Amid enthusiasm and controversy, in 1889 the Exposition Universelle opened in Paris, certainly celebrating the centenary of the French Revolution, but above all presenting itself to the world marked by an at least unprecedented monument: a 300-meter-tall iron trellis planted along the Seine, with different levels visitors could access by elevator, to admire the panorama of the capital, and the display of national industrial progress orchestrated at the ground level by Charles Garnier, in the different pavilions that filled the Champ de Mars. At the top of the Eiffel Tower – this is the monument we are talking about – the namesake designer would be able to create for himself an apartment, useful for research on air resistance, but above all a more or less conscious experiment in an organization of space according to a plan libre that Le Corbusier would theorize decades later: it was the structural layout to allow it, if not to impose it, characterized as it is by the presence of the iron spatial lattice elements, and the passage of the large elevator shaft. Most likely Eiffel did not sleep a single night in there, using it mainly as a representative space where he would also host Thomas Edison upon his visit in the year of the Expo; the visionary nature of his concept was nonetheless explored by Domus in September 1981, on issue 620.

Eiffel's Belvedere

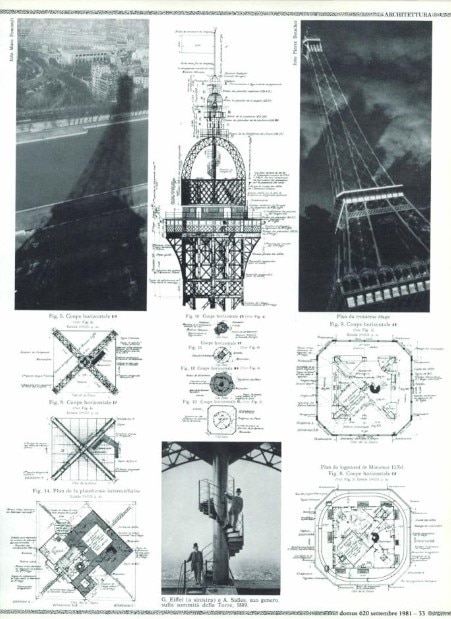

A design variant and the assent of the 1980 Expo commissioners allowed Gustave Alexandre Eiffel to bag for himself a part of the terrace on the “Tour de 300 mètres”, cluttered with the final buttresses and the service rooms of the most complicated elevator in history. This part consisted of the square space — measuring approximately 10 by 10 metres — raised one floor above the third platform level and situated underneath the large diagonal girders of the delicate system of hinging overhead.

This decision to build himself a house, albeit for special purposes (some of the rooms in fact had to be used for research on air resistance), at the top of his own national monument and in an architectural atmosphere never previously attained, obliged this resolute user and designer to shelve any formal or constructional solutions not capable of coming to terms with those heights and with the wind of the “ville”. Another reason was to avoid having to witness the premature collapse of the dream of a lifetime, of what was surely the true inspiration behind such a daring scheme: the unconscious desire to see the inhabited context of his own illustrious existence as an inventor removed at last from the terrifying, dumb desert of stones in the labyrinth of history, and to be able to admire it, in splendid isolation, against the adventurous vastness of the cosmos alone. It mattered little if to obtain this result the object of his innermost thoughts may have appeared to some as the architectural parasite of his greatest undertaking.

The real point of the matter, which makes this remarkable “logement” an “architectural case” hitherto mysteriously buried in archives despite the outsanding symbol to which it belongs, is that, although its creator was probably unaware of the fact, it indicated and anticipated the lines of a very much more important “transformation”.

With the liberation of space in this house from its ancient telluric base, Le Corbusier’s “Vers une architecture” had in fact, at a height of 300 metres, already started here. A plan of such clear abstract intelligence was able, moreover, to confirm these prospects and to herald new and unforeseeable spatial breakthroughs. The adoption of an aerial constructional system, that drew its still confused and ingenuous freedom from the endless tangle of a new technological existence lifted into the Paris sky, at last spelt the inevitability of a becoming which nobody could exactly forecast. To be sure, those who refused to recognize the undoubted novelties of this “logement” – a “spatial dwelling” for those times more than a “house of earthly beings” – and to give it credit for the future, had already shown their failure to understand the historical reasons for that technological “Locus Solus” which Raymond Roussel was not long in bringing to light.

Apart from the fact that they could not in any case avoid the ado caused by such a vast feat, those opposed to it became consciously or unconsciously prisoners of that swamp of wild dreams of “past progress” which the dilettantesque and irresponsible historicism of Charles Garnier had created at the very foot of the “Tour-Solei”l. But is was precisely this “Histoire de la maison” and its not very reliable pavilions which Eiffel had wanted to contest by fitting out the first of the “vaisseaux-fantôme à habiter” of the new times. By choosing a shade (the tower) different from the millenary shade of the house, this forgotten “logement” had, amongst other things, begun to question the internal and external representation of that house. Its designer had shown that he preferred the “shade” to the “prey”.