“The almost maniacal desire for perfection which makes it seem like a machine with every detail calculated; or rather, an enormous industrial design object”: the words by Benedetto Gravagnuolo summarize with great effectiveness the nature of the Palazzo delle Poste designed by Giuseppe Vaccaro and Gino Franzi between 1933 and 1936. From the lenticular façade to the full-height glazing that seems to immerse itself in it without any material discontinuity, everything makes this building – now a presence in history textbooks on Italian architecture – both a monument and a case of uniqueness in the panorama of Italian rationalism, impossible to ascribe flatly to the register of fascist architecture just as it is impossible to do for its relationship with the urban context, the child of great redevelopment plans born in the late 19th century and completed after the war. A peculiarity, also made up of multiple and not obvious inspirations, both Italian and international, of which the photos by Mimmo Jodice help to provide a new narration, collected in a work that made its appearance on Domus on issue 693, April 1988.

The Palazzo delle Poste, Naples, 1933-36

Architecture of a high aesthetic level is not always the work of famous architects or the result of exemplary plans. It occasionally, though rarely, happens questionable urbanistic work becomes quality construction and is recognized as such, despite the limits which surround it.

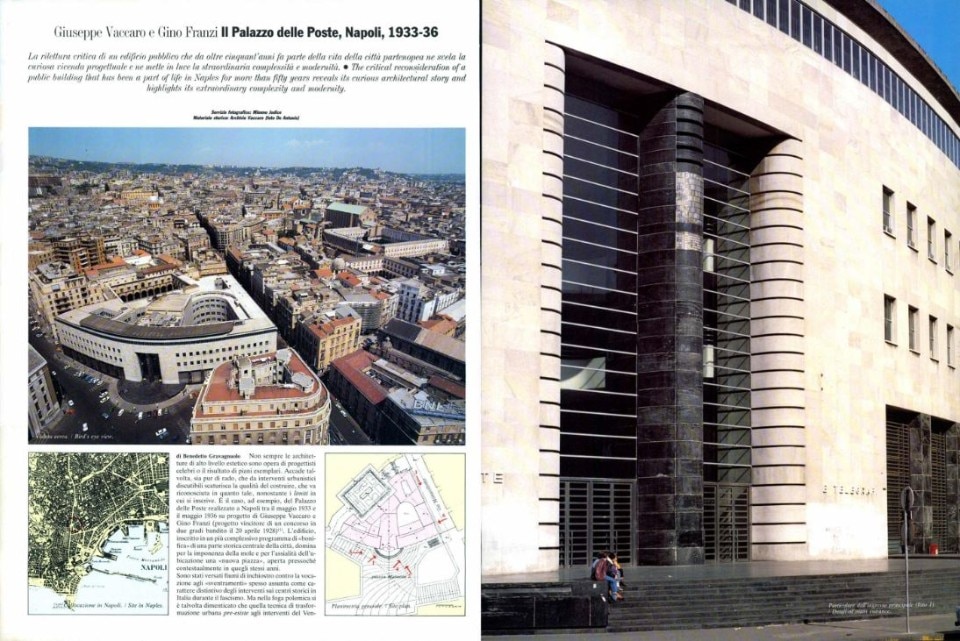

This, for example, is the case with the Post Office building created in Napoli between May 1933 and May 1936 from a project by Giuseppe Vaccaro and Gino Franzi (a plan which won a two part competition announced on April 20th 1928) (1). The building, which was part of a more complex programme of reclamation of a part of the historic centre of the city, dominates a “new square” opened during more or less the same period with its mass and the axiality of the site.

Streams of ink have been spent protesting against the demolition of historic centres, often considered characteristic of Italy during the fascist period. But in this passion of polemic one sometimes forgets that that technique of urban intervention existed before the Twenties, co-exists with co-eval European planning, and will continue to persist even after the fall of the fascist regime. So that in this specific case one can easily show that “the reclamation of the Carità district” is no less than the logical 9onclusion of a radically innovative strategy concerning the street system of Naples which was begun with the Restoration Plan of 1885; it was confirmed with a detailed programme on the zone in 1913, prefiguring the work carried out in the Thirties and finally degenerates into the chaotic completion of the district carried out in the Fifties.

