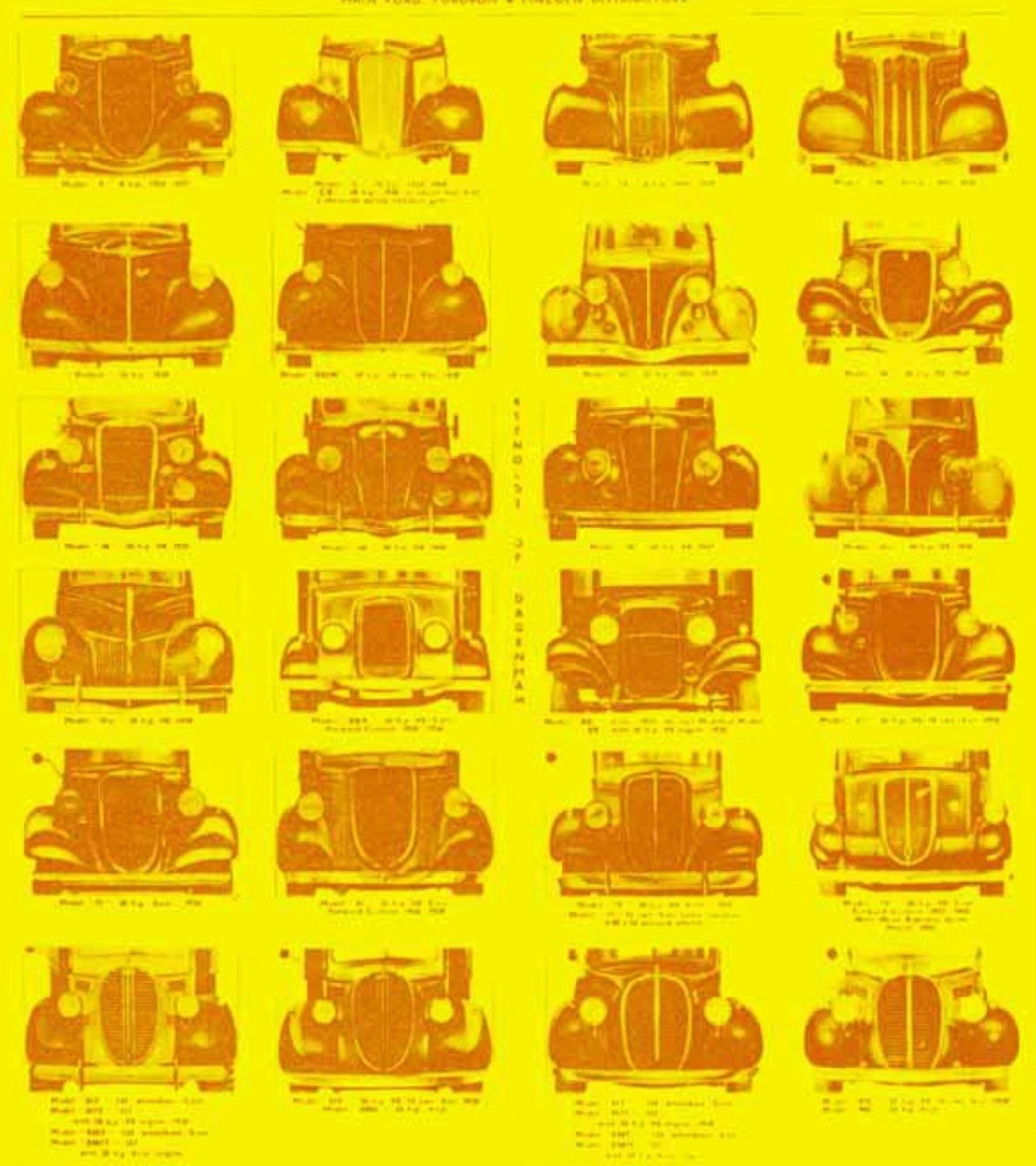

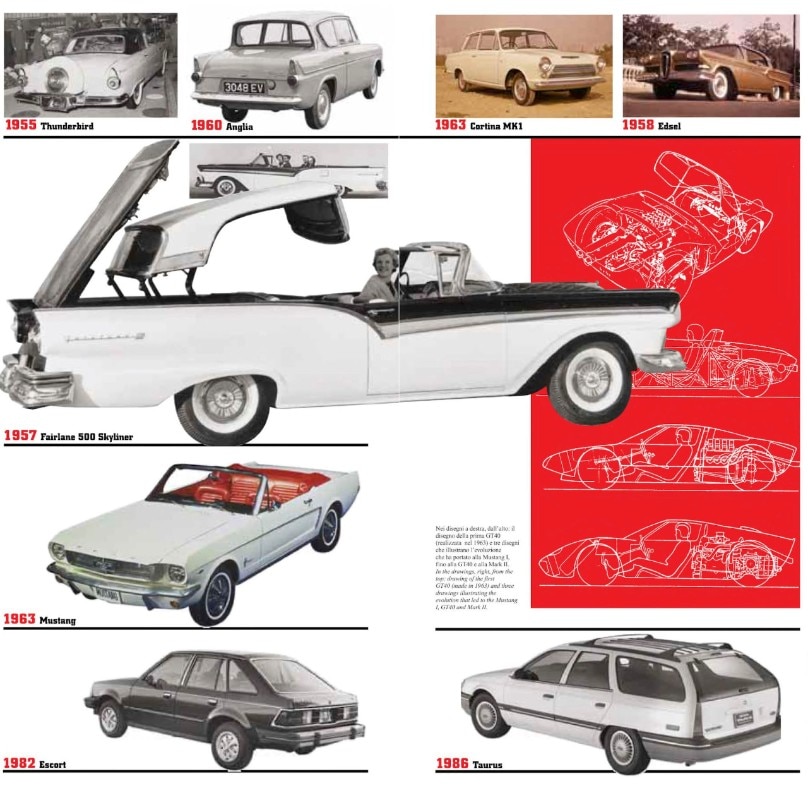

The development of the Ford product in the years that followed was geared rather to the proliferation of models in response to changing consumers tastes, than to the assertion of a lasting brand identity associated with product and position. The decentralisation of production was particularly significant especially in Europe, where the Dagenham and Cologne facilities each pursued their own, often antithetic, sales and design policy. This gave rise on the one hand to a British line of thinking that was almost refined