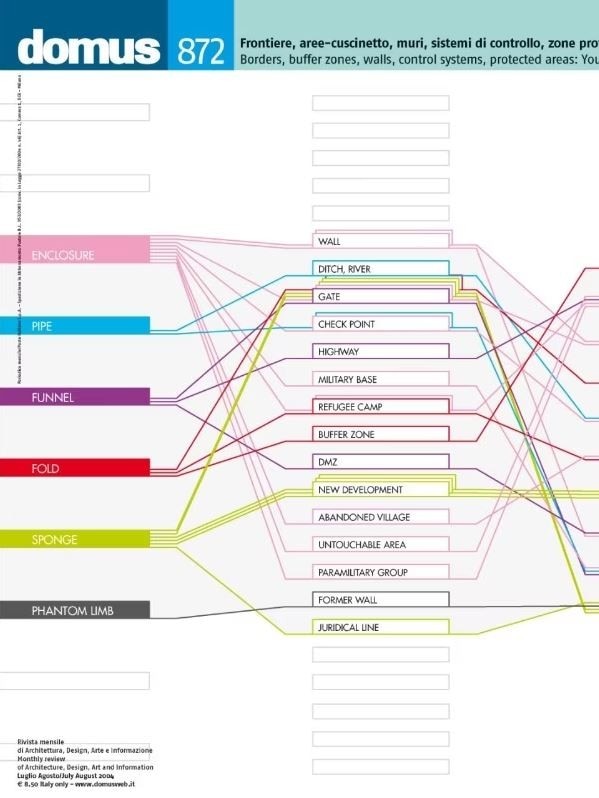

This editorial was published on Domus 872 in July 2004.

In his somewhat gloomy masterpiece on the history of modernist painting, Farewell to an Idea, T.J. Clark explains that the Modern is our Antiquity: an epoch already so far away that it’s difficult to recapture how we felt when we were modern, when we were breaking courageously with the past, when we were following avantgardes, when we were fighting against hordes of philistines and other reactionaries. The adjective ‘modern’ — as in modern art, modern architecture — has become so dated, that museums dedicated to contemporary movements have slowly been overtaken by history and have now been turned into repositories of the past. For instance, the Museum of Modern Art in the Pompidou Centre in Paris is viewed more and more as fulfilling the same duties for the 20th century as the Musée d’Orsay does for the 19th, that is reminding visitors of a glory long gone.

It is strange for people of my generation to feel the cold breeze of history on our necks. Has history accelerated so much that we should start building museums for the first decade of the 21st century? Has the cult of the past degenerated to the point of entering the moment of “instant antiquity”? Or is it still the modernist obsession with the quick passage of time that is forcing us through this planned obsolescence of styles and movements?

The perspective might change slightly if we accept the hypothesis, that I made a few years ago, that “we have never been modern”. Although modernism has been a powerful and efficacious interpretation of the last three centuries, it cannot be taken at face value as a description of what happened. If I am right, then there has always been an official version of modernism and a more hidden one. For instance, just at the time when Descartes devised the famous ‘ego cogito’ (‘I think’), scientists invented the first large-scale collaborative network consisting of laboratories, academies and scholarly magazines. It’s just when the idea of an isolated thinker becomes outdated that the greatest of them recreates the whole world while isolated before his Dutch stove.

Similarly, just when Kant imagined the Copernican Revolution through a world made out of the categories of the Transcendental Ego, another Revolution, the Industrial one, was subverting any clear distinction between objects and subjects forever. Which layer of modernity should one believe in then? The one that defines the isolated thinker or the one that brings into existence the first European wide ‘collaboratory’? Which track should we follow, the one that draws the categories of the human mind or the one that traces the worldwide expansion of Europe to the whole Earth? Between the two movements there exists no obvious relation except that the first is a clear negation of the second.

This uncertainty about two entirely opposite traits of modernism can be seen at every point of the rather short modernist parenthesis. As Adolf Max Vogt has shown in his fascinating book on the psychogenesis of Le Corbusier, this arch modernist, this icon of modern architecture was dreaming only of primitive huts built on wooden stakes like those inhabited by the prehistoric people of Lake Neuchatel where he had spent his youth.3 Primitivism, the obsession of breaking with the past, the nostalgic appeal to historicisation are as much features of modernism as its declared obsession for reason, calculation, efficacy and factuality. As for Futurism, we know all too well how much it was linked to the archaic return of the past.

It’s probably because of this ambivalence that modernists were never able to be, so to speak, contemporaries of themselves. They were never quite sure what it meant to be ‘of their time’. While Baudelaire invented the role of the modernist artist, he carefully excised out of his translation of Edgar Allan Poe everything that made Poe a true contemporary of science and technology. To be modern is always to be out of place.

This is never clearer than in the theme of the revolution in science, in politics, in technology and in art. The ambiguity is built into the very etymology of the word ‘revolution’ that means simultaneously more of the same and what should never be the same. For centuries the word had designated the cyclical return of seasons and political regimes or the circular movement of planetary bodies. Only later, after scientists had used the word for their own scientific revolution, did the word take the opposite meaning of a fresh break with the past, the radical beginning from a clean tabula rasa.

But as Bernard Yack has so forcefully demonstrated, the word revolution takes its most deadly meaning early in the 19th-century when thinkers, disappointed by the French revolution, began to merge the religious theme of conversion, apocalyptic dreams of regeneration, artistic metaphors of recreation, and started talking about a new figure of man.

The question was no longer to just change political institutions, it was now humanity itself in its basic components that had to be recreated anew: from now on, no one should be content with less. As Yack shows, this desperate hope for total regeneration led not only to disappointment — humanity, not very surprisingly, kept coming back to its usual self — but also to a debilitating obsession for the attachments of the past that has become so typical of modernism. The passion for being in the avant-garde is only the flip side of another passion for not being contaminated by the stains of a disgusting antiquity.

Once it’s recognised that we have never been modern, it may become possible to imagine a solution to modernism and to take positively the demise of the revolutionary theme. Instead of artificially prolonging modernism by turning it into a topic for museums, instead of complaining that young generations have abandoned the revolutionary urge of their elders, it might be more rewarding to recognise modernism for what it has always been: a juvenile and pathetic effort to deny what it had been doing all over the world. Its dream of emancipation has always been counteracted by an opposite movement of attachment. Because it was turned so thoroughly toward the past with which it wanted to break, it has run blindly through history, producing in its wake very strange hybrids, mixing up all periods, confusing all sort of epochs.

In writing Farewell to an Idea, Clark has shown a great nostalgia for the grandiose ideas of modernism. But another task remains possible: artists, scientists, politicians and citizens could turn not towards the past but towards the future, so that they become, at long last, contemporaries of themselves and commit the sins of history with their eyes wide open.

Welcome to a new Idea: the future?