The vulgarity of building speculation in the postwar period does certainly not justify the mistakes made with the beginning of reclamation in December 1930. Among these above all is that of destroying the minute historic structure close to the Renaissance building of “Olivetani” monks, in order to make space for a “hygienic” Centre of Institutions, considered representative of the regime (or a police headquarters, buildings for the tax authorities, the Province, the crippled... or the Post Office).

However – and it does not seem a paradox – the difficulties of the context within which the architects Vaccaro and Franzi have to work (urbanistic and political) give their project elements of particular interest. If nothing else because the design of the Post Office building was conceived as an attempt to use architecture to redeem the limits imposed at the outset. In its own form the building condenses the answers to a series of urbanistic questions which run from optical attenuation of the irregularity of the site, to intelligent setting of preexisting architecture within the new composition, to the original declension of the unavoidable request for monumentality. And what is most fascinating is that this acrobacy of design is balanced on a rasor of “modernity”, that is to say, on the declared intention of an absolute essentiality of language, apparently incompatible with the themes of cicumstances.

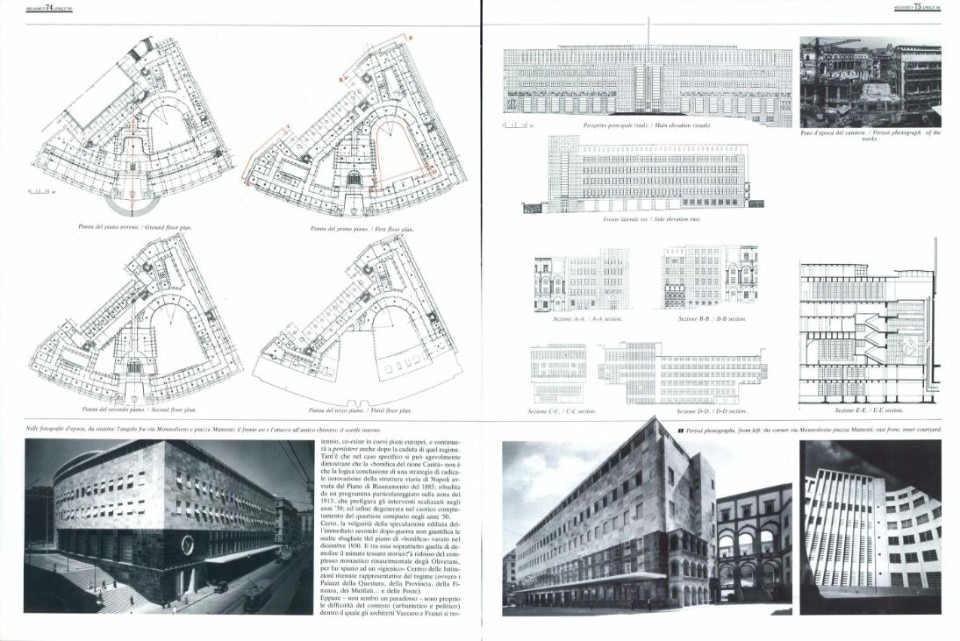

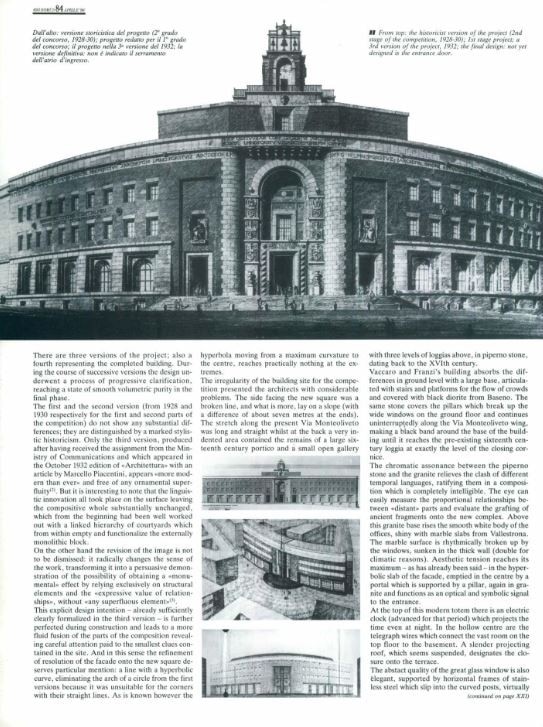

There are three versions of the project; also a fourth representing the completed building. During the course of successive versions the design underwent a process of progressive clarification, reaching a state of smooth volumetric purity in the final phase.