and pretentious, and on the other to a German approach that was more sober and solid, though inspired by American grundeur.

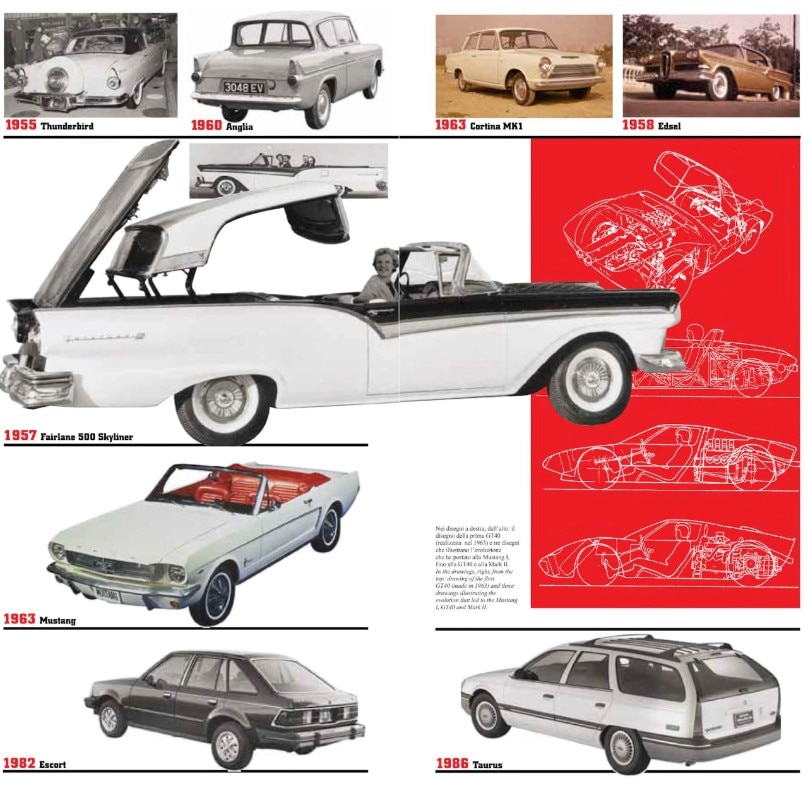

On the whole, in a see-sawing of often original stylistic rediscoveries. anonymous sedans such as those of the Fordor generation, were superimposed on sophisticated niche products, such us the evergreen Thunderbird; and big sales hits, like the mythic Mustang, helped to blot out the memory of sensational flops like that of the Edsel; while utility cars such as the Escort went hand in hand with super-sports models like the GT40.

