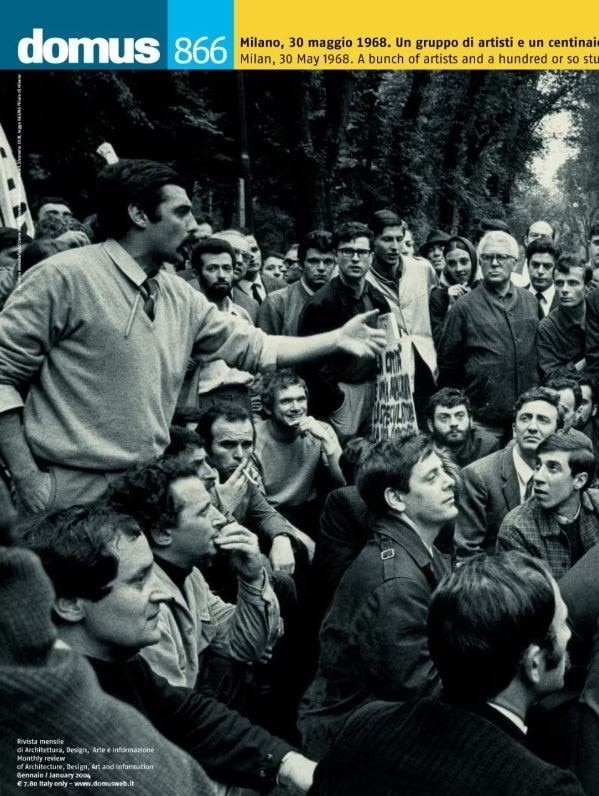

This editorial was published on Domus 866 in January 2004.

The question of style may be roughly stated as follows: should an object be shown with all the attachments that make it possible? Or should it be delineated to a point where it shines like a brightly lit foreground against a shadowy background? In the first case, we are talking about things in the old etymological sense of issues, matters of concern, which force people to focus on what they disagree about yet have in common. In the second case, we are talking about objects – about what is unquestionably out there, mastered and known, that can be accepted as facts. This is a matter of philosophy and politics, but also of art and design and hence of civilization.

The German sociologist Ulrich Beck has distinguished between what he calls a ‘first modernity’, populated mainly with objects, and a ‘second modernity’, invaded more and more by things, by what he calls ‘risky’ objects. This does not simply mean that we, in our opulent societies, are living more dangerous lives than before, but that all objects have taken on another quality: they no longer remain inside the narrow boundaries within which modernism wanted to confine them, but are breaking out. To speak like an economist: nobody can ‘externalize’ for long what threatens the inside definition of objects as they did —or tried to do— during the modernist period; objects now carry involuntary implications that are visible even though they do not yet exist.

For instance, the whole of Europe is debating the dangers of genetically modified crops, though they have not killed anyone yet. This is not proof of irrationality but of the new status of the object. No one any longer seems able to imagine a neatly defined object that might later have indirect effects. Long in advance, while the disputed thing is being designed, invented, tested and tried out, all its legal, medical, agricultural and economic ramifications are being argued publicly.

The ‘bald’ objects of the recent past have become dishevelled, hairy, networky ‘things’.

Everywhere, matters of fact are slowly graduating to the new status of matters of concern: the site in southern Italy that was to have stored radioactive waste, the proof that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction, how to restore Michelangelo’s David…

This tidal change in civilization has an interesting retrospective consequence on how to assess so-called modern styles. Everyone agrees they offered powerful ways of eliminating decoration, acknowledging the influence of regionalism and nationalism, and shaking off the stifling remnants of mythologies long dead. But it’s also clear that they were never simply about architecture or design: they always offered a philosophy of objectivity. Such a connection was never clearer than in the Bauhaus movement, which sought explicitly to invent a philosophy of science, a theory of art as well as principles of education, economics and politics. The search for such coherence underpinned the civilizing effects of the modern style, opposing the dramatic resurgence of what had been called ‘archaism’ and ‘irrationality’.

Long in advance, while the disputed thing is being designed(…), all its ramifications are being argued publicly. The ‘bald’ objects of the recent past have become dishevelled, hairy, networky ‘things’.

Thus, if we are correct in saying that this general philosophy of objectivity is now changing, that we have never been modern, that a second modernization is under way and will transform all objects into things, all matters of fact into matters of concern, then what does it mean for modern styles? From the vantage point of the present, we see now that they always rejected, externalized and ignored all the attachments that enabled the efficiency, efficacy, elegance and functionality, of which they had always been so proud, to exist.

In effect, the battle with decoration dissimulated another fight against entanglement. It’s one thing to offer the functional shape of a modernist skyscraper against the horrible doodles of a disgusting past, but it’s quite another to design a shape which ignores everything that keeps a neighborhood alive. It’s one thing to invent a pure and uncontaminated scientific vocabulary in contrast to the horrible vagueness of past metaphysics, but it’s quite another to exclude the many impure languages that allow real sciences to be empirical for good.

The adjective ‘modern’ can be understood in two ways: that which is contemporary or that which breaks with the past. A suspicion now arises: what if the various modernist styles had never been contemporary in and of themselves? Their obsession with the past (if only to break with it) would have blinded them to their own lack of inscription in the present. The word ‘emancipation’ contains a reserve of freedom that is still captive and has not really been liberated by modernism.

It is a word that now requires quotation marks, as though the fight against the shackles of the past had always hidden a much more demanding task: of selecting good from bad attachments, confused with an impossible choice between attachment and no attachment.

Hence the question I want to raise: what is a style – in the broadest civilizing sense of the term – that would at last be contemporary, in and of itself? A style, that is, in the philosophy of science, in architecture, politics, economics, design and art, that would internalize what the modern styles had always externalized, so anxious were they to ‘get rid of’ the externalities? Contrary to what postmodernists imply, modernism is not something of the past that should be overcome, deconstructed or simply abandoned. The problem of the first modernity is its obsession with the past. The time may have come, at last, to consider the future. Provided it can catch up with its time — obviously the most difficult task for modernists.