The first and the second version (from 1928 and 1930 respectively for the first and second parts of the competition) do not show any substantial differences; they are distinguished by a marked stylistic historicism. Only the third version, produced after having received the assignment from the Ministry of Communications and which appeared in the October 1932 edition of “Architettura” with an article by Marcello Piacentini, appears “more modern than ever” and free of any ornamental superfluity (2) . But it is interesting to note that the linguistic innovation all took place on the surface leaving the compositive whole substantially unchanged, which from the beginning had been well worked out with a linked hierarchy of courtyards which from within empty and functionalize the externally monolithic block.

On the other hand the revision of the image is not to be dismissed: it radically changes the sense of the work, transforming it into a persuasive demonstration of the possibility of obtaining a “monumentai” effect by relying exclusively on structural elements and the “expressive value of relationships”, without “any superfluous element”(3).

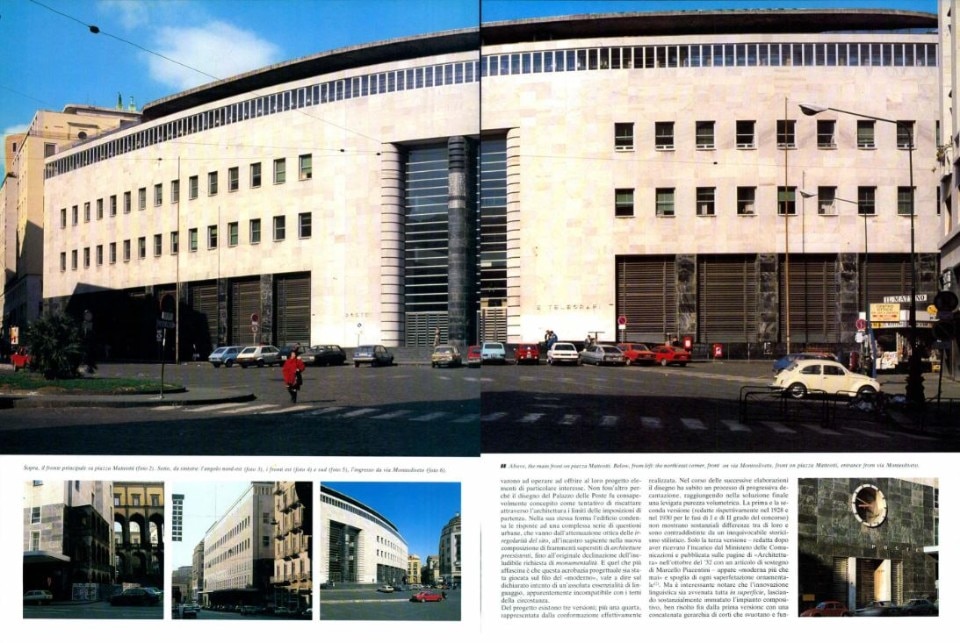

This explicit design intention – already sufficiently clearly formalized in the third version – is further perfected during construction and leads to a more fluid fusion of the parts of the composition revealing careful attention paid to the smallest clues contained in the site. And in this sense the refinement of resolution of the facade onto the new square deserves particular mention: a line with a hyperbolic curve, eliminating the arch of a circle from the first versions because it was unsuitable for the corners with their straight lines. As is known however the hyperbola moving from a maximum curvature to the centre, reaches practically nothing at the extremes.