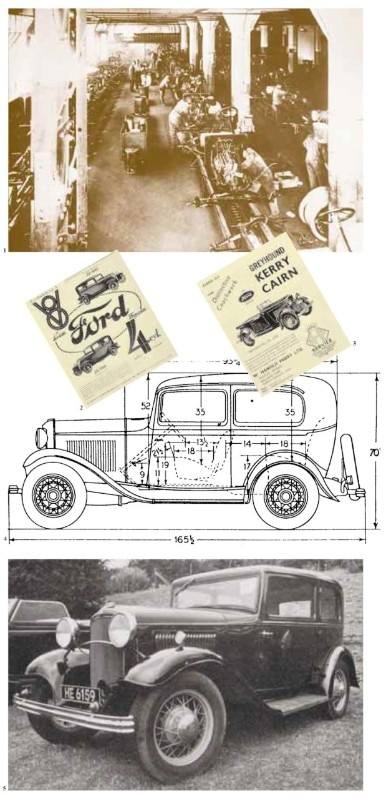

The profound anonymity of the 1970s, which were also years of deep crisis, was followed by an apathy that led to the total loss of sense of the name itself. The first attempt to revitalize it came in the ‘80s, with the launch of the Sierra in Europe and of the Taunus in America. These had a clean, fluent and streamlined design whose initial success was not followed up by an adequate product strategy. The product in fact soon relapsed into its correct but anonymous and undifferentiated look. The general reawakening of the car market in the ‘90s, which could be felt in the growing interest in classic cars as an emotionally, enjoyable asset, led many makers to revive their name image as an added product value. This operation could hardly be implement by Ford, in its role as the “make that wasn’t there”. In this scenario the New Edge programme was launched: in search of a global and permanent requalification.

