The strange figure of St George holds a spell over the city of Venice where he is much worshipped — especially on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore where the Cini Foundation recently held its “dialoghi”. The saint’s legendary achievements have been used by all sorts of warring parties, from Cappadocian Christians and English kings, to Venetian doges and Catholic popes. Though his tomb in the Palestinian town of Lod is revered by Muslims under the name of Al Khidr, “The Verdant One”, it has not prevented him from becoming the symbol of the “clash of civilisations” between Islam and Christian “crusaders”.

It’s under the guise of the greatest of all Moor-slayers that he is depicted in the Venetian palaces, not to mention the precious painting done by Carpaccio that is hidden in the papal room inside the church built by Palladio. In that scene, the dragon is cleanly dispatched, the princess rescued, and the Muslims ready for conversion.

But when an audience gathered for a meeting there in September, they noticed the strangest avatar in Saint George’s long history. The huge statue of the saint on top of the miraculous cupola had been struck by lightning. While the dragon was still there crawling under the saint’s feet along with the Roman army officer in full battle gear, the lance used to slain the enemy was gone. It was quite a sight to take in for a group of scholars assembled to discuss “the ecology of good and bad government”. In this time of “war against terror”, the saint had become - thanks to the wrath of the elements - disarmingly frank: “Beware of which dragon you declare the enemy; you too might be struck by lighting!”

As Peter Sloterdijk ironically said, even American troops cannot parachute an 'inflatable Parliament' to deliver to the traumatised citizens of Iraq the benefits of an 'instant democracy'.

It is true that recently it has become difficult to detect our real enemies. While we were modern, democracy was the mere extension to everyone of the rights under the vast dome formed by the global Parliament of all those who were enlightened. It was a grandiose dream to remember while the voices of the orators resonated through the perfect refectory, designed also by Palladio. But this democratic ideal has been somewhat shattered now that there is no Globe any more. As Peter Sloterdijk ironically said during the meeting, even American troops cannot parachute an “inflatable Parliament” to deliver to the traumatised citizens of Iraq the benefits of an “instant democracy”.

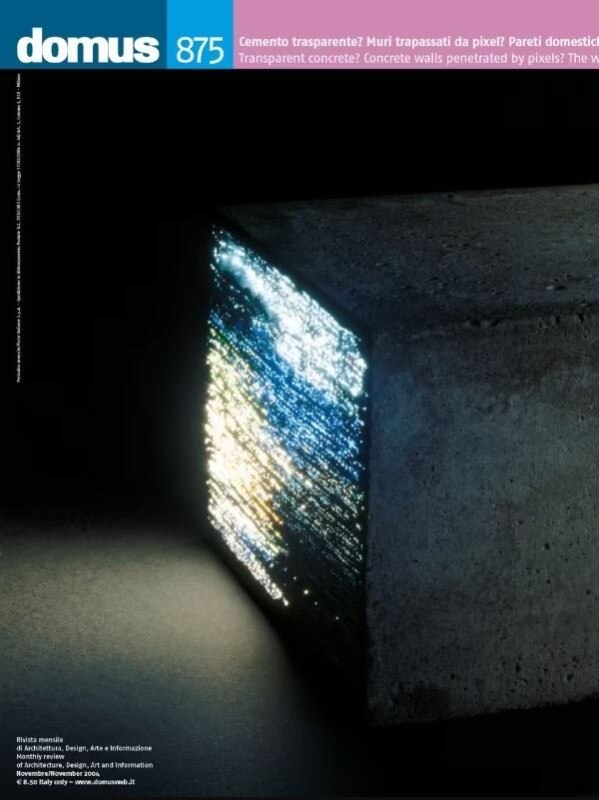

During the three days of meetings, it was as if every one of the invited scholars —along with some uninvited hecklers— made sure that the peaceful ideal of democracy was not obtained too quickly or too cheaply. They insisted that those in the name of whom they talked —Amazonian Indians, ancient Chinese sages, present day mullahs— would no doubt refuse to take a seat in some ready-made assembly. They would first want to redesign everything, including the shape of the room and the whole technology of the gathering. They might even contest the very value of being assembled. To be represented as one people under the same roof requires the strangest and rarest of all ecologies, something as fragile and risky as the survival inside a glasshouse of many foreign and antagonistic plants.

According to Philippe Descola, a large section of humanity simply refuses to think of itself in political terms. Becoming part of a “polis”, forming a civic society, or opting to be a cell of a Great Leviathan are not universal desires that a benign UNESCO can simply take for granted. It’s a rare and fragile peculiarity of our own climates. The atmosphere of democracy is not as obvious as the air we breathe, but a contrived and artificial air conditioning system that would make most people on earth suffocate. Not a very good starting point for an attempt at redefining what it is to live together under one single roof!

The peace perspective did not get better when François Jullien showed that the founders of Chinese thought never elaborated on the notions of politics, dissent, representation, rhetoric, contestation and parliament! The question is not simply to locate the peculiar ways in which the Chinese fit into a vast ecumenical open-minded world democracy. According to him, the Chinese don’t want simply to be different; they want to remain indifferent to the European ways of thinking politically. At which point the puzzled audience was simply requested to imagine not an assembly, or even an assembly of ways of assembling, but an assembly of ways of dissembling. How could such a gathering be achieved? How can democracy be endowed with such a large stomach? Some began to regret that Saint George had lost his weapon-brandishing arm.

Perspectives for peace got even worse when Gilles Kepel shifted the audience’s attention to the damning connotations of the word “democracy” in many of the warring Arab nations. Not only do they possess no home grown idea of independent civil society, but even the notions of a “city” and of a “people” made of “citizens” on their way to “democracy” are imported foreign products. This doesn’t mean that they cannot be accepted but that a common assembly cannot be quickly set up. There is no “inflatable Parliament” that can be parachuted into those regions either. How does one assemble in a common world those for whom the word “Damakrata” sounds more like a term of abuse and those for whom it summarises the greatest ideal from Pericles to Rawls? Should it not be more reasonable to abandon altogether the search for one common world and to let all the dragonslayers rearm themselves?

To be represented as one people under the same roof requires the strangest and rarest of all ecologies, something as fragile and risky as the survival inside a glasshouse of many foreign and antagonistic plants.

This of course would be counting without the atmospheric conditions of the island of San Giorgio, the miracle built just across from the Venetian miracle. Besides the church and the Tiepolo exhibit beneath it, the small exhibit entitled “Iconography of the Good and Bad Government” might offer a solution to the difficulties of gathering so many recalcitrant ways of assembling. It turns out that the Serenissima has for eight centuries thought of itself as the very incarnation of Good Government. Through the works of art displayed in the show, it becomes clear to the visitor that this former world power has managed to keep alive a complex machinery of cohabitation whose technology of flexibility and resistance is still visible today. Of course, democracy should be impossible, but then so should Venice. Yet it lies there in the golden sunset while Saint George continues to protect this fragile place, even without his lance.