The irregularity of the building site for the competition presented the architects with considerable problems. The side facing the new square was a broken line, and what is more, lay on a slope (with a difference of about seven metres at the ends). The stretch along the present Via Monteoliveto was long and straight whilst at the back a very indented area contained the remains of a large sixteenth century portico and a small open gallery with three levels of loggias above, in piperno stone, dating back to the XVIth century. Vaccaro and Franzi's building absorbs the differences in ground level with a large base, articulated with stairs and platforms for the flow of crowds and covered with black diorite from Baseno. The same stone covers the pillars which break up the wide windows on the ground floor and continues uninterruptedly along the Via Monteoliveto wing, making a black band around the base of the building until it reaches the pre-existing sixteenth century loggia at exactly the level of the closing cornice.

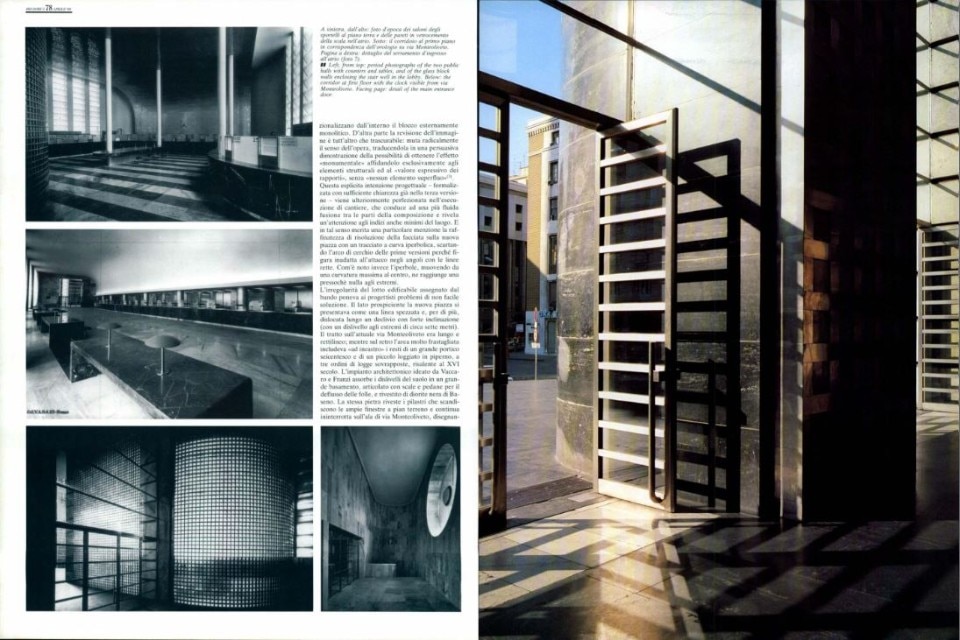

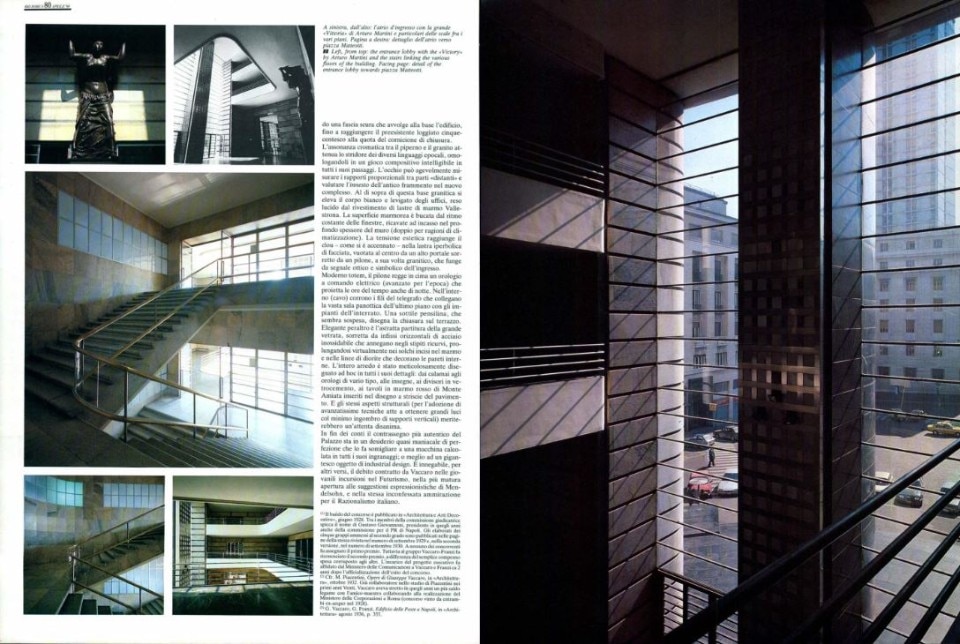

The chromatic assonance between the piperno stone and the granite relieves the clash of different temporal languages, ratifying them in a composition which is completely intelligible. The eye can easily measure the proportional relationships between “distant” parts and evaluate the grafting of ancient fragments onto the new complex. Above this granite base rises the smooth white body of the offices, shiny with marble slabs from Vallestrona. The marble surface is rhythmically broken up by the windows, sunken in the thick wall (double for climatic reasons). Aesthetic tension reaches its maximum – as has already been said – in the hyperbolic slab of the facade, emptied in the centre by a portal which is supported by a pillar, again in granite and functions as an optical and symbolic signal to the entrance.

At the top of this modern totem there is an electric clock (advanced for that period) which projects the time even at night. In the hollow centre are the telegraph wires which connect the vast room on the top floor to the basement. A slender projecting roof, which seems suspended, designates the closure onto the terrace.