New Edge design: the hidden function

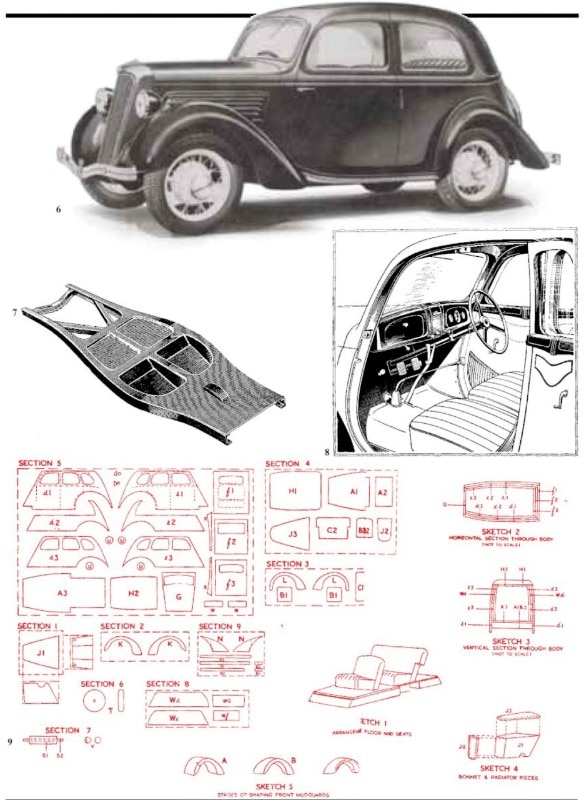

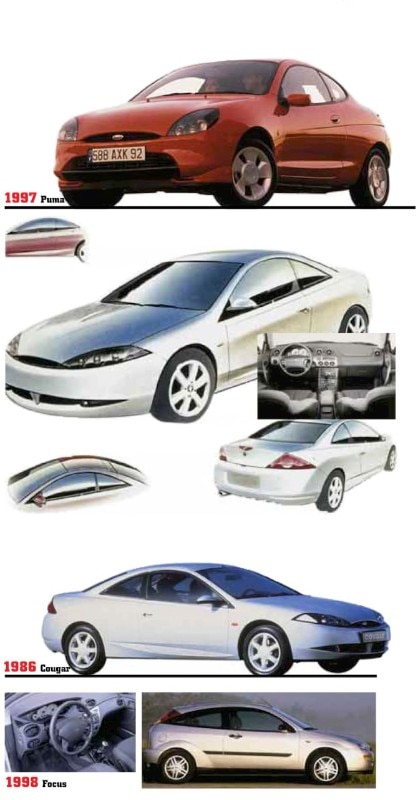

In search of a global make qualification, it was necessary to operate drastically by creating a Ford identity on the drawing-board, not only in terms of description but also of visualisation. To quote John Mays, “the New Edge springs essentially from relatively soft planes by the creation of clean and sharp-edged intersections that help to delineate the softness in a more technical way. Cars with soft lines are generally more friendly than shalp-edged ones. But by adding a touch of precision to soft forms, their technical aspects, dynamic forre and expressiveness are emphasized. The general idea is that this reflects directly on the vehicle's road qualities” — all of which nicely fits the passwords of Ford’s identity: progressive, sincere, lively. The theoretic approach to design is clear: the New Edge is born as a style by analysing current trends and making a digressive synthesis: to collect latent signs in a dichotomic key, uniting concave and convex, soft and hard-edged, square and round, symmetry and asymmetry — while seeking to produce an original mixture capable of withstanding the signs of time.

The calculated balancing of features ought to allow a continuous updating of cars by fully exploiting the matching of different types, markets and tendencies. The prevalent component, the graphic one, lends itself to any number of modulated signs, now light — where more decency is required — now charged — where public niche allows for greater vulgarity. Examination of the four cars presented to date already permits some comparisons. The earnest anti-automobile playfulness of Ka attracts a public with easy and immediate tastes; the sporting ambitions of the Puma are reflected in the greater fluidity of more stylized lines, and the reference to the real GTs is fundamental in boosting the image of the small sports car. The well-outlined solidity of the Focus, which in the sedan and SW versions tends almost to normality, is suited to a wide public interested in a medium car for medium people. The deliberately top-heavy originality of the Cougar is undoubtedly related to the desire for distinction felt by a public at once more mature and more exhibitionist.

