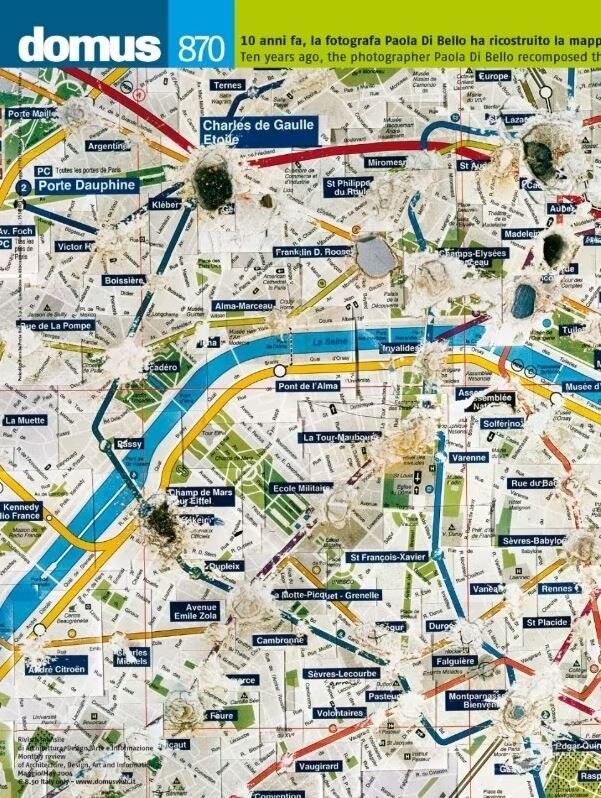

This editorial was published on Domus 870 in May 2004.

Why is it so difficult to interpret digitality? Is the transformation of everything into strings of 0s and 1s propelling all of us, poor mortal souls, into the formal paradise of virtuality? Or is it, on the contrary, giving a new materiality to everything formal and spiritual? It’s hard to tell which one of those two ‘hypes’ is best able to capture the fate of art at the time of digital reproduction.

On the one hand, we can ‘google’ our way throughout the world without leaving our room; physicists can trigger atomic explosions without provoking radioactive fallout inside the computers churning out their simulations; millions of kids are able to play collective games inside huge arcades without buying any real estate. So, obviously, we should feel virtual wings growing on our back. Soon, no doubt, we will be ready to download our own ‘wetware’ body into the dry chips sustaining the World Wide Web.

But those dry pieces of silicone also have their flip side: every idea is now measurable in bytes; every piece of information has become traceable in numbers of ‘hits’ and ‘links’; for every connection you need to get a cable or to buy some ‘airport’ card; images now have a weight measured in so many Ks, and when they are too ‘heavy’ they ‘clog’ your mail accounts; formalism is incarnated in pixels, electrons and modems; computers heat up and, most distressing of all, they age quickly through a dizzying pace of planned obsolescence. In Plato’s time abstract ideas had neither bugs nor viruses, nor trademarks. Now, everything spiritual has melted into proprietary codes owned by Bill Gates or into machinery on which is written “Intel inside”.

So, is digitality the beginning of virtuality or the end of idealism? In a small but stunning exhibition called “n01se”, the artist Adam Lowe, and the historian of science Simon Schaffer, had already shown in 1999 that digitality had a long history beginning in the 16th century. It began with the invention of mezzotint, a new printing technique that allowed engravers to reproduce shades and shadows by multiplying dots alternatively black and white — the ancestors of our pixels. Not only is digitality an age-old technique, but as the philosopher of computing Brian Smith has shown, it’s not exactly true that modern computers are digital machines since their electric states remain analog. Digitality is an achievement of the collective organisational properties of computers not the intrinsic nature of their gates. Or, as Alan Turing himself said: “It is a convenient fiction that each switch must be definitely on or definitely off.”

The inherent analogue nature of the signals comes forward when you begin printing digital files, as Adam Lowe has done in another exhibition, using different printing techniques. Exactly the same file of 0s and 1s, once expressed in laser beams, bubbles or drops, generates images that look entirely different. So the formal machine might not be that formal after all. If digitality is a “convenient fiction”, it might explain why it is so hard to decide whether or not the information age leads us to a new virtuality or to a new materiality. With computers we are in for more than a few unexpected turns. Turing again says: “Machines take me by surprise with great frequency.”

It is this alternative definition of the digital age that has pushed Lowe to move from London to Madrid and to create there, with the Spanish painter Manuel Franquello, a studio called Factum-Arte devoted to the production of facsimiles. Their idea is not to produce a virtual replica of original works, but to use the digital files as a way to probe the material quality of the original works of art. The power of resolution of the 3-D scan is entirely devoted to directing an array of purpose-built copiers, printers and drillers that can reproduce a material copy. The digital file is not the end but the means to re-conquer materiality. In the studio, you need computers but also age-old skills like those of painters, engravers, moulders and sculptors.

Take for instance the copy Factum-Arte made of a portion of the tomb of the Pharaoh Seti I. The idea is not to produce a virtual presentation of the tomb: there is no screen, no goggle-eyed view good enough to pay justice to the precision of the scan. Neither is the goal to fool the visitor into a counterfeit version of the Valley of the Kings. Counterfeiting, as the whole history of fraud in art and science shows, does not require such great skills, since visitors’ minds are so easily fooled. No, the idea is to turn digitality upside down and to use the technical feat of printing a full-scale replica of a tomb in order to make clear why the texture of the original cannot be replicated.

Furthermore, and which is of great significance for conservation, why the original should not be touched by sloppy restorations. Every new drill, every new scan, every new colour printer, reveals in the studio another version of Seti’s inherent qualities: cracks, nuances of colours, stone granularity, varnishes, even the successive destructions and repairs. It’s as if the digital capture allowed peeling the original feature by feature, layer by layer, and all of that without touching it, except for the brief illumination by a tiny laser beam.

No, the digital world is not leading us toward the virtual existence of angels. (…) digital replicas are just as material as the originals, except they are more so.

In the end, so much care is taken in making the facsimile, so much energy, skill, invention, that what you get is a stunning second original, as precious as the first, and of course far more flexible! In the end, the digital replica not only possesses a precious aura but it increases the aura of the original by revealing its texture and by protecting it against wanton restoration. Closed to the public, the tomb of Seti may keep its secrets from future generations; opened to the public, restored more than once, it will have vanished without trace in a few decades.

No, the digital world is not leading us toward the virtual existence of angels. As Adie Klarpol, the young character of Richard Powers’ novel Plowing the Dark learns to her great distress, digital replicas are just as material as the originals, except they are more so. After having worked for several years on a perfect 3-D digital mock up of a work of art, she realises that the smart bombs aimed at Iraqi targets from the brand new digital battlefield somewhere in Florida use the same skills as the one she has been developing in her insulated laboratory. Suddenly, digitality inserts itself in the much longer history of facsimiles: “Thou shalt not make graven images.”