The abstact quality of the great glass window is also elegant, supported by horizontal frames of stainless steel which slip into the curved posts, virtually Stretching into the grooves cut in the marble and the lines of diorite, which decorate the walls inside. The entire furnishing was meticulously designed in every detail: inkwells, various types of clocks, signs, partition walls in glass blocks, tables in red marble from Monte Amiata placed on the striped floor. And the same structural aspects (because of the use of advanced techniques to obtain much light with minimun clutter of vertical supports) deserve careful analysis. Finally, the most authentic distinguishing feature of the building is the almost maniacal desire for perfection which makes it seem like a machine with every detail calculated; or rather, an enormous industrial design object. It is undeniable that in some ways Vaccaro owes a debt to his youthful incursions into Futurism, in the more mature openness to the expressionist ideas of Mendelsohn and in the same unconfessed admiration for Italian Raionalism.

(1) The announcement of the competition is published in “Architettura e Arti Decorative”, June 1928. A prominent name in the jury is Gustavo Giovannoni, at that time President of the Planning Commission for Napoli. The plans presented by the five groups admitted to the second phase of the competition are published in the same magazine in September 1929, and in the second version in September 1930, The first prize was not awarded. However the Vaccaro-Franzi group was given the second prize instead of the payment of expenses offered to the others. Responsibility for the project was given to Vaccaro and Franzi by the Ministry of Communications two years after the official results of the competition.

(2) See: M. Piacentini, Opere di Giuseppe Vaccaro, in “Architettura”, October 1932. Working in Piacentini’s studio in the early Twenties Vaccaro established a close relationship with his teacher-friend, assisting in the construction of the Ministry of Corporations in Rome (a competition won by both ex-equo in 1928).

(3) G. Vaccaro, G. Pranzi, Edificio delle Poste a Napoli, in “Architettura”, August 1936, p. 355.

Photographic report: Mimmo Jodice, Historical material: Archivio Vaccaro (photo De Antonis)