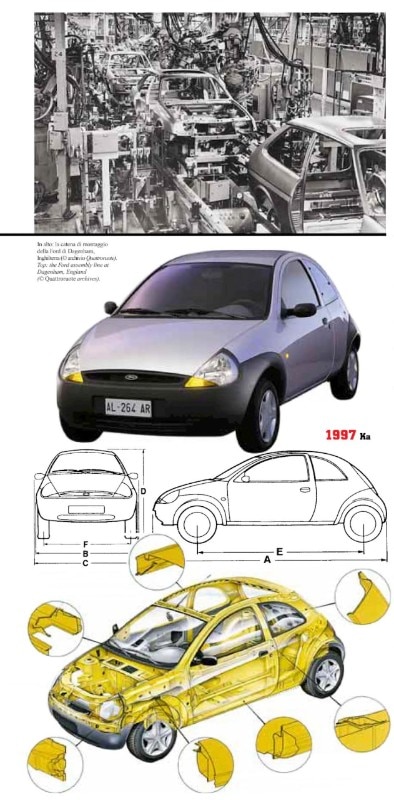

Read in these terms the purpose of New Edge is plainly to create distinction, dynamic force and innovative elegance: a question of style, then? To quote Claude Lobo, former manager of the Ford Small and Medium Vehicle Center, “it is not a matter of style or surface treatment: the New Edge is a way of working. It is true that the clean sharp intersections are created to heighten the character of the car, but they also stem from the desire to improve and facilitate the production process and to give better quality”. Thanks to New Edge, the plate can be stabilized during moulding, reducing rejects in body production time which, in the ease of Ka, comes to 30%. In addition to that, aerodynamic, functional and ergonomic engineering has revised design criteria for the whole package to improve its overall efficiency. Thus in the case of the Ka, the study of ground imprints and the positioning of the wheels on the outer edge of the body made it possible to minimize the steering radius, thus making the car easier to handle; whilst the intelligent bumper panels extended to integrate the mudguard help reduce damage from small parking knocks. In the Focus, passenger space was studied with a new generation RAMSIS software, thus allowing the range to be extended from 4° and up to 99° percentile; the particular positioning of the rear lights creates a deliberate stylistic ‘tick’, at the same time optimizing visibility; and the functionality of the rear part, designed to achieve a strong Kamm effect, produces good aerodynamic results.

The New Edge thus theorizes the hidden function, necessary but no longer sufficient to ‘sell’ the product, and hence destined to remain, in the eyes of the public, a ‘style’. In this must be recognized on the one hand the courage shown by Fords in proposing — though there was no alternative — a new language in place of the hackneyed exploitation of rétro stylistic canons; and a consistent logic in extending it to make it a bearing element of the make identity (a still heavier commitment considering the sales volumes typical of Ford).

On the other, it has to be admired that the car has lost its sense as an independent class of object and design. These cars are objects like any other, well designed, appealing and sleek in their own way. Their sense can be found only in the collectiveness of consumer attitudes accelerated by appearance, at the antipodes to Henry Ford’s concept of universality, though necessary today to the actual survival of the market.

Trademark, markets and strategies. Interview with John Mays

Design Vice-president of Ford, John Mays has been concerned since 1997 with the development of global make strategies for the Ford group. Coordinating the work of a team of some 1000 people spread over 11 studios across the world for 7 auto makes, he is responsible for the development of no less than 25 new cars — what with series and pre-series — and for at least 10 concept-cars per year. Paolo Tumminelli met him at the Ford World Headquarters in Dearborn.

Ford is today a very complex really. Can you make a picture of it?

Ford is in a period of continuous acquisitions, to a point where if you think of a Ford today you don’t think only of the little blue oval any more but of the Ford Motor Company, which owns Mercury and Lincoln in the U.S.A., a major share interest in the Japanese Mazda as well as Jaguar, Aston Martin and Volvo in Europe: all these makes together are under my charge in terms of design. My job is to look at the comprehensive future picture of these makes, keeping them just far enough apart to avoid too many overlappings. The main goal of the pact 14 months has been to create a visualizable make strategy, a sort of visual DNA. To fraction a brand into the factors of form, color, material and texture is very easy if you think, for example, of Jaguar. In the case of Ford it has been more difficult because the image is very confuted: Ford, in the past did a bit of everything generating a rather inconsistent general picture: despite 11 studios in the world no philosophy had ever been worked out, and this is a problem: on the one hand a certain type of European perspective emerged, on the other a more American vision, and then a Japanes, an Australian one...

At a series of meetings the direction of each single car make was decided, along with its design philosophy and essence, both in visual terms and with regard to all the other sensorial perceptions: smell, what people feel when they drive it, the way the doors slam. All these things had to make up the guidelines with which to bring new products into existence. Although this process is still going on, the characteristics of a global and primary Ford strategy can already be spotted: Ford is progressive, sincere and lively, where the liveliness has less to do with the look of the vehicle than with its make-associated values: but the progressiveness is defined in the new edge design, which Ford has already introduced into its European models. Mercury will become more individualistic and much more expressive; this car make was in the past thought of for a mature clientele who wanted a slightly better car than the Ford — and it has been accused of being a Ford with a bit more chrome on it. The make will be reinvented to cater for the young, and will differ not so much in its design — which will remain new edge-oriented — as in the type-range of vehicles offered: not so much traditional sedans as, above all, high-package saloons, cross-training or cross-hybrid vehicles that don’t exist even today on the market. For Lincoln a conscious and very clear decision was taken: in antithesis to Mercedes or BMW, European cars representing Teutonic luxury, the tendency will be to bring back the true American school, which in recent years has become a bit too flamboyant, big and fat. More European dimensions and a clear and clean American design, inspired by the 1961 Continental: a highly contemporary, slim and dynamic compound, thanks to the use of a rear wheel drive that helps to create nobler lines, with restrained front embosses. Mazda will go back to its roots, innovative and aggressive: in a respect for the image attained with success vehicles like the RX-7 and the Miata. The Jaguar possesses a sensual and measured British elegance that will be enhanced without excessive Americanizations. Aston Martin remains a technological leader: with aristocratic materials like natured leather, matched however by high-tech touches — with carbon fiber elements, and space frames. Volta represents in the minds of all customers a sense of safety and family values: in the future we shall be seeing even solider and more full-bodied, sober cars than those of today.

Bob Lutz defined Fords as “normal, cheap, serene, adequate” automobiles. If you look in the collective memory you find just about everything: from the black and unchangeable model T to the mythic and exuberant Mustangs and T-Birds, from the stylistic baldness of Sierra and Taurus to the correct normality of Escort and Taunus. How was it possible to hit on a common denominator?

In reality we have got rid of all this and I believe that in five years it won’t be possible anymore to retrace the link between a Ford past and present. We shall be using history only where it is applicable and important to people, for the rest I shall be sticking to three standards of judgment for our new products, which are: fulfilment of brand values (progress, sincerity, liveliness), difference from competition products, and the meaning they have for customers. This last is the most important point: for many years progressive designs were created without this being related to customer desires. Nowadays there can be no avoiding this immediate connection.

Cars have basically always been progressive. Then later, the rétro was imposed as a means of iconographic revival of the primordial soul of the automobile. You have been almost simultaneously in charge of projects like the New Beetle — typically rétro — and the Audi A6, which may be configured instead as a non-automobile car. What a dichotomic approach!

There’s room for everything, a niche for everything. When I was at Audi, they were making basically four models of cars for a total of around 450,000 sold per year. At Ford we have 76 different models and a total of about 7 million cars per year. In a constellation of this kind it is possible to experiment. Some cars can be very serious, elitist, pragmatic and Teutonic, others can be friendly, accessible. democratic. It’s the same healthy difference that you find between

Alessi and Braun: on the one side cheerful products, on the other tremendously serious.

The Audi A6 is perhaps the first car designed as a “design object”. In its brochure, the Ford Ka is directly related to the world of designer goods. How realistic is the perspective of cars sold and consumed — including stylistically — as objects?

They will become so, totally and not in order to keep up with a trend. Styling as an art form has had its day, and I believe there is still room for true styling in a Jaguar or an Aston Martin, where it is associated with beautiful streamed lines a la Pininfarina or a la Williams Lyon. But when a vehicle is design by highlighting practical or functional aspects — or maybe when it’s a sport-utility — people aren’t looking for pure car-beauty but simply for character; and much of that character comes from an approach addressed more to the product design than to the auto design. Many of our products therefore begin to look like industrial products and in this sense we are encouraging an openness to collaboration with architects, designers, fashion designers, to bearers of new trends and of a different kind of knowledge.

A multiplicity of styles is today matched by a multiplicity of different types. In same ways though, rational car design seems to have fallen by the wayside. If we look outside cars, we see that ‘rational’ minimalism is today a rediscovered and recognized trend. Is there room for. a minimal aesthetic in cars?

Many car makes will indeed have room for design guided by functionality. I can’t tell you what we are working on and for which makes, but we will have product segments with a much more functional content than in the past. Vehicles of this type that are more rational and down-to-earh — and excellent examples are the Panda and the Megagamma — will surely crop up again. Volvo could be a case in point: not dull but highly minimalist. In the US the Lincoln also will be going in this simple direction, like what I like to design. If a line has no reason to exist in a car, then we won’t put it in.

Niches and fragmentation. Will there be a place for a real Ford “World Car” in the future, as the Escort should have been in the 1980s?

There will certainly be world platforms, but cars will be of regional character. A car designed in England will need to look English, one in Sweden Swedish and so on. Our objective is for people getting off a plane anywhere on the planet to be able to recognize even a Ford, which today doesn’t happen. What will its character be like? Well, Ford is an international corporation based in America. For this reason we would like to put across a positive American image, not so much of the excesses (the aesthetic of the “too much”), as rather of the trust and optimism